‘The camera cannot lie; but it can be an accessory to untruth,” wrote Sir Harold Evans in the introduction to his 1978 book, Pictures on the Page. As the photo editor of The Sunday Times for 14 years, Evans framed his book with a warning that “thanks to photographic montage or editing, we can ponder events, irrefutably down in black and white, that never happened.”

While we live in an age of Photoshop and stock photography, an artificial version of the world reflected on billboards, in magazines, and mocked with tumblr, the veracity of images used by news outlets is often taken for granted. Recent gaffes—such as when the BBC used a decade-old photo from Iraq to illustrate the massacre in Syria, a viral picture claiming to show a Syrian child sleeping on the grave of his parents (that was actually part of a Saudi Arabian art project), and Fox News’ use of footage of “random sad Asians” in their South Korea ferry disaster coverage—are labeled “innocent” and quickly forgotten.

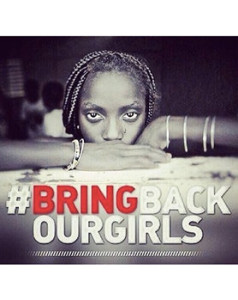

The misuse of photography becomes even more problematic when amplified by the whirlwind of social media. Unverified images are misused and then magnified, retweeted and reposted into crowd-determined truth. While part of a larger trend of unreliable photographs, the pictures used in the viral #BringBackOurGirls campaign highlight a larger crisis in photojournalism: We want to be entertained, even if that means lying to ourselves.

The Twitter campaign #BringBackOurGirls helped galvanize a response to the kidnapping of 276 Nigerian girls by the Islamic militant group Boko Haram in early May. Accompanying the hashtag are images that have been reposted thousands of times—by everyone from Chris Brown to the BBC. The most retweeted photo is powerful and direct, a woman staring at the camera with an unflinching gaze. Another popular image accompanying the hashtag is a close up of a crying face, tears darkening each cheek like an oil slick. Putting a face to the crime is an undeniably powerful tool: these are girls that could be our daughter or sister, our friend or self. The only problem? These are pictures from Guinea-Bissau, three years ago, of girls that have never been kidnapped.

The Twitter campaign #BringBackOurGirls helped galvanize a response to the kidnapping of 276 Nigerian girls by the Islamic militant group Boko Haram in early May. Accompanying the hashtag are images that have been reposted thousands of times—by everyone from Chris Brown to the BBC. The most retweeted photo is powerful and direct, a woman staring at the camera with an unflinching gaze. Another popular image accompanying the hashtag is a close up of a crying face, tears darkening each cheek like an oil slick. Putting a face to the crime is an undeniably powerful tool: these are girls that could be our daughter or sister, our friend or self. The only problem? These are pictures from Guinea-Bissau, three years ago, of girls that have never been kidnapped.

They are the work of photographer Ami Vitale, an award-winning photojournalist, who teamed up with the Alexia Foundation for a project called “Tradition, Women’s Rights and Circumcision in Guinea Bissau, Africa.” The focus was on the Fulani, a Muslim ethnic tribe, and how larger changes like globalization had affected women and their access to education. The larger intent of the project was to highlight the dignity and resilience of the Fulani. When interviewed by the New York Times about the misappropriation of her images as part of the #BringBackOurGirlsCampaign, Vitale responded:

This is why I feel so enraged, because I was trying to not show them as victims. They are not victims. Using these images and portraying them as victims is not truthful. The story I did was a hopeful story.

The girls in the images are Jenabu Balde and Umou Balde and were highlighted by Vitale to show how girls were able to get an education and tribal life was improving. Vitale didn’t know the photos had been misused until someone from the Alexia Foundation spotted the image. She was furious:

This is personal, Even if they weren’t dear friends, it’s the principle, we can’t pick up any photo and use it out of context. I can’t help but wonder that they thought this was O.K. just because my friends are from Africa. If it were white people from another country in the photos, this wouldn’t be considered acceptable.

Reflecting on the nature of her project and the duty between a photographer and their subject— the contract to represent truthfully and respectfully — she continues:

I feel a sense of responsibility to the people I photograph. I go into communities and I make a promise that I will be responsible with their images and that I will deliver the message that they articulate to me. We are responsible as photographers and journalists when we make promises to do justice to their stories and honor them in the way that they have honored us by sharing their stories.

She raises an important point: If someone uses them for their own story, how will their voices ever be heard?

It is not just the media’s confusion of Guinea Bissau with Nigeria or the conflation of a child crying after circumcision with a terrified abductee, the misuse of these images transforms symbols of female power and independence into icons of weakness and subjugation. We need to #BringBackOurGirls—as the people they are, not caricatures that live halfway around the world. If we use pictures without understanding where they come from and what they represent, we will only end up in a house of mirrors of our own prejudice. A camera cannot lie, but an image can.

·

Genevieve Bentz is an editorial assistant for The Brooklyn Quarterly. A freelance writer and photographer, she graduated from Princeton in 2012 with a degree in English and Creative Writing.

Genevieve Bentz is an editorial assistant for The Brooklyn Quarterly. A freelance writer and photographer, she graduated from Princeton in 2012 with a degree in English and Creative Writing.