Joseph Grazi’s Happy Place is probably a lot weirder than yours. Instead of palm trees on the beach or croissants at Sunday brunch, Grazi’s Happy Place (which happens to be the name of his show) features cat skeletons and monkey skulls, reclaimed newspapers and over 100 bats. In Grazi’s Happy Place, at ArtNow NY in Chelsea until November 30th, death is everywhere. And that’s exactly the point. The show meditates on dualities: life and death, beautiful and ugly, rational and irrational. TBQ sat down with him to discuss the pieces in the show, art as philosophy, and why ladybugs aren’t that much cuter than moths.

TBQ: Can you tell me a bit about the show in general?

JG: So this show, one would look at it and think the show is about death, and death is definitely the aesthetic, but to me it’s more about the sacrifice, really the sacrifice that’s involved with death.

TBQ: You say sacrifice in death. Whose sacrifice? Is it the dying person’s sacrifice?

JG: I call these pieces “altars” because they’re really shrines to an animal that was. The rose is inside of the piece kind of dying, too. And as this thing is dying it’s kind of on this slab, following this ancient tradition, and if you think thousands of years ago we would sacrifice the beautiful women because we had this homicidal rage towards beauty in some way. Now we’ve kind of just diverted that or at least in the modern world, but we have this homicidal rage still towards flowers.

TBQ: I feel like the piece would have a really different feeling if I saw it when you had just put the flower in there, and then I saw it at the end of the week when you are about to replace the flower.

JG: It’s organic art to some degree. So there’s nothing you can do about that. Since to me, when it comes to a rose or life in general, every phase of decay. Obviously from an aesthetic point, people want the beautiful alive flower, but the joke is that the second you snip it, whether you put it in water or not, it’s dead. You’ve killed it. You’ve decapitated it. You might be letting the blood flow inside of it for a little bit longer, but you’ve just killed this beautiful thing, really for no reason to some extent.

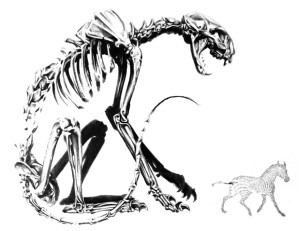

So the bones from the show represent something that is intrinsically scary or inherently scary, something that you fear for no logical reason. All of us have skeletons inside of us. If we had x-ray vision no one would talk to each other. We would all be afraid to see each other. It’s following this — to me — ancient tradition of giving a luxurious and expensive feel to death. These are a little bit like modern mummies.

TBQ: Would you say that you’re finding the beauty in death or finding death in everything that’s beautiful?

JG: A lot of the things that excite me as an artist are the inconsistencies in the way that we do view each: the way a cockroach is gross and you have to kill it, but the ladybug is beautiful, and it’s lucky. Or a moth is ugly, kill it, but the butterfly is beautiful. All of those are very inconsistent in the way that we see life and the way we view life aesthetically in general. So to me, death is just as beautiful, but I find it the most interesting that some parts of death are beautiful to a person and some parts are not.

TBQ: It’s interesting that you talk so much about aesthetics and colors. You were talking about the zebra, the ladybug, the butterfly. For mammals at least, a lot of them, when it’s just the skeleton they look the same, give or take.

JG: And it’s what’s inside of them. Their skeleton looks exactly like that while they’re alive and it doesn’t freak people out, but the second you can see the skeleton you’re all of a sudden freaked out by that, and it’s for many different reasons. It reminds us of our own mortality, and it reminds us that we are in fact animals. Another overall point of this show is that we fear what lurks beneath us.

TBQ: So was the purpose of these pieces to make people confront what irrationally freaks them out?

JG: It’s to take the things that they normally fear and, without changing the subject matter, try and change the lens through which they see them.

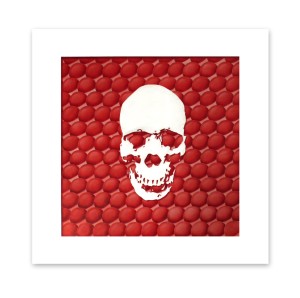

TBQ: Why the newspaper clippings on that piece?

JG: The newspaper clippings are a very human thing representing just mass information. Also, it’s kind of garbage. It’s something that we throw out. It’s something that we don’t care about on an aesthetic level. So I’m trying to use that as something visual, as something that I personally find beautiful.

TBQ: There’s natural history in the skull, and the history that we create and record and shape in the newspaper.

JG: Right. And re-appropriation in taking different mediums that one person has thrown out. In death and garbage, both of them are kind of thrown out and buried to some degree.

TBQ: The heart with the bats has to be one of the most striking pieces. How did that come to be?

JG: I haven’t killed them myself. They’re collected from enthusiasts and hobbyists from all over the world. These ones, to some degree, are kind of smuggled from Indonesia via Quebec. So it’s this whole operation ring that I’ve had.

TBQ: Do you find that a lot of your art is philosophically-oriented?

JG: It’s certainly philosophically-oriented, but it’s very philosophical science-oriented, social science, things like that. Man as the animal is something that I’ve been interested in forever.

TBQ: Would you say that visual art is a good way to enter into these deeper conversations? I think that there’s something about reacting viscerally that gives philosophical debates more immediacy.

JG: We’re very visual people. Obviously our sight is the craziest sense we have. It’s the one sense that we would be the most lost if we didn’t have. I also think that for this specific conversation it’s the conversation about aesthetics. So to be an environment that is aesthetic, you’re going to have an easier time coming to conclusions and coming up with questions, because this is not a show that is trying to answer a question and come up with answers. I don’t have the answers.

TBQ: But you do seem to have if not answers, a strong point of view. It’s not that open-ended in terms of what people should take away.

JG: Right, absolutely. But definitely this work is a way for me also to flesh out my own ideas.

TBQ: If everyone were to come into your show completely misunderstanding it, except they can take one thing away, what would you want that to be?

JG: It’s that life should not be worth living based on what it looks like. You shouldn’t judge life aesthetically, to think about why you find that spider disgusting but that ladybug cute and that praying mantis interesting, why a puppy is so adorable, but a rat is so ugly.