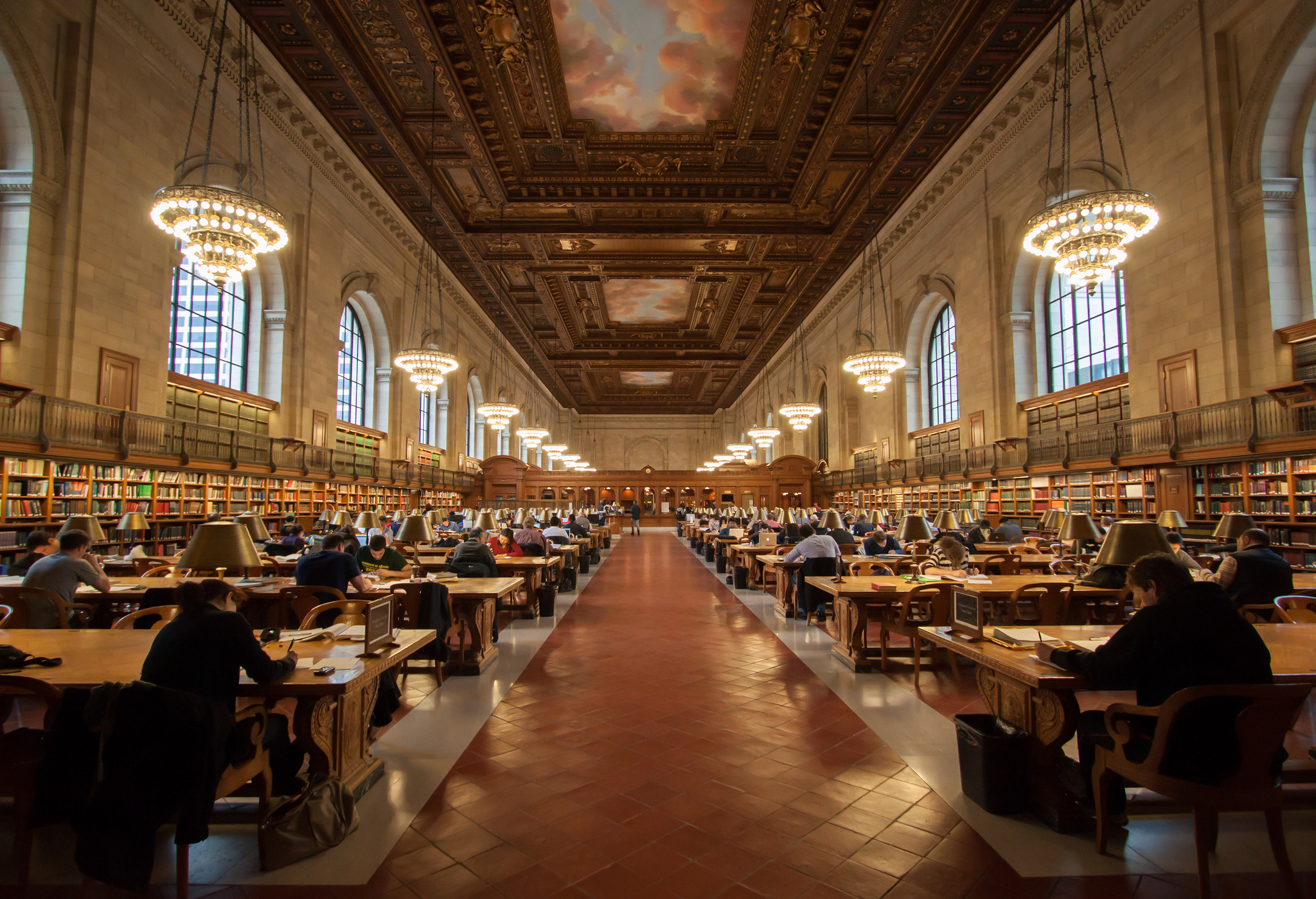

Image: Victoria Pickering/Flickr

Margaret Fuller—a journalist, critic, and feminist scholar—wrote powerfully in her most enduring work, Woman in the Nineteenth Century (1845), of the political need and moral imperative to grant women equal access to education. Her intent was less to argue that women should have the right to knowledge in order to fulfill a particular social purpose and more to assert that without rights to education—imparted by institutions and enforced by revised social norms—women could not assert their political rights as citizens in the public sphere.

It’s fitting that we use Fuller to open our latest editors’ note because in addition to her other talents she was also an editor, for Ralph Waldo Emerson’s transcendentalist journal The Dial. Though purportedly the best-read person of her time in New England—male or female—Fuller also endorsed a program of learning through discussion and debate. Through participating in conversations about great questions facing the world, Fuller believed women could find their own voices despite having limited access to libraries and institutions of higher learning.

We’ve come a long way since 1845, to be sure. Women now outnumber men in multiple learning disciplines and more women than men enter America’s colleges. But Fuller’s “conversationalist” approach to women’s education—the centrality of dialogue and civic engagement with great issues of the day—mirrors our intention with this issue devoted to education and the public sphere. Our mission endorses the power of narrative and the critical importance of public intellectual work. In this we include not only the journalistic work done by scholar-activists or by cultural critics but also the labor and production of knowledge by those actively engaged in solving public problems or enriching public life. Implicit in this category is an investment in education and the public sphere, an area of inquiry the pieces in this issue situate explicitly as congruent with an active commitment to storytelling as a method of social transformation.

In an issue devoted to stories about education, these contributors have prioritized the experiences of people above the analysis of policy or current debates about pedagogy. Many publications and policy experts are rightly delving into both and we do not wish to dismiss or replicate their efforts. Rather, what you will find here, in genres ranging from poetry to interview, are the fieldnotes of teachers, journalists, artists, scholars, and critics exploring education as a core precept of civic engagement.

The pieces in this issue place front and center what Fuller might have called the “great questions” of our moment. How does or should education address social issues, enable us to be civic and social innovators? Who and what are the most productive drivers of education as a force for public good? What are the most creative ways of using education to enrich the public sphere, especially in less visible communities across our country? How do people learn (or continue to learn) to build communities once they’ve entered the working world? In what ways can education foster the development of better, more involved citizens?

To ask these questions at all requires that we acknowledge the increasingly rocky and treacherous terrain students and educators alike are navigating. Rudy Fichtenbaum of the American Association of University Professors makes this point in his essay, as does Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung’s Ethan Earle, who outlines how we are currently failing the students who comprise what he calls the “debt generation.” “Almost 60% of student debt is held by families whose total net worth is less than $8,500,” Earle writes, and “the fight against the student debt crisis is indeed a fight to save a generation.” Reporter Sarah Kendzior analyzes how Sesame Street’s move to HBO spotlights future generations of children left behind as our systems of education—like our world in general—grow increasingly connected and increasingly unequal. “Today 30 percent of Americans have no broadband internet and 16 percent have no Internet at all,” she marvels. “Thirty-seven percent of Americans without a high school diploma remain unconnected. At my daughter’s St. Louis-area public school, where most children receive free lunch, announcements are distributed only on paper because so many families lack internet access. These kids are not exceptional, just invisible.”

Several contributors to this issue probe how to make invisible communities and unarticulated ideas more a part of the public discussion about education. Each in their own way, these writers argue in favor of re-framing the conversation. By using a different lens on the scope and impact of higher education, they contend, blurred corners are thrown into sharper and more visible relief. Daniel Choi examines the “hidden curriculum” that is “embedded in every aspect of the college student’s life,” while Jonathan Giuffrida refreshes the now-common debates over the value of STEM versus the humanities by interjecting forgotten histories of the liberal arts as a way of creating intellectual exchanges, rather than silos of knowledge. Kristin Oakley offers up personal reflections on being a first-generation college student and young professional grappling with senses of difference—social class and educational background—that recede in visibility to others as she travels from leafy campus to urban metropolis. “My life in New York City is the one I’ve chosen to live,” she writes, “but still I don’t always feel it’s mine.”

In a conversation with TBQ contributing editor Rob Goodman, The Future Project co-founder Kanya Balakrishna details her organization’s quest to embed Dream Directors in public schools in major cities to help expand their definitions of success. These Dream Directors help students with “the business of life and of growing up and of figuring out how to live a life in which you feel fully alive and fully expressed.” The Future Project challenges the categories of what “education reform” can be. Just as vociferously, award-winning polymath Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts challenges the boundaries of gender, genre, language, and motherhood. Nelson talks with Jennifer Doerr about the dueling urges to classify versus transcend, the willingness to risk being unliked in the service of truth-telling, and the strange new ground of writing about family happiness.

Sometimes the most creative ways to use education begin in your own backyard—a neighborhood effort that works its way into the classroom from the performance space or computer screen. Katy Reckdahl reports from New Orleans a decade post-Katrina about how Dancing Grounds, a DIY dance studio in the upper 9th Ward, is part of a developing arts education node that is helping to regenerate the city. Stefan Kielbasiewicz explores a charter school in the Fruitvale neighborhood of Oakland that is using gamification to enhance the experience of education.

The issue also brings new poetry from Susan A. Roberts and a selection of verse from poet Robin Beth Schaer’s acclaimed collection Shipbreaking. Plus, fiction from Morgan Beatty and a round-up of criticism reviewing recent titles that represent or re-frame scenes of education. Keija Parssinen, author of the novel The Unraveling of Mercy Louis, describes Julie Schumacher’s Thurber Prize-winning novel Dear Committee Members as a satire where the joke’s on us. Alison Hart reviews Leah Hager Cohen’s latest novel, No Book But the World, “a meditation on education—particularly, a child’s path out of the fog of innocence.” In her review of Ander Monson’s genre-bending Letter to a Future Lover: Errata, Secrets, Inscriptions, and Other Ephemera Found in Libraries, Naomi Skwarna deduces a “labyrinth in miniature,” in whose best moments “the book is less a receptacle for marginalia than it is a mirror, used to reflect the past and the future (the future lover).”

The pieces in this issue do not presume to offer a comprehensive answer to any of the “great questions” posed by contemporary challenges and confrontations concerning education and the public sphere. Rather, they insist on an attentive sifting through the stories of people and places where that work is taking place—in communities or between the pages of a book. The story itself, in the telling and in the learning, holds power. Likewise when asked what vocation education should enable women to take up, Margaret Fuller concluded at the end of Woman in the Nineteenth Century: “But if you ask me what office they [women] may fill; I reply—any. I do not care what case you put: let them be sea-captains, if you will.”

The people and places chronicled in this issue are but a selection of ships being steered in the direction of social engagement, of civic innovation, of productive critique, and—we believe—ultimately in the direction of progress. As you read, we hope you keep company with them a while as they sail just a little further forward into the future.

In this issue

Essays and Journalism

Daniel Choi, The Hidden University Curriculum

Ethan Earle, Saving the Debt Generation

Rudy Fichtenbaum, Who’s Teaching University Classes—and Why It Matters

Jonathan Giuffrida, Valuing the Liberal Arts

Sarah Kendzior, Generations Left Behind

Stefan Kielbasiewicz, Turning Fruitvale’s Students Into Heroes

Kristin Oakley, What Social Class and Education Mean To Me

Katy Reckdahl, Get In Where You Fit In

Poetry

Susan A. Roberts, Three Poems

Robin Beth Schaer, selected poems from Shipbreaking

Interviews

The Future Is Their Project: Rob Goodman interviews Kanya Balakrishna

“Making Space Around the Beloved”: Jennifer Doerr interviews Maggie Nelson

Fiction

Morgan Beatty, Only Babies Who Are Happy

Reviews

Alison Hart on Leah Hager Cohen’s No Book But the World

Naomi Skwarna on Letter to a Future Lover

Keija Parssinen on Julie Schumacher’s Dear Committee Members