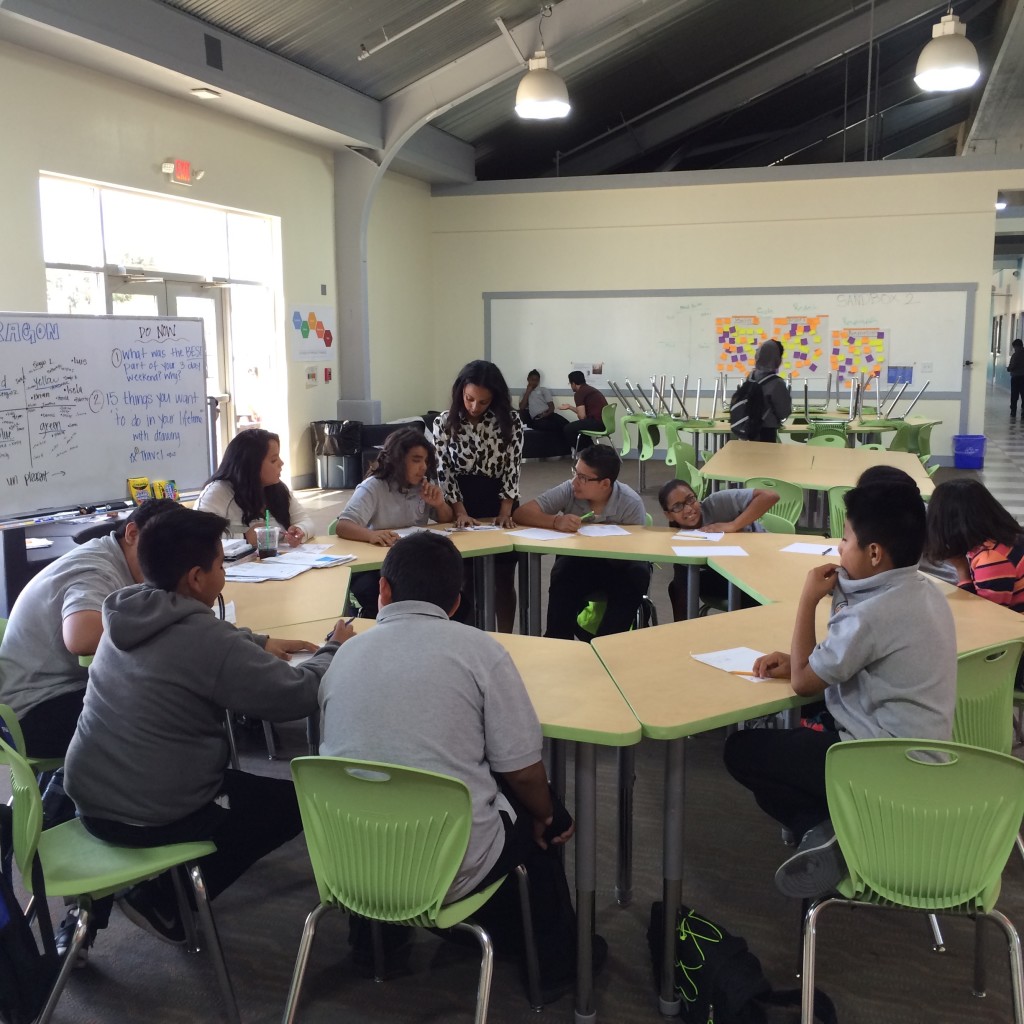

Inside a classroom at Epic. Image: Stefan Kielbasiewicz

When I exit the Fruitvale BART station on my very first visit to the East Bay, I’m surprised to find a colorful plaza called Fruitvale Village with an outdoor market featuring fresh fruit and vegetable stalls, handcrafted jewelry, and a stylish café serving beignets. I’m here to learn about Epic, a recently minted charter school with enormous ambitions: not just to improve the quality of education in Oakland’s lowest-income neighborhood, but to radically change students’ perception about learning and how they can improve their community. After walking just one block towards the middle school, the topography suddenly begins to reinforce my initial preconceptions of Fruitvale. On one side of the school’s unassuming exterior runs a freight train track; on the other side lies an abandoned lot in front of the elevated BART track. This in turn hangs over a busy road lined with dilapidated houses and chain-link fences.

By the time I reach the school gates just a half a mile from where I started, my clothes stick to my skin from the dry, ninety degree heat. There is little shade to be found, except under a few towering billboards. Inside Epic’s white, barrack-shaped building, however, is an oasis — cool, quiet, spacious, and still empty of children before classes begin in late August. Francis Abbatantuono, Epic’s Director of Personalized Learning, and Ruth Negash, the Assistant Principal, have invited me to talk with them and their colleagues about their plans for the school’s second year of operations. On a conceptual level, it comes down to this: by the end of the three years between grades six through eight, Epic wants to turn its students into heroes.

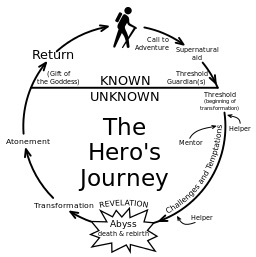

Inspired by the anthropologist Joseph Campbell’s idea of the Hero’s Journey, Principal Michael Hatcher, Abbatantuono, and Epic’s entire faculty want their students to embark on their own heroic journey: to become masters of their own learning and development through the school’s curriculum. The language and imagery is not coincidental — most of Epic’s students mirror the backstories of many superheroes, coming from modest backgrounds. Low-income Latino families make up eighty percent of Fruitvale’s population, and less then half of Oakland’s black and Latino male students end up graduating from high school. While there are already numerous charter schools in the area trying to provide an alternative to public schools, with inspirational names such as Arise, Ascend, Achieve, and Aspire, Epic believes that actively engaging students with their experience of growing up in Fruitvale will help them develop as individuals.

Epic’s leadership worries about the characteristics that influence youth in many low-income communities, such as gang involvement, violence, and academic underachievement. “Right around middle school, kids start to question who they are as a person,” Principal Hatcher explains to me. “A lot of times, schools leave that narrative construction to what happens outside the gates. If we could intercept that and give kids a schema to see themselves as heroes—that could counter certain narratives.”

Epic was originally conceived around the idea of marrying a STEM education with a grassroots, community-based focus. The STEM model, which applies the disciplines of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics to real-world problems, is particularly popular among charter schools that not only want students to draw connections between educational material and their ordinary lives, but to be better equipped for future educational and career prospects.

But before he became an educator, Hatcher initially wanted to be a game designer. For him, the worlds of gaming and education seemed to fit hand-in-glove. And so, in 2013, despite the school’s original plan, Hatcher and his colleagues went to the Startup Weekend: Next-Gen Schools competition in San Francisco to propose a gamified and quest-based curriculum in order to attract substantial awareness and approval from the educational community. They won.

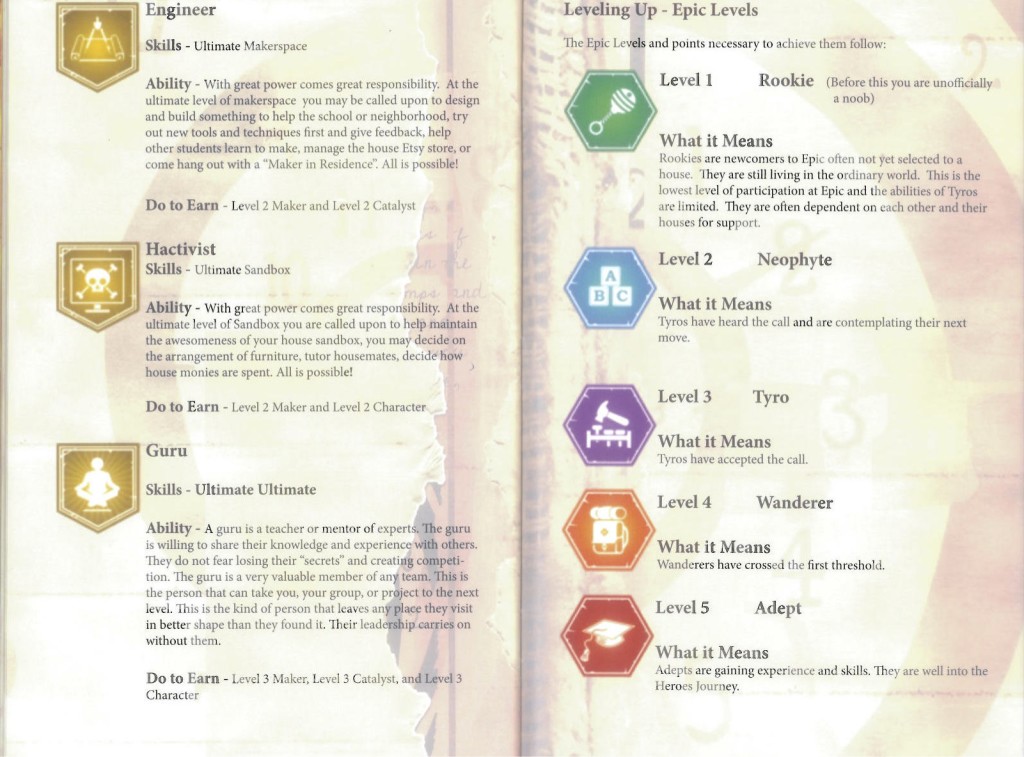

Gamification, which involves applying video game and role-playing features to ordinary environments, is typically used to increase user engagement in marketing, but is now becoming a popular idea in curriculum design. At Epic, rather than receiving traditional grades, students are assessed by the accumulation of points, which allow them to progress to the next grade. Students can “level-up” and unlock certain privileges, such as going to the bathroom without a hall pass, listening to music on their school-provided Chromebook laptops, and using cell phones in designated areas known as sandboxes.

The four sandboxes are large, open common rooms leading both outside and connected to classrooms through a long corridor, and are one of the distinguishing features of the school. All of Epic’s current 317 students, thirteen teachers, and eight guides (another unique feature of the school) are divided into four houses: Icon, Paladin, Paragon, and Meta, and leagues: Aeris, Aquas, Incendium, and Terra. Each house is tied to a sandbox, where the houses’ huge, regal banners hang on the walls and various notes and quotes by the house’s students are written on the whiteboard. Leagues, meanwhile, determine how students from different houses mix in classrooms; between classes these leagues, led by a teacher, walk in single-file to their next classroom.

During class periods, students work in small groups under the instruction of a teacher; during “flex” periods, students work in their sandboxes on individual tasks according to their personal schedules. By eighth grade, students will spend most of their time in the sandbox, deciding what assignments they need to work on and when. The Hero’s Journey model is designed to allow students to develop according to their own pace and abilities.

Gamified schools exist elsewhere in the United States. Quest to Learn in Chicago and New York, for instance, employs elements of game design in its curriculum, and its students play games as well as make them. Students at Playmaker in Santa Monica, California play games in virtual and physical environments, design objects in workshops, and use games to pursue individual academic interests.

But Hatcher is quick to differentiate himself from other gamified schools. “They use games; we are a game,” he states. The educational models of these schools may not be as different as Hatcher suggests. But what does differentiate Epic from seemingly similar schools is that at Epic, gamification is enmeshed with the school’s focus on the surrounding community.

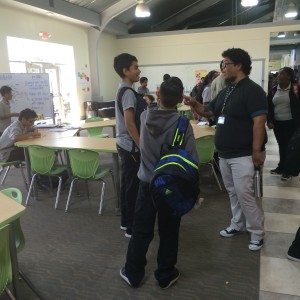

Perhaps no one is in a better position to navigate the nuances of all the games at play at Epic than the guides, who may be the most innovative feature of the school. Originally included in the first STEM model for the school, guides fall somewhere between teachers’ assistants and guidance counselors, but they’re really more like mentors who guide students on their personal journeys. Their domain is predominantly in the sandboxes, and their job is to motivate students to keep on track with their individual learning. They’re also available for students to talk to if they’re having any issues at school or at home. Most of Epic’s teachers agree that the school’s success or failure really rests on guides’ shoulders. There are eight guides in total, and each has about forty students under his or her wing throughout the student’s entire three years.

Christian Martínez, a Lead Guide, greets students on registration day while they have their I.D. photos taken. Martínez, like most of the guides, belongs to the Fruitvale community. He came to the United States from Mexico at the age of ten as an undocumented immigrant, and encountered his greatest challenges during adolescence.

“While I was in high school I lost one of my parents, I faced gun violence and was shot in the right knee,” Martínez recounts. “I guess that’s kind of where my quest started to take place.”

Faced with the all-too-common predicament of whether to go to college or work, he decided find a job and go into “survival mode”— working in positions such as a janitor or a custodian before acquiring a job in public education.

Most of Epic’s guides are in their mid to late twenties and aren’t certified in education. Unlike the parachuting transplants of organizations like Teach For America, guides are part of the Oakland community and have overcome challenges in their pursuit of education, which can help them relate to students. “The culture we have built with them is not really like a teacher, but like a family member,” Martínez says.

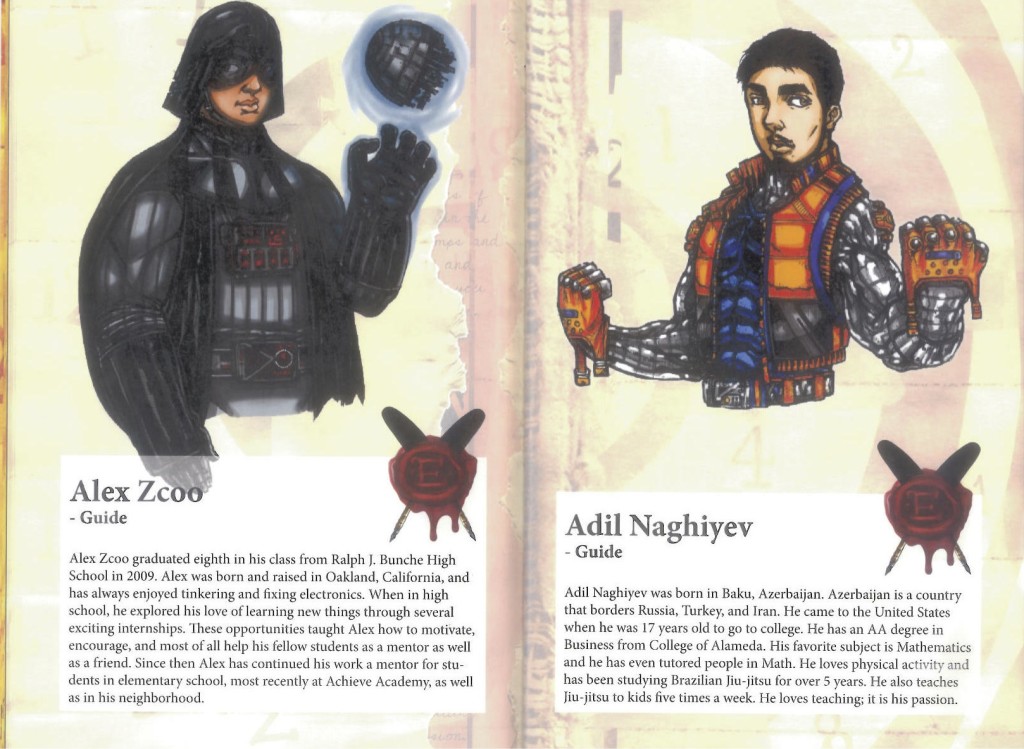

Since most of the guides have grown up in Fruitvale and have gone through their own struggles, they understand the landscape. Like Martínez, Alex Zcoo had serious difficulties in high school, but was eventually able to graduate, mostly by teaching himself. Another guide, Adil Naghiyev, emigrated from Azerbaijan to Oakland at the age of fifteen and was recruited to work at Epic by Abbantantuono, whose children attended Naghiyev’s Jiu-Jitsu classes. Mr. Christian, Mr. Alex, and Mr. Adil, as their students know them, have the time, patience and interest to help those who might be experiencing similar difficulties to the ones they faced.

“We not only talk about what happens in school, but what happens outside as well,” stresses Martínez. “When I was in school nobody addressed that—it was the big elephant in the room. But what’s happening outside impacts more than what happens inside, and once the schools are doing better, the city will do better too.”

Last year, Martínez took this a step further, implementing a “home visit” initiative that involves guides visiting the homes of students twice a year to talk to parents who typically don’t have the time or energy to keep tabs on their child’s education. However, guides often visit homes more than twice, and sometimes on weekends or late at night if there is particular cause for concern. Nearly all of the guides speak Spanish fluently, which helps them build closer ties to the predominantly Latino families of Fruitvale.

Such close contact means that guides are in a prime position to intuit the social subtleties that can make or break young adolescent life, and meet them head-on. At the school, a group of guides led by Martínez started a secret society called The Brotherhood, which was conceived as a way for bullies and those who were being bullied to change the dynamics of their interactions. The guides approached both groups, told them about The Brotherhood, then swore them to secrecy to boost a sense of intrigue. Afterward, during the school year, guides would take these students from both groups together for walks, lunches, or coffee in order to get them to communicate in a different framework.

“It was amazing to me how this one kid acted a certain way in school, but outside the gates he was the most respectful, super-social kid ever. Once we came back, it’s like he could misbehave again,” Martínez says.

Over time the relationships at school between students of the Brotherhood improved, as well as the particular student Martínez referred to. A similar secret society was started by one of the female guides for female students. But the guides themselves sometimes function as their own safety net, too.

“We call ourselves the suicide squad. Nobody wants to tackle the struggle, nobody wants to tackle the parents, and so we’re kind of doing the dirty work. All of us are super-tight and super-strong,” Martínez says.

“The best advice I can give to new guides is to stick together, and build close relationships,” says Zcoo. “We’re the last line of defense and we don’t let anything get past us.”

The line between guides and teachers can get blurry, however. “We were spending more time with the students than the teachers were, so students were confused, like ‘Are you a guide or are you a teacher?’ But from now on it will be better,” says Naghiyev, who will be transitioning from a guide to a math tutor in the coming year. Now that the school is fully built, guides can work with students in the newly completed sandboxes, rather than sharing classroom space with teachers.

In veritable superhero fashion, all three guides I spoke to see themselves as having different specialties. Zcoo helps students cope with emotional problems, Martínez deals well with tougher students who are in “survival mode,” and Naghiyev does best with students who have academic difficulties. They are also eager to expand the guide system by creating a pipeline to invite additional Fruitvale community members to become guides. They want to create job opportunities for students after high school — or even potentially eighth graders — who could benefit from the responsibilities the position entails.

As the guides give back to their community, they ultimately aim for their students to do the same – to improve their own communities, not abandon them once they finish public education. Getting this message across is no small challenge, and to carry it out would require something subtle, yet powerful, with an impact that will resonate long after it’s over — something, perhaps, like a game.

Epic is a game in two ways. On a day to day basis, the aesthetic of its social structure takes inspiration from role-playing games, but for one week at the end of each trimester, the entire school becomes a full blown role-playing game set in an alternate reality, known as a quest. Quests are devices used in gamified curricula elsewhere, but most of Epic’s quests have themes that intentionally relate to the Bay Area community. This year’s second trimester will repeat the quest Techtopia, due to its huge success last year.

Techtopia is a trans-human society in which students are randomly placed in four different castes: the elite Progenitors, which possess a bionic arm and can download data into their brains; the Chimeras, which are genetically modified humanoid-animals; Bioroids, which are half-human, half-robot; and Clones, which are the lower-class of formerly enslaved organ-donors. The game’s objective is for students to genetically upgrade their personas using bits (Techtopia’s currency) that they are awarded when they complete certain tasks. In math class, for example, students must calculate the cost of a cellular plan that enables telepathic communication from a corporation called Facebot, which controls the economy.

They are given equations, and for every one they solve they are awarded bits. Bits can be spent on upgrades to their stats and attributes or on various forms of entertainment throughout the school specifically designed for Techtopia, including an arcade, a nightclub, and a café where students can buy drinks and snacks.

There is one caveat, however. Progenitors are awarded more bits for the same amount of work, and can skip the disco line and get in for free.

“A lot of kids wasted their money on all of this stuff, and a lot of the kids upgraded. Soon kids started to realize it was unfair, and that they could never beat the progenitors,” said Abbatantuono. A very small number of students did, however, focus solely on getting bits in order to surpass progenitors.

Epic’s staff had hoped that at some point during the quest, students in inferior castes would revolt, but as the days went by without any sign, it seemed unlikely. However, on the last day of Friday during second period, kids suddenly began to gather and hold up papers saying, “Stop everything” and “The club is so classist.” A revolt had begun.

“It was apparent that there were a couple of students who took leadership roles in starting the rebellion,” says Negash, who played the mayor of Techtopia.

The faculty then called for a break to debrief and plan their next moves. Students said that it was unfair that they were randomly assigned roles, and that some were given more privileges than others. Epic’s faculty then decided to switch the unequal dynamic, where Progenitors had to pay three times the amount for everything in the game while the lower classes got things for free. Then, the game resumed. The students still weren’t happy.

“This is not what we want, we wanted it to be fair, equal — everyone should have the same rights,” says Abbatantuono, paraphrasing what a student said at the time. Teachers and guides were ecstatic.

“The unstated learning outcome of what we wanted students to understand was that class exists. So what do you do when you’re in that kind of society?” he adds.

Epic’s next new quest will be “Oakland in the ‘60s,” in which students learn about their own community’s history. On Wednesdays during the trimester, students will prepare for the culminating week-long event with “journeys” that allow them to take on roles such as community member, city manager, and civil engineer— all of whom will have their own agendas regarding public planning, rezoning, and the Bay Area’s history of “white flight.” Using their own knowledge and information, students will engage in debates, vote on decisions, and respond to new conflicts that the teachers will design for the game. The quest will then officially begin with the death of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and continue through the rise of the Black Panther Movement. With this quest, the staff hopes that students will look beyond their present and into the past, and appreciate how Oakland played a major role in the nation’s history.

While many education researchers are skeptical about gamification in schools, others are enthusiastic. “Frankly, if [gamification] helps students and teachers to be more engaged, that’s super. But it’s not really that transformative,” says David Williamson Shaffer, Professor of Educational Psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Game Scientist at the Wisconsin Center for Education Research. “[But] approaching subject matter through role-play, like taking on the roles of urban planners — that’s really transformative. What Epic is doing sounds promising.”

By having students engage in these weeklong quests, Epic wants its students to take on different perspectives and to learn by seeing through a lens that is radically different from their own — and not a moment too soon. Other academics, such as Brad Hokanson, Director of Educational Futures at the College of Design at the University of Minnesota, have found that role playing and “having a narrative framework [is extremely important], especially for this age group,” as it can can help middle school students handle information and imagine outcomes and scenarios that might otherwise seem impossible to achieve.

“Some of our kids in particular have this street narrative that they have to deal with, as in, ‘This is who you are, your life has already been predestined for you,’” says Abbatantuono.

Quests, then, help promote students’ development. “It’s easier to engage in harder conversations when you’re not you than when you are you, because by the end it still hits home,” Hatcher says.

A gamified curriculum may sound like fun in theory, but in practice, the transition from a traditional school can still be tricky. According to a seventh grade Epic student named Melany, “It was a bit weird at first. But I like how the school is based off of how each person does, and how it focuses on your own individual level.”

Melany finds the point system was more engaging than the traditional grades used in public schools. Although the previous year’s badges were confusing to keep track of, they did motivate her and her fellow students to earn more points and be competitive in their assignments. As for the quests, Melany says, “I liked them a lot because they had a lot of emotional teamwork, and that’s what a lot of us need to work on.”

Epic is still a school in its infancy, and a lot of work and time is required to improve its gamification, quests, and meeting the sheer variety of students’ learning needs. Synthesizing all of these disparate threads into a heroic narrative for every student is no small task. At the end of the day however, Epic must still measure its success like any other school.

“We use benchmarks and benchmark data, as well as teacher data,” Hatcher says. “We’re aligned with the Common Core Standards of California, and last year most of our students showed growth but we weren’t at proficiency. This year will be better — more data-driven. Last year was less data-driven to get the model locked in. The model comes first.”

Hatcher continues, “As a school, we have to figure out what it takes to make our neighborhood better. It shouldn’t be about how many kids get to leave, go to college and never come back, it’s about making these children see themselves as resources to improve their community.”

From the guides’ perspective, Epic is a phenomenal success. “At the end of last year, students were crying. They didn’t want to leave the campus,” says Martínez. “In the beginning parents weren’t really sure, like, ‘Is this really going to work?’ but this year they were excited to come back and see us again.”

Right now, parents wonder what will happen when their children leave Epic and end up at a standard high school. Plans to open a high school in Fruitvale with the same model as Epic — depending on its continued success — are under discussion.

After one year, Epic has crossed the first threshold in its own Hero’s Journey in having a successful year, and must still go through many trials to establish itself as a force to be reckoned with. It’s easy to be idealistic in education, and in many ways Epic could be perceived in that way. But whatever happens, it will be worth watching Epic closely to see whether the success its role-playing and community-based model could be applied to broader public education reform in America.

•

Stefan Kielbasiewicz is an editorial assistant for The Brooklyn Quarterly. He is a journalist and poet, as well as the co-president of the Student PEN at the University of York in the UK, where he is sitting his final undergraduate year in English Literature. He resides there as a Polish/American citizen.

Stefan Kielbasiewicz is an editorial assistant for The Brooklyn Quarterly. He is a journalist and poet, as well as the co-president of the Student PEN at the University of York in the UK, where he is sitting his final undergraduate year in English Literature. He resides there as a Polish/American citizen.