One of the things we do as archivists is describe documents. We’re careful when we describe, because we know that description can easily become prescription. The labels we give are what allow people to find documents in our archives, but they can also become authoritative, definitive. Letters, memos, drafts of novels, notebooks, posters—text documents like these have the benefit of being always readable, in some sense, simplifying the task of description. But how does one accurately read or describe an object?

The archives in the Downtown Collection at NYU’s Fales Library and Special Collections, where I am Senior Archivist, are filled with objects. The collection documents New York’s Downtown art scene of the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s, comprising the papers of postmodern dancers, experimental playwrights, photographers, zinesters, poets, and No Wave filmmakers. We house the archives of art collectives, activist groups, and artist-run spaces. Since Downtown art practices were so multi-disciplinary (everyone tried everything, and everyone was in a band), we’ve had to adopt a broad view of what a document is. We preserve functional objects like sets, backdrops, props. But our holdings also include objects whose “functions” are less clear: the Outpunk “queer skateboard,” hundreds of (mostly pit-stained) t-shirts, and the eyeglasses of several men who died young during the AIDS epidemic.

The archive of artist, writer, and AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz (and yes, he was also in a band) is one of our richest: it contains his journals, letters, contact sheets, and taped voicemails, as well as hundreds of objects, ranging from the mundane to the talismanic. One of the largest is a papier-mâché head in the shape of a toothy wolf or dog, with a vivid red, wide-open mouth. It’s fragile and awkward to store, and the notorious instability of newsprint means it’s impossible to preserve for the long-term, but it’s an object we show often to the classes that pass through Fales. We call it “the wolf’s head.” This wolf’s head is, in fact, both an object and a text—its surface is covered in newspaper clippings from articles about the AIDS epidemic.

When I started working at Fales seven years ago, I didn’t know much about the history of the wolf’s head or why David had made it. In 2010, when the National Portrait Gallery caved in to the religious right and removed David from their show “Hide and Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture” (because of eleven seconds of ants crawling on a crucifix), our research to trace the origins of that footage led us to Silence = Death, a film by Rosa von Praunheim and Phil Zwickler about artists living with AIDS. Halfway through the film, before his montage from Fire in my Belly, David reads from one of his much-repurposed texts (it reappears in his artwork Untitled for ACT UP in 1991):

“If I had a dollar to spend for healthcare I’d rather spend it on a baby or innocent person with some defect or illness not of their own responsibility; not some person with AIDS…” says the Texas healthcare official and I can’t even remember what he looks like because I reached in through the TV screen and ripped his face in half I was told I have ARC recently and this was after watching seven friends die in the last two years slow vicious unnecessary deaths because fags and dykes and drug addicts are expendable in this country “If you want to stop AIDS shoot the queers” says the ex-governor of Texas…

He’s wearing a homemade white t-shirt that reads FUCK ME SAFE, and he’s standing against a brightly lit red background. The footage is intercut with images of a wolf figure—someone wearing our wolf’s head, and a fringed newspaper body suit—lunging at David as he fights off the attack with a flamethrower.

David is mainly known as an urban figure, an icon of the East Village and Lower East Side, but animals and nature were deeply meaningful to him. He spent a lot of his time as a kid playing in the forests and ponds at the edges of New Jersey’s encroaching suburbs. Certain animals appear regularly in his artwork (and throughout his archive): snakes, ants, monkeys, dogs, wolves. David loved any aspect of nature that was uncontrollable, reminders that “the future of civilization and all its leanings could suddenly be altered or whisked from human hands by natural occurrences or ‘unnatural’ phenomena.” But some animals, like ants, represented the human world of imposed order. Wolves and dogs could serve both functions in his work, from what I’ve seen. He wrote about his identification with “wolf boys,” lost children raised in nature, free of culture. But wolves and dogs are also pack animals, moving within a strict hierarchy—much like the human inhabitants of what David referred to as the “One-Tribe nation”.

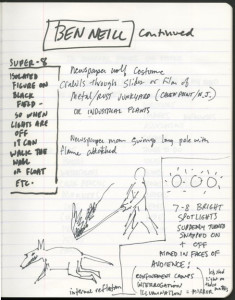

Recently, I found a sketch (see above) of our wolf’s head and the flamethrower in one of David’s 1989 notebooks; the handwritten notes he made suggest it was used in a performance he did with Ben Neill, In the Shadow of Forward Motion (ITSOFOMO). In typed notes for ITSOFOMO that I found in the archive, David writes about the role of the wolf:

Person in MEDIA WOLF costume zig-zags out of the darkness into light as blank politician gesticulates above…. FIGURE WITH BLAZING TORCH swinging in wide arc back n forth causes MEDIA WOLF to retreat (media wolf is made of newspaper headlines).

Was the wolf originally made for this performance, then? I’m not sure. It seems clear it represents the way the media and the “One-Tribe nation” colluded to obscure the AIDS crisis. But ultimately—although I can now more accurately describe this object as the “Media Wolf” —it’s not for me, as an archivist, to say what its meaning or function are. Perhaps this object will always remain, to a degree, unreadable. But does it remain without meaning? You’re welcome to come look and decide for yourself.

This essay is one of a series in this issue that addresses the role of archives in documenting conflict, culture, and history-in-the-making. You can read further essays from WITNESS senior archivist Yvonne Ng here and documentary filmmaker Katy Chevigny here.

•

Lisa Darms is a writer and archivist living in Manhattan. As senior archivist at NYU’s Fales Library & Special Collections, she manages the Downtown Collection, which documents downtown New York’s art, literary, and performance scenes from the late 1960s through the 1980s. She is also the founder and curator of the Fales Riot Grrrl Collection.

Lisa Darms is a writer and archivist living in Manhattan. As senior archivist at NYU’s Fales Library & Special Collections, she manages the Downtown Collection, which documents downtown New York’s art, literary, and performance scenes from the late 1960s through the 1980s. She is also the founder and curator of the Fales Riot Grrrl Collection.