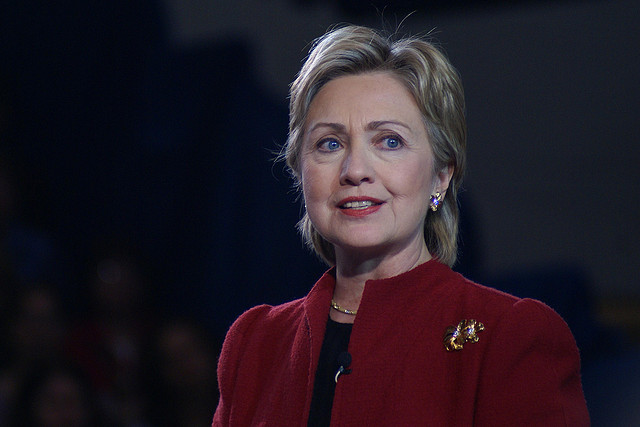

Image: Marc Nozell (Flickr)

Several months ago, word leaked out that President Obama, in a spirited off-the-record exchange with reporters aboard Air Force One, had distilled his foreign policy doctrine into one four-word slogan: “Don’t do stupid shit.”

The remark was an irreverent riposte to the growing clamor for an assertive foreign policy doctrine and, more importantly, was borne of frustration with the increasingly critical tone of his skeptics.

On August 10th, a new figure joined their ranks. In an interview with Atlantic columnist Jeffrey Goldberg, Hillary Clinton declared: “Great nations need organizing principles, and ‘Don’t do stupid stuff’ is not an organizing principle.”

Clinton’s words echoed those of many others who have criticized Obama for “leading from behind” and pursuing a cautious path in foreign affairs. Obama, his detractors allege, is alternatively reckless, feckless, naive, or timid. Recent events, such as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria’s (ISIS) beheading of American journalist James Foley and Egypt’s joint military operation with the United Arab Emirates in Libya without American knowledge, have left pundits grasping for Obama’s organizing principles.

In general, there is nothing wrong with organizing principles. Hillary Clinton’s, however, are particularly problematic. Her Pavlovian instinct for military intervention in response to perceived threats has facilitated catastrophe when enacted and courted danger even when not. And for a Democratic base that has long decried the continuities between the foreign policies of George W. Bush and his successor, Clinton’s approach feels stunningly anachronistic.

Not only did Clinton fail a fundamental progressive litmus test when she voted in 2002 to authorize military operations in Iraq, but more than a full year after the invasion, as evidence of absence supplanted absence of evidence concerning weapons of mass destruction, she continued to miss the writing on the wall. “No, I don’t regret giving the president authority because at the time it was in the context of weapons of mass destruction [and] grave threats to the United States,” Clinton said. “… Clearly, Saddam Hussein had been a real problem for the international community for more than a decade.” (In 2007, long after Iraq had descended into chaos, Clinton again refused to apologize for her vote during her first presidential run.)

In 2008, she flaunted her hawkish credentials on Iran in multiple debates and interviews. Pondering a hypothetical use of Iranian nuclear weapons against Israel, Clinton promised that this “would provoke a nuclear response from the United States.” In a later interview, she added, “Well, the question was: if Iran were to launch a nuclear attack on Israel, what would our response be? And I want the Iranians to know that, if I’m the president, we will attack Iran…We would be able to totally obliterate them.”

While Clinton may have exaggerated her views to make headlines in a bitterly contested presidential race, her underlying policy objectives have been remarkably consistent over the years. In 2007, shortly after Clinton expressed rare reluctance to intervene in Darfur, Chicago Tribune journalist Steve Chapman reminded readers: “[D]on’t bet that she’ll stick to that position if she’s elected. It goes against type. Clinton favored intervention in Haiti in 1994. She favored intervention in Bosnia in 1995. She favored intervention in Kosovo in 1999… Before the Kosovo war, she phoned Bill from Africa and, she recalled later, ‘I urged him to bomb.'”

It would not be the last time Clinton encouraged a president to drop bombs. As Secretary of State, Clinton became a firm advocate for the 2011 American intervention in Libya, an operation whose early success long ago gave way to widespread mayhem.

Now, as she gears up for the rapidly approaching Democratic primaries, Hillary Clinton is doubling down on her muscular foreign policy. In the Atlantic interview, she voiced support for arming the Syrian rebels: “I know that the failure to help build up a credible fighting force of the people who were the originators of the protests against Assad… left a big vacuum, which the jihadists have now filled.”

This is a dubious claim, made all the more so by its timing. Clinton’s conversation with Goldberg coincided almost simultaneously with the launch of American airborne attacks in Iraq against ISIS, the brutal al-Qaeda offshoot whose terrifying string of military successes is due in large part to its stash of American weaponry that it confiscated from the Iraqi military. Clinton’s implication that arming the Syrian rebels would have yielded a substantially different outcome in Syria is implausible at best, foolhardy at worst.

For their part, Clinton’s backers point to her broad support within Democratic circles and publicly express little concern about her views on foreign affairs. Following her Goldberg interview, Brian Katulis of the Center for American Progress openly disparaged Clinton’s dovish critics: “I don’t think they’re as organized on foreign policy as they used to be. … They kind of went home, went to Wall Street and ‘Occupied’ that or something. I don’t know where they are.” But as the nation collectively recoils from the prospect of further military misadventure, Clinton increasingly stands out among likely presidential contenders in advocating an aggressive foreign policy posture.

Back in October 2000, late in her first Senate run, Clinton delivered a speech at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. There, she expounded on her foreign policy convictions, or — to use the more germane term — her organizing principles: “There is a refrain… that we should intervene with force only when we face splendid little wars that we surely can win, preferably by overwhelming force in a relatively short period of time. To those who believe we should become involved only if it is easy to do, I think we have to say, ‘America has never and should not ever shy away from the hard task if it is the right one.'”

Clinton won the Senate seat that November and, in 2002, happened upon the golden opportunity to demonstrate her fidelity to those organizing principles by voting to authorize the use of force in Iraq. That she followed them to a T is proof of her consistency, but everything that came after leaves one longing for “Don’t do stupid shit.”

Jay Pinho is a freelance writer based in Brooklyn, New York.

Jay Pinho is a freelance writer based in Brooklyn, New York.