Lauren Elkin

image: Penguin UK

Editor’s note: The Oxford English Dictionary defines “psychogeography” as “that branch of psychological speculation or investigation which is concerned with the effects on the psyche of the geographical environment.” Coined in 1955 by the Marxist theorist Guy Debord, the term was inspired by the concept of the flaneur, an urban wanderer and connotes playful or inventive ways of navigating urban space. Psychogeographers walk city streets as an act of creativity; they re-imagine the city and its re-imagines them. In her new book, essayist Lauren Elkin challenges psychogeography as the exclusive purview of men. Through her own experiences and the characters of historical women from journalist Martha Gellhorn to novelists Jean Rhys and Virginia Woolf, Elkin talks back to those such as art historian Griselda Pollock who believe, “There is not and could not be a female flâneuse.” This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

•••

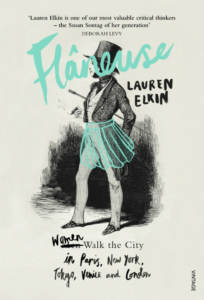

“I walk because, somehow, it’s like reading,” Lauren Elkin writes in her new book, Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice and London. “You’re privy to these lives and conversations that have nothing to do with yours, but you can eavesdrop on them. Sometimes it’s overcrowded; sometimes the voices are too loud. But there is always companionship. You are not alone. You walk in the city side by side with the living and the dead.”

It’s an appropriate quote to introduce Lauren’s book, an insightful examination of the “determined resourceful woman keenly attuned to the creative potential of the city, and the liberating possibilities of a good walk.” I recently interviewed her via email. As she told me, “The flâneuse is a woman who goes where she’s maybe not supposed to go, who defies boundaries.” — Michele Filgate

•••

MF: In the chapter on Venice, you write, “The labyrinth of the city is built to foster desire. Everything we want, disappearing around the next corner, always a few steps ahead.” Did you become more attentive and attuned to your own desires once you moved out of the suburbs and started walking everywhere?

LE: When I left the suburbs I became autonomous, because no longer reliant on anything but my own energy. If I had a desire I could chase it. It’s the nature of desire that it will always elude satisfaction; the moment we have one thing we want another. The city makes this enjoyable, it turns our desires into a state of movement, a game, a play.

MF: There’s a certain privilege that comes with even being able to walk along city streets. How can the idea of the flâneuse expand to include all women?

LE: I’m not sure it’s really up to me to answer that; I certainly wasn’t trying to speak for “all women.” I make certain generalizations based on my reading and walking but I was hoping more to contribute to a conversation about women’s engagement with the city, whatever shape that might take, whatever terms they might choose to put to it.

I write in the introduction about the way that psychogeography and urban walking is a big phenomenon in the UK, you regularly see articles about walking in the mainstream press there, but they’re always by and about men. And once I started researching the book — and since it’s come out as well — I found just endless numbers of women who love to walk, who walk and make work from it, or just walk for its own sake. We need to hear much more from different intersections of gender, race, class, and all manner of physicalities.

MF: How are flâneuses different from flaneurs? What particular challenges do they face as opposed to their male counterparts?

LE: It’s important to distinguish between flâneuserie and flânerie because the way we experience the city is so different depending on our gender, among other factors like race, class, physical ability, and so forth. In nineteenth century Paris, when the figure of the flâneur really gained popularity, womenk — really no matter what their class – were not supposed to be out on the street alone. Or if they were, they were subject to a whole host of codes and restrictions. So the flâneuse, by daring to walk, is immediately violating those codes.

MF: In your chapter on Bloomsbury, you mention that Virginia Woolf used to walk around London looking for inspiration for her books. “The streets gave her everything she needed. As she walked through the city, she would rewrite scenes in her mind; the life she saw around her seemed ‘an immense opaque block of material to be conveyed by me into its equivalent of language.’” By engaging with the city she saw around her on the page, she was able to capture a certain moment in time. Does the flâneuse need to be emotionally distant from what she observes?

LE: This a key place where the flâneuse is distinct from the way we usually think of the flâneur. He’s generally thought of as being this emotionally detached figure, taking in the urban spectacle, watching the crowd but not part of it. I don’t think women can afford to be emotionally distant from the city — and why would you want to be anyway?

It is not a neutral act to walk in the city, as a woman, and I’m not sure it ever was for a man, flâneur or otherwise. But in any case this is the basis of my claim to define a flâneuse as a figure unto herself, rather than a female version of a male figure. The flâneuse is a woman who goes where she’s maybe not supposed to go, who defies boundaries. There’s nothing detached about that.

I don’t think Woolf is emotionally distant from the city. As she writes in a 1930 letter to Ethel Smyth: “I cannot get my sense of unity and coherency and all that makes me wish to write the Lighthouse etc. unless I am perpetually stimulated.” Such stimulation, she explains to Ethel, comes from engaging with the world – from “plung[ing] into London, between tea and dinner, and walk[ing] and walk[ing], reviving my fires, in the city, in some wretched slum, where I peep in at the doors of public houses.” For Woolf the relationship between the city and creativity is a very physical one.

MF: You grew up on Long Island, but have lived in Paris for over a decade. You’ve also lived in Tokyo, London, Venice, and Hong Kong. Does your fascination with the flâneuse come from an innate sense of wanderlust?

LE: It’s more innate even than wanderlust — it’s driven by a basic curiosity about the world and about the experiences that are available not only by changing geographic location but by venturing out into new emotional territory.

I write a bit in my chapter on Jean Rhys about this charming habit I notice in my students, that I remember from when I was their age: they’re willing to throw themselves into emotional situations that someone older and more protective might steer clear of. It takes such bravery to chase down the unknown — I think we lose that as we get older.

So maybe that’s part of what the wandering is about — a willingness to be open to being in different physical or affective spaces that might not be comfortable but which are challenging and rewarding in different ways. There’s a lot to be said for staying in one place — I’m so much on the move at the moment that I’m longing to resettle in my flat in Paris — but there’s so much to be gained from venturing out, with all the encounters that can generate..

MF: Have smartphones helped or hurt the modern day flâneuse? On one hand, it’s easier to find your way around a city. On the other hand, that makes it seem less adventurous. And the biggest worry, of course, is how distracted everyone is. In NYC most people walk around with their eyes glued to their phones. (I’m guilty of doing that.)

LE: The smartphone can’t hurt you if you don’t let it! It can keep you from engaging with your surroundings, but just as we make a conscious choice to use the engage with the city in a different way by flâne-ing around, we can also make the decision to leave the phone in our pockets or handbags or wherever. I guess it’s helpful if you’ve got yourself so lost that you need Google Maps to find your way home. But there are more creative uses being made of smartphones and the city; I think of this great group called the Loiterers Resistance Movement out of Manchester, founded by this amazing woman Morag Rose.

There is a joy to digital flânerie but surely that’s best practiced at home on your computer on a rainy day…

MF: In your chapter on protests, you talk about the day that you went from not feeling connected to protestors to becoming one of them. One often thinks of the flâneuse as a solitary person, but when it comes to marching, you say “It makes us feel stronger to be part of a group.” Is a flâneuse inherently political, alone or in a crowd?

LE: I suppose she is in the sense that everything is political. But it took me awhile to understand where I personally could fit into some kind of activism. I didn’t feel connected to protest movements at first — I’m thinking in particular of the marches against the Iraq War in 2003 — because I knew enough conservative people to know that they didn’t take things like that seriously. As if a bunch of people in Manhattan chanting “No blood for oil!” were going to make Bush and Cheney go — you know what, they’re right, it doesn’t make sense, let’s let it go. But I ended up in a police kettle one day while walking home from the library and that’s when I realized that people get dragged into history whether they want to be or not, and so I might as well stand up for people who don’t have a choice.

I do write that it makes us feel stronger to be part of a group but I also write at great length about the skepticism of group-think that George Sand and Mavis Gallant write about — the two flâneuses in that chapter. When I started going to marches in Paris I did feel the power of protesting all together, but I also experienced the feeling of joining with a group and being literally led astray by it, carried on a wave of excitement and subversion, when these hooligans took control of the group and marched us directly into traffic.

It’s great to march but you have to have a good sense of who you’re marching behind. I think particularly in the last year in the UK and the US we’ve seen a lot of people get caught up in a populist movement that’s founded on hatred and intolerance. How many people got on that bandwagon thoughtlessly? And what I’d like to know is do they regret it, seeing the chaos it’s caused.

MF: Speaking of protests, we’ve just seen a worldwide effort on every continent to protest President Trump, and a TIME cover story about the movement. How is the Women’s March related to some of the historical protests you wrote about in your book?

LE: Wasn’t that incredibly moving? It really was every continent, even twenty scientists on a boat in Antarctica “marched!”

I wrote about women’s marches in history in a piece for the British website The Pool, specifically the women’s march on Versailles in 1789. I had two main points I wanted to make. One was very basically that women are enormously powerful when we come together. As a result of the march on Versailles the king and his family were made to come live in the center of Paris instead of off in their suburban palace; the king was also made to sign the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen. So much for the idea that protests don’t achieve anything.

The other point I wanted to make has to do with a flippant remark I made in Flâneuse – that the French Revolution really kicked off not with the storming of the Bastille in July 1789 but with the women’s march, which took place on the 5th of October that year. I wrote that kind of glibly but in the days preceding our own Women’s March I came back to it. Only seven prisoners were freed when the crowds stormed the Bastille that July 14th – it doesn’t sound like it actually achieved very much. But it was incredibly symbolic that this fortified castle was stormed at all.

We remember the Storming of the Bastille not because it in itself achieved anything but because it was stormed. It felt good to storm it, for the people who took part in it, and it was very inspiring to hear that it had been stormed, for people who weren’t there. Just as I felt incredibly proud of all the New Yorkers who stormed Terminal 4 in response to the Muslim Ban.

Women around the world stood together and it renewed my faith in humanity, and my will to resist. “Ten thousand citizenesses, armed with good muskets, could make the Hôtel de Ville tremble,” Flaubert’s radical feminist boasts in Sentimental Education. The White House fucking trembled on the 21st of January.

MF: In your chapter on Agnès Varda, you say: “Looking, not simply appearing, signals the beginning of women’s freedom in the city.” But how can we observe what’s around us and be completely free of the male gaze?

LE: I was writing about Varda’s 1961 film Cléo de 5 à 7 which is about a pop star whose entire sense of self is built around her beauty. On the day when the film takes place (a nice nod at modernist city novels like Ulysses or Mrs Dalloway) Cléo walks around Paris awaiting the results of a biopsy which will tell her if she has stomach cancer. She has to become aware of her insides in a way she never had to before (it’s true for so many of us, in the kingdom of the well, as Sontag puts it; we only notice the inside of our bodies when we’re ill).

As she walks, as she encounters the weird vicissitudes of Paris, she’s rethinking her relationship to herself, to the people around her, to the city itself. And Varda’s camera gradually moves from showing us Cléo from the outside to allowing us to see the city from her perspective. It’s through the act of observing, and through the encounters she has in the city which help her to live her life from the inside, instead of constantly regarding herself from the outside.

Image: Flickr/Tom Babich

But learning to observe is definitely not something that is restricted to women in the city! “I’m learning to see,” Rilke writes in the Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge. And learning to see, for me, was also about not having the right to look away; it comes with responsibility towards the other people out there on the pavement.

To cast that responsibility in gendered terms: for some men (hashtag not all men) that interpersonal responsibility means allowing women autonomy on the streets, and not seeking to assert their power over them by harassment, or worse. I think the true definition of freedom for anyone in the city is being able to move through it neutrally, if they so desire.

MF: Do you think the flâneuse can ever really know the city she spends time in? I know you say in the book that “…even the places I once knew intimately, I’ll walk over them again and know them in a different way.” Is part of the appeal of being a flâneuse that no walk is ever exactly the same?

LE: Never the same river twice, isn’t that what they say? No two walks are ever the same, no. We’re slightly different and the world is slightly different. But I don’t feel this way in any city I walk in; in Paris I want desperately all the time to know it, to walk more of it, to draw more of it into me. In other cities I can get terribly bored repeating the same walks all the time.

Being a flâneuse isn’t static, it isn’t because I love to walk in Paris that I’m a great flâneuse in any urban setting; you have to fight for it. That’s why living in Tokyo was so hard for me at first: I was expecting the city to be laid out for me, like New York or Paris; but I had to engage with it in a different way to enjoy it. No matter how good a walker you may be there will always be places that could defeat you if you let them.

•••

Michele Filgate is VP/Awards for the National Book Critics Circle and a contributing editor at Literary Hub. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, The LA Times, Tin House, Slice, Gulf Coast, O, The Oprah Magazine and many other publications.

Michele Filgate is VP/Awards for the National Book Critics Circle and a contributing editor at Literary Hub. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, The LA Times, Tin House, Slice, Gulf Coast, O, The Oprah Magazine and many other publications.