A Bloomsday conversation with Joyce scholar Kevin Birmingham, author of The Most Dangerous Book.

Many years ago, one of my closest friends and I were discussing the new rules of publishing. We played our respective roles: She, the successful editor, insisted that it was a numbers game. She might have tapped a pen. I, an English professor and poet, sputtered with romantic outrage. What about Thoreau, Dickinson, Kafka? What—and here I lowered my eyes and my voice—about Joyce?

Nope, my friend said. Wouldn’t sell.

Where controversial publishing is concerned, Kevin Birmingham’s The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce’s Ulysses (Penguin) offers an education for the realists and the idealists alike. Birmingham gives us a book that reads as part legal thriller and part narrative nonfiction, revealing that the modernist masterpiece provoked strong and sometimes unexpected reactions: Virginia Woolf refused to publish it. Ezra Pound defended it with the best force of his reputation, only to become its first censor. And Margaret Anderson, founder of The Little Review, the original magazine to publish Ulysses, stopped reading part-way through the novel, looked up and said, “This is the most beautiful thing we’ll ever have. We’ll print it if it’s the last effort of our lives.”

Of course, no one was more aware of the potential impact Ulysses might have on readers’ minds (and bodies) than the U.S. government. In honor of the June 16th celebration of Bloomsday, TBQ sat down with the author for an aerial view of the often-romanticized 1933 obscenity case, and ended up in a conversation that covered scandal to spirochetes to Snowden. With insight and good humor, Birmingham brings to life the many characters involved in the case and reveals that the book’s elaborate defense might just have been its most strategic promotion.

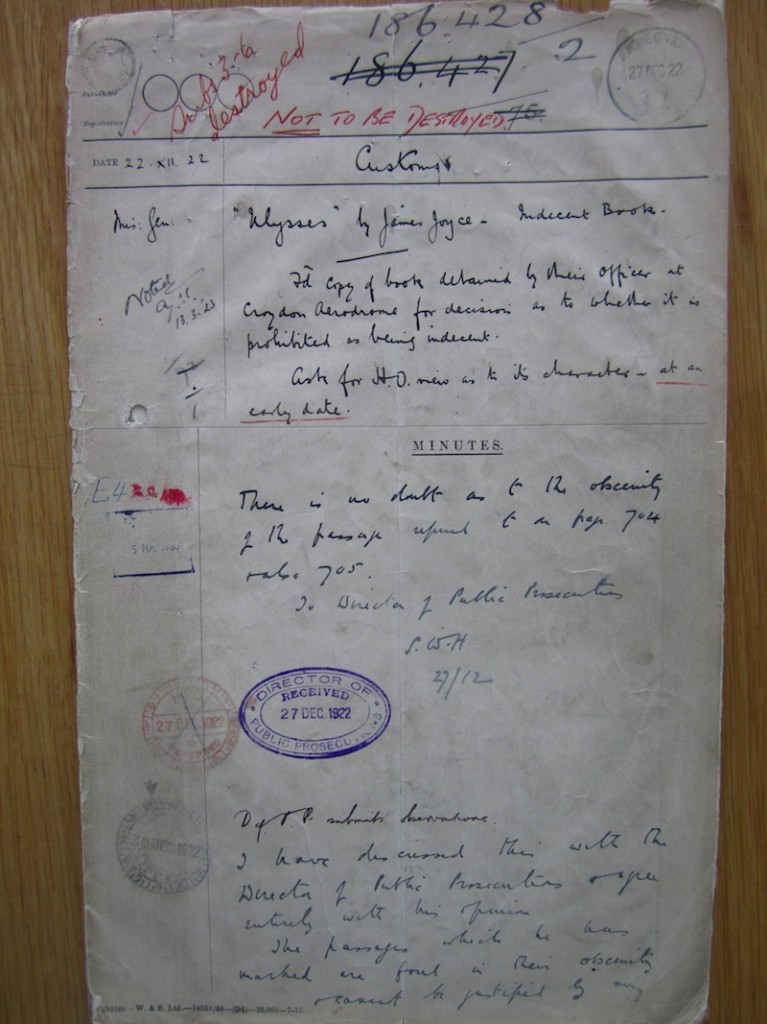

Kevin Birmingham: “This is the beginning of the Home Office file on Ulysses—the case was opened following a seizure of a copy of Ulysses at Croydon airport (“aerodrome”!) in December of 1922. You’re looking at Home Office officials talking to one another about what to do, and S.W. Harris, who was then the Undersecretary of State (later the Secretary of State) passes it off to the Director of Public Prosecutions, who functioned as the Crown’s chief legal prosecutor. You’ll notice at the top of the document that someone later marked in red ink, “NOT TO BE DESTROYED.” The first page is technically the second document in the file (186.428/2), and the submissions 3-6 were burned. We’ll never know why, but you find notices like this throughout the surviving documents. At some point (apparently in the 1960s) the British government destroyed dozens of documents in the Ulysses file.”

The Most Dangerous Book investigates so many urgent questions related to Joyce, Ulysses, and censorship. Still, it seems that much of your recent press coverage revolves around the book’s revelations about Joyce’s personal life, specifically the likelihood of his living with syphilis. Why do you think readers are so fascinated with the possibilities of his disease?

Well, I think Joyce doesn’t seem very human to most people. When you get the reputation for being a genius or a great author, the personal life seems to fade away, and a discovery like this makes him human. Another part of what’s fascinating is that he lived with this secret—an entire dimension of his life was hidden, and this is amazing partly because Joyce’s life has been so thoroughly examined. How could everyone have missed it for so long? It transforms the way we think of his day-to-day existence, and Joyce is nothing if not an artist of that kind of experience. So I don’t think curiosity about it is necessarily prurient.

Syphilis, like Lyme disease, is a spirochete, a corkscrew-shaped bacterium that can pass through almost any of the barriers of the body, including those that protect the central nervous system—ground zero for any artist. Have you observed any narrative or stylistic patterns in Joyce’s prose that correlate to the progression of his disease? How—if at all—did syphilis influence his craft or his creative process?

First I should say that Joyce didn’t have neurosyphilis—there’s no evidence that the bacteria infested his central nervous system. One of the telltale signs of neurosyphilis is something called locomotor ataxia, which gives people a debilitating, wobbly walk. There’s a brief home movie of Joyce in the 1930s, and he’s walking just fine. And while people have had fun joking that Finnegans Wake is the product of a rambling syphilitic mind, the truth is that if the spirochete got into his brain Joyce wouldn’t have been able to function at all by his late thirties.

Having said that, Joyce’s eye problems definitely altered his creative process. There’s one period in particular, in the middle of 1921, when Joyce had a serious bout of iritis in both eyes and was forced to stop writing for weeks just when he was trying to finish Ulysses. Joyce tended to think microscopically—he would add bits and pieces to Ulysses as if it were a jigsaw puzzle—and suddenly he just can’t work at all. So he’s lying in bed day after day for weeks, unable to see, and it forced him to imagine the book as a whole. As soon as he got better, he started requesting galleys for multiple chapters in order to bring out some overarching themes. He turned his blindness into an asset.

Mark Traynor, the manager of the James Joyce Centre in Dublin, asserted in the Guardian that it was the taboo of syphilis that kept people from discussing it. In The Most Dangerous Book, you argue that Ulysses “was dangerous because it demonstrated how a book could abolish secrecy’s power. It showed us that secrecy is the tool of doomed regimes.” Considering Joyce’s interest in challenging taboos and rewriting social codes, why would he have kept his disease a secret? Is there any evidence that Joyce himself judged his condition—that he associated the disease with a sort of moral shortcoming?

It’s impossible that he didn’t feel guilty about what was happening to him. Every time he suffered a new eye attack he had to accept the fact that at least one night in a brothel was the cause of it. Having said that, I’m not sure how, or if, it affected his understanding of morality. There’s a big difference between guilt and shame, and I don’t think he felt shame. But he did think of secrecy as tyranny, and I suspect that his own condition is what made him feel that tyranny so keenly. His books are in some ways confessional—he’s outing the secrets of daily life—and in his letters you can see him struggling to confess what was really happening to him. I think he wanted others to guess. His fiction sometimes does the same thing. He wanted people to lean in closer and find out the secrets for themselves.

What does your newly uncovered evidence of Joyce’s disease bring to our understanding of his work, Ulysses in particular?

I think this is the sort of question that can only be answered with further scholarship, and I hope my book helps generate that scholarship. Having said that, I think the basic facts of syphilis must have intensified what was already important to him about art: that tiny things can be devastating and life-changing. Joyce’s entire life was altered by microscopic organisms. It’s already Joycean, when you think about it. That you could have profound epiphanies, good or bad, from the tiniest things that most people overlook.

A person could devote his or her entire career to Joyce; in fact, some have. How did you approach your own research process?

I had this fantasy where I’d do all of the research up front and then start writing. I planned to have a happy and neat two-part process, but it didn’t work out that way at all. I spent a lot of time doing the basic legwork with the main figures of the story before shifting to the background work and then heading off to the archives. The blessing of this project is also one of the challenges: the archival record is incredibly rich, but that meant getting materials from about two dozen archives and sorting through all of it. And sometimes I just didn’t plan very well. I had to fly back to Austin because I didn’t get to all of the materials I wanted to see at the Humanities Research Center [at the University of Texas] there. I eventually started writing, but the research never stopped. Every turn in the story left me with new questions I needed to figure out.

Your research relied heavily on Joyce’s many letters. Did you note any interesting relationships between the prose style of Joyce’s letters and that of his creative work?

Joyce’s letters aren’t “Joycean” the way we typically think. Like almost anyone’s letters—especially someone who writes thousands of them—they’re different things at different times. Some of them are funny. Some of them are boring. The letters to Nora are remarkable, even beyond the so-called dirty letters. You could sense his helplessness when he started falling in love with her. He told her that she held him in her hand like a pebble — it would have surprised any of Joyce’s friends at the time since he had such a high self-regard and gave people the impression that he didn’t care about anyone’s opinion but his own. With Harriet Weaver, Joyce’s patron, he found a sympathetic listener, so he talked about his troubles constantly. She lived in London, so almost their entire friendship was based on this deep correspondence. Joyce didn’t have the neatest handwriting, but you get used to it. Most of them had bad handwriting, in fact. Except for Sylvia Beach—and she was very funny. I could read her letters all day without strain.

So it sounds like Joyce had a bit of a soft spot. That might seem surprising in an author who relies so much on explicit material, delivered fairly unapologetically. Do you believe Joyce himself considered Ulysses to be obscene? What I mean is this: Do you think he was defending the artistic legitimacy of so-called obscene material, or did he really not view Ulysses as obscene in the first place?

No, I don’t think he thought it was obscene. He knew he was crossing literary boundaries, but he didn’t think the boundaries were natural or even worth obeying. When he heard that one of his family members hid the copy of Ulysses he had sent to her because she insisted the book wasn’t fit to read, Joyce said, “If Ulysses isn’t fit to read, then life isn’t fit to live.” The point of obscenity is to mark off a category of experience as illegitimate—as not up for discussion—and Joyce wouldn’t have accepted that. Governments were already suspicious enterprises, as far as he was concerned, and the fact that they could fetter artistic production by labeling art and banning it was unconscionable.

If Joyce was already suspicious of government, then to what degree did he anticipate the legal battle over Ulysses? With the 1956 publication of Howl, for example, Allen Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti contacted the ACLU before copies of the poem reached U.S. Customs, to secure some protection from the obscenity trial they (rightly) predicted. Do Joyce’s letters reveal similar anxieties?

He certainly anticipated it. In fact, his response to the first obscenity verdict for Ulysses —a chapter serialized in a magazine in New York, The Little Review, when he was still writing the novel—was to make the book even dirtier. He didn’t play a big role in the legalization process, though, and even he might be surprised by how important the case has become. And speaking of the ACLU, the lawyer who defended Ulysses was one of the ACLU’s co-founders, Morris Ernst, but he had to work independently because the ACLU didn’t want to get involved with literary obscenity cases. Ernst was one of the only people at the time who thought that there was a First Amendment issue at stake.

How has the process of evaluating so-called “obscene” material evolved, legally, since the 1930s? With Ginsberg’s Howl, nine “literary experts” testified in defense of City Lights and Ferlinghetti. With Joyce, it seemed to be the judge himself who became the expert.

The Ulysses case technically wasn’t a trial. It was a hearing on two competing motions in which both sides agreed to forego a jury. One of the things that makes the Ulysses case unusual is that the government was relatively cooperative (this changed during the Circuit Court appeal). Morris Ernst wanted to put the case directly before a judge because, in his experience, juries were much more likely than judges to deem a book obscene. There was something about deliberating in front of 11 other people that made everyone easily scandalized.

Ernst’s ingenious move was that instead of having experts testify at a trial, he had Joyce’s assistant tape copies of expert opinion inside the covers of the copy the government seized. That way he could still have his experts but get rid of the jury.

The Most Dangerous Book emphasizes the significance of both the Comstock Act, which criminalized the mailing of “obscene, lewd, or lascivious” material, with the US Postal Service doing much of the enforcing, and the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, the moral nannies who had so much sway that most publishers opted to meet their standards even before submitting texts for review. You refer to these actions of the USPS and the NYSSV as “moral surveillance.” Are there any contemporary equivalents, in your opinion?

Most literary censorship takes place in public schools and libraries. The big difference is that school boards and private interest groups have taken the place of the state and federal governments. These days, moral surveillance gets folded into political surveillance so that we justify the prosecution or harassment of someone (a “terrorist” or a “traitor”) by calling it a violation of public safety. This was exactly the same reason for justifying anti-obscenity laws. Lawmakers insisted that they had to ban texts, information and speech in order to maintain public order. In fact—and I only mention this briefly in the book, because it can get complicated—it seems as if the principles guiding the identification of treasonous texts were based on obscenity law, which had a more recent and rich case history when the Espionage Act was passed in 1917.

So is it safe to assume that Joyce would have defended Edward Snowden?

Oh, definitely. There’s one point in Ulysses where Stephen thinks of secrets as “tyrants willing to be dethroned,” and it’s reasonable to think of Stephen as a mouthpiece for Joyce in this instance. Joyce was keenly aware of the tyranny of secrecy—partly because of his secret suffering with syphilis and partly because censorship and the entire legal category of “obscenity” are manifestations of that tyranny—but the real Joycean insight is that secrets will always come out, that they even want to come out. If it wasn’t Snowden, it would have been someone else. The NSA and the people who will inevitably bring it down (whether in five years or five hundred) are equally a part of the nightmare of history.

Beyond that, Joyce declared himself an anarchist in his mid-twenties, and his antipathy toward all government remained with him his entire life. He thought all government power tended to be abusive, and the NSA is an astonishing example of that abuse.

So much of Ulysses seems to react against something: social restriction, legal limitation, the hypocrisy of decorum. What, if anything, does the book promote? Regardless of what is or isn’t reasonably considered “obscene,” what does Joyce offer as sacred in the book?

Joyce wouldn’t have subscribed to anything being “sacred.” The whole category is another version of “authority,” and Joyce rejected that as a phantasm. I should say, though, that I don’t think Ulysses is any more reactionary than any other new work of art. In fact, it seems to try to engulf everything—all styles and discourses have their place in modernism’s epic. So, for example, Gerty MacDowell’s consciousness is shaped by the magazines and pulpy romance novels she reads, but that chapter doesn’t react against that type of writing. Joyce uses it, turns it around, and shows us qualities to that writing that we never would have seen before. Modernists like Joyce were certainly opposed to empire and aggressive empiricism and Victorian sensibilities, but the response, at least in Joyce’s case, was far more complex than reaction.

That’s a useful clarification. It makes me wonder, though: The book rejects authority and strives to be inclusive—to be thorough—in a way that accurately renders the complexities of human psychology and of social interactions. How would you say these interests are served by Joyce’s narrative and stylistic innovations? In a way, even the tradition of narrative itself, with its expectations for beginning, middle, and end, suggests a simplicity and an objectivity that seem out of sync with Joyce’s view of the world.

I agree. The first thing writers are told to do is to develop a distinctive voice, and having a consistent style throughout a book is one of the ways narrators and narratives assert their authority. Ulysses fractures all of that. We could think of it as a narrative version of cubism, where we see an object from multiple perspectives at once, but I wonder if it’s more fundamental than that. Are we, as people, stylistically consistent? With the way we live? Or even the way we think? I suspect we like to think of our lives and our thoughts as being seamless, but Joyce’s insight is that our experience of the world is more like a pastiche, particularly in the modern urban spaces—it’s a telling coincidence that a poem like Eliot’s “The Waste Land” would come out the same year as Ulysses. Maybe the fantasy of our own seamless consistency is the most tyrannical authority.

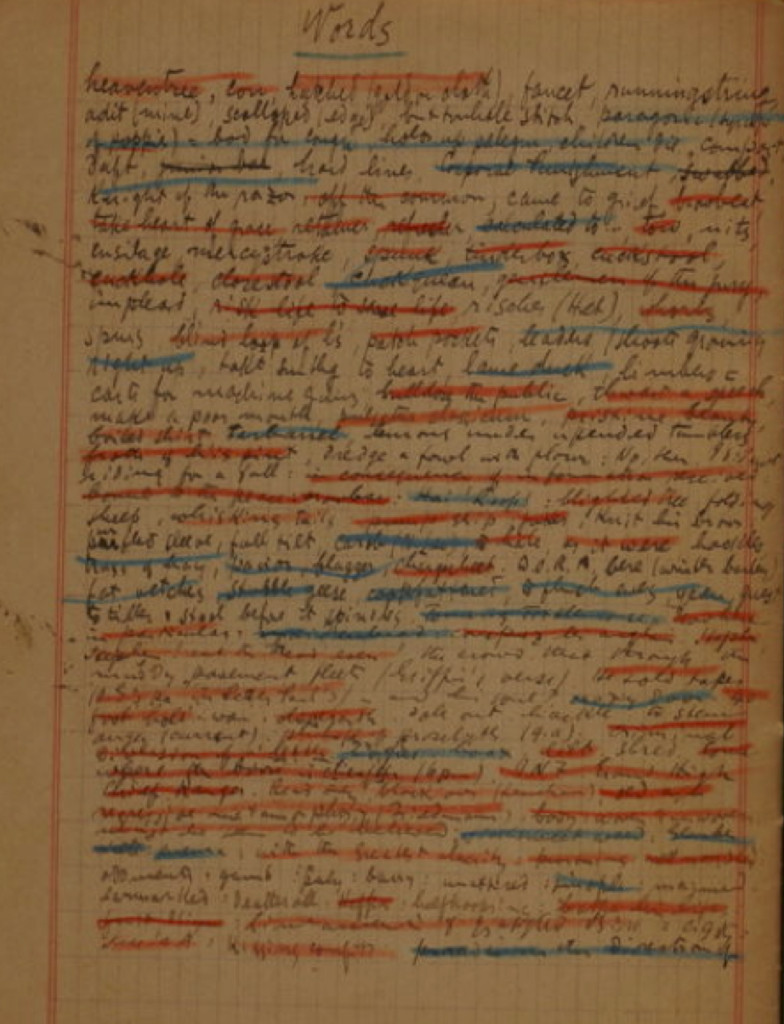

Kevin Birmingham: “Joyce kept notebooks filled simply with words and phrases that he knew he wanted to insert at various (seemingly precise) places in the text. I’ve included one page entitled “Words.” When he used a word, he’d cross it out with a crayon. So, for example, “heaventree” is the first word on the page, and he crossed it out when he inserted it into the “Ithaca” episode.” (National Library of Ireland)

Of course, Eliot shared a friend and editor with Joyce: Ezra Pound, a father of modernism and one of Joyce’s most loyal supporters. Yet The Most Dangerous Book notes that it was Pound who censored Ulysses before anyone else. Of course, Pound justified his strikes as friendly edits—edits that just happened to remove the most explicit references in that installation. He criticized Joyce’s prose for its “needless superlatives,” claiming they gave the effect of “bad art.” Did Pound have a point? Did Joyce’s vision for the novel risk overwhelming his concerns about craft?

There was nothing “superlative” about what Pound cut. He was trying to pacify John Quinn, who was funding The Little Review and whom Pound was cultivating as a patron for himself and his friends. Quinn was hot-tempered and had very little patience for anything that might provoke the authorities. Quinn suspected that it would be his job to come to Joyce’s rescue if The Little Review were ever prosecuted, and, of course, Quinn was right. Pound was usually relentless when it came to literary integrity, but he knew how to yield a bit at crucial moments—at least in those early years.

It’s true, though, that many of the early reviewers worried that Joyce was a promising writer who had lost control over his own talent. You can imagine how the novel would seem reckless to those first readers. It took a while, but the profound craftsmanship eventually became clear to those who were willing to be patient with the book. It’s amazing, in retrospect, that Pound didn’t raise more objections as the portions of the novel made their way to him bit by bit. He thought Joyce had gone off the deep end in the third episode but changed his mind after a few weeks. That’s usually the way it was with people—including Virginia Woolf, one of the mothers of modernism. You’d read it and possibly hate it. But it would stick with you somehow, and the brilliance would shine through. It works on the mind slowly.

The Most Dangerous Book animates Joyce’s extensive network of supporters—lawyers, heiresses, publishers, artists—who helped to publish and to distribute Ulysses often at great risk to their finances, to their reputations, and in some cases to their personal freedom. At least one publisher stated an urgent need to publish Ulysses, even if it meant the collapse of his publishing house. What do you think Joyce would say about contemporary publishing?

In a lot of ways publishing hasn’t changed very much over the last 90 years. Houses still run on razor-thin profit margins, and despite all of the sophisticated marketing tools, it doesn’t seem as if anyone’s any better at predicting which books will sell and which ones won’t. All of this makes publishers risk-averse and generally unwilling to experiment. It’s difficult to imagine Ulysses finding a publisher today, and it’s heartbreaking to think of all the great experimental novels that never got published and are now moldering in erstwhile writers’ closets. Joyce was an exceptional writer, but he was also lucky enough to have had a few avid, well-placed supporters. He was stubborn as hell and he worked incessantly. That’s probably what it always takes to get published.

Optimists might say that we are awash in great contemporary literature. But I can’t imagine someone reading The Most Dangerous Book without feeling compelled to revisit—or to begin, or, finally, to finish—Ulysses itself. Why do you believe it’s so important for readers to read the book now?

I think for the same reasons that any excellent book never gets old. It says something about who we are as human beings. You can’t read Ulysses without becoming aware of what your own thoughts are like, or how we tell stories to one another, or how cycles of history keep repeating themselves, or about what it’s like to look up at the galaxy and see the dark fruit of the spaces between the stars hanging down. Every generation brings new concerns to a book, I suppose, and maybe our concerns are about privacy and connectedness. Ulysses breaks down barriers between the private life and the public life, the interior and the exterior, and that’s something we feel more and more these days, whether because of the NSA or Twitter. So today’s readers can engage that public-private existence in a way that previous generations couldn’t. Maybe one day we’ll find that the novel is best suited for the 22nd century. We’ll have to wait and see.

One last question: what can readers expect from you next?

I’ve started working on a book about Dostoevsky for Penguin Press. I’ve wanted to write about him for a long time because he’s had such an incredible life and because the relationship between his life and his writing is so intense, like Joyce’s, but I couldn’t find a compelling angle until recently. I don’t want to get into it too much because it’s still very new, but I’ll say there’s nothing like starting a new book to help you get over the end of the first one.

•

Kevin Birmingham received his PhD in English from Harvard, where he is a lecturer in History & Literature and an instructor in the university’s writing program. His research focuses on twentieth-century fiction and culture, literary obscenity and the avant-garde. He was a bartender in a Dublin pub featured in Ulysses for one day before he was unceremoniously fired. This is his first book. He is currently working on a second book forthcoming with Penguin Press.

Kevin Birmingham received his PhD in English from Harvard, where he is a lecturer in History & Literature and an instructor in the university’s writing program. His research focuses on twentieth-century fiction and culture, literary obscenity and the avant-garde. He was a bartender in a Dublin pub featured in Ulysses for one day before he was unceremoniously fired. This is his first book. He is currently working on a second book forthcoming with Penguin Press.

Allison Adair is a poet and a Contributing Editor for The Brooklyn Quarterly. She teaches at Boston College and Grub Street and holds an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

One thought on “Free Ulysses!”