It seems fitting that TBQ’s founding editors Tristan Snell and Jane Carr interviewed Jonathan Butler and Eric Demby, the entrepreneurial pair behind the Brooklyn Flea, during TBQ’s first week in the Made in NY Media Center. Having just joined the neighborhood, we walked over to a nearby building overlooking much of DUMBO, where the Flea shares office space with an architecture and design firm. Large and bright, the offices proceed under the watchful eyes of a sleepy but friendly dog. We might have been reading too much into his expression, but we like to think we met with canine approval.

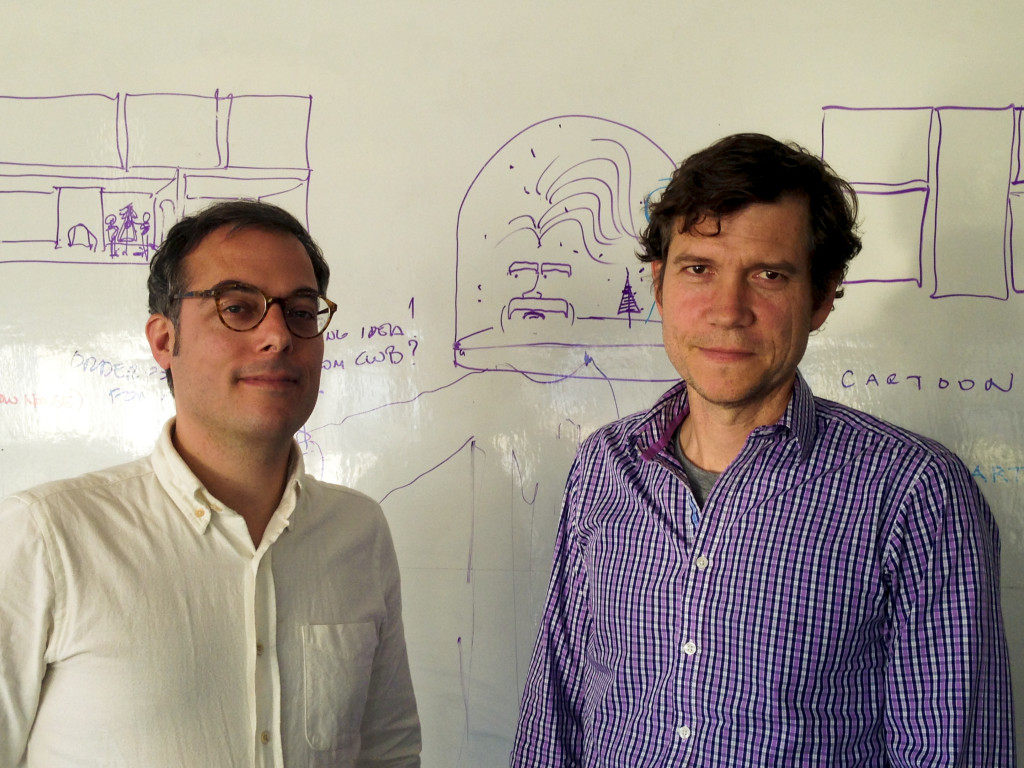

Since Jonathan and Eric founded it in April 2008, the Flea (along with Smorgasburg) has become a cultural force in Brooklyn and well beyond. Late on an early fall afternoon, beneath an antler chandelier and surrounded by color-coded and neatly labeled bins of fabric swatches, Jonathan and Eric answered questions about partnering up to make and grow the Flea. As the conversation progressed, we moved into a nearby meeting room with photo collages of the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges and a giant well-used whiteboard. Surrounded by such images of Brooklyn’s history and the dry-erase scribblings of its future, Jonathan and Eric described their partnership and gave us a preview of their next venture, a beer hall in Crown Heights with a food court where up-and-coming vendors can make a name for themselves. Look out for it in 2014.

This conversation has been edited for succinctness and clarity.

CONCEPTUALIZING, STARTING UP AND BRINGING IN THE SWEDES

TRISTAN SNELL: Our first issue is called Garages and Grassroots, and it’s all about entrepreneurship across a range of different areas from tech to culture to politics to the arts. We wanted to talk to you guys about your own entrepreneurial experience and your role and observations about the broader ecosystem for startups and entrepreneurs in Brooklyn, in New York City, etc.

JANE CARR: To start things off, we are particularly excited to be talking to you two since we also are co-founders. Could you start off by saying a bit about how you came together?

JONATHAN BUTLER: Sure. Well, we knew each other back from around 2006. Eric was the Director of Communications for Brooklyn Borough President. I’d already started Brownstoner [a Brooklyn real estate news website]. So we met in that capacity…

ERIC DEMBY: Adversaries, really.

JB: …Press relations. We’d actually had one discussion about Eric running an editorial thing that I was working on at the time, but that didn’t pan out. Then, when I initially posted about the idea of the flea market, he emailed me saying he’d been having similar thoughts. We had a meeting of the minds in October or November of 2007 and were off to the races from there — market launch in April 2008.

TS: And did you guys have any support from the Borough President’s office? Or, what were the initial support elements?

JB: Well, really, the initial support was that we had this media platform that was the biggest blog in Brooklyn, which was really all we needed. I mean, it was a leg up from having to put up posters on telephone poles and hope people would show up, right? We knew within 48 hours of first announcing on Brownstoner that we were on to something — around 80 to 90 vendors responded. And then it got picked up a lot by the blogs and newspapers, so the wind was at our back with the media aspect of it.

ED: Those things are definitely true, and I think that the thing we also had was the support from each other. There’s this meshing of our backgrounds, our connections and our personalities that still happens today… It’s like a 1 plus 1 equals 3 sort of thing. Jonathan was born and raised in the city, uptown. My family’s mostly from Brooklyn. My mom grew up on President Street, in Crown Heights. And my grandfather grew up in Williamsburg. And then working in the Borough President’s office, I got deep down into the whole borough of Brooklyn, seeing [borough president] Marty [Markowitz]’s perspective.

JB: And knowing how to do some of the grassroots stuff.

ED: Right, right. The real behind-the-scenes stuff. How do community boards work? What’s happening with the Department of Health? Even knowing how to handle the regulation of food at the market turned out to be this key to the success. Many markets get shut down because they don’t know what they’re doing.

JB: We’re both kind of anal. And even early on, we were pretty sure we were going to be big and under a microscope of sorts, so we were very careful to do everything properly. You know, I would be surprised if there’d ever been a flea market before that had actually filed with the Department of Buildings.

TS: So you had an institutional knowledge of exactly how to navigate?

JB: Well, no, but there was a whole political process. I’d gone early on to Fort Greene’s [New York City] Council Member, Tish James, and said, “Hey, there’s this block at Catholic High School we think would be great.” So she made the initial connection with the school. We were sitting in her office, and she just picked up the phone and called the liaison at [the NYC Department of Buildings] and asked what we had to do.

TS: A lot easier than calling 311.

JB: Yes, exactly. But you know, part of that is she already knew. Because she knew me for three years from Brownstoner, and she obviously knew who Eric was from Marty, so there was a level of trust there. And I think that was another distinguishing thing. You’re never going to do everything perfectly, but whenever there have been any problems, we’ve tried to address them really quickly and present ourselves as safe and trustworthy. If you’re a politician, a developer, or whoever, we want you to know that you’re not going to end up looking bad if you take a chance on a project [of ours]. On the flipside, we’re probably going to end up doing something that enhances and helps invigorate the neighborhood, stimulate the economy, whatever. We’re going to do our darnedest to make sure there’s not something stupid that blows up in your face and makes you look bad. So I think as time has gone on, that level of trustworthiness and reputation has helped a lot.

ED: Today, everybody and their brother thinks it’s cool to be a Brooklyn start-up business, especially in the food and creative arena. And I think that six years ago we were trying to start something that was big and that was, I think, fairly ambitious in terms of where Brooklyn was at that moment.

JB: And even in terms where the market was, because, you know, it wasn’t in Brooklyn Heights. Fort Greene was still… there were a lot of people coming out there for the first time, coming out of the C train and looking around and being like, “Wow this is beautiful. I didn’t know this existed.”

ED: And also people from Fort Greene being like, “What is going on? There are so many people around here I can’t believe it.” Now, the biggest real estate developers in the world are in Brooklyn. But at that point that was definitely not the case. Our big challenge back then, which lasted for several years, was how to get people from outside the neighborhood to come to this market. Those are six short years where that evolution happened. At that time, we could go to city government or some other institution for help, and they were like, “Wow, that’s amazing, that’s so cool,” and now it’s like…

TS: “Tell me something I haven’t heard before.”

ED: “Figure it out [yourselves].”

TS: Did you start off having this broader vision that’s come to be?

ED: Well, we knew that the only way to sustain a market of this size — the only way to create a business that would be profitable — was to bring people and make it more than just a neighborhood or local attraction. So we knew that meant [attracting people from] Manhattan and regionally. I don’t think that we were ever thinking that people from Sweden would have this at the top of their list the way they seem to now.

SMORGASBURG, PROMOTION, AND RAMEN BURGERS

ED: You know, the Red Hook food vendors were like the seeds of the Smorgasburg foodie “fetish-ization” of Brooklyn. A cool thing to do was to venture out to the Red Hook Ball Fields and eat from the food vendors who set up on the weekends. People would play soccer there, representing their country of origin, and then there would be a food stand representing that country. But those guys did not have permits. [U.S.] Senator [Chuck] Schumer and all these people were trying to save them, but they’re hard to save because they have some challenges with language and that kind of thing. So I was aware of all that, and we kind of saved them by giving them this satellite location [at Smorgasburg]. So when you went to the Flea at the beginning, there would be these gigantic lines for the pupusas… And then there were some other more cool, new-school places, like Salvatore Brooklyn Ricotta, mini cupcakes from the Kumquat Bakery, and McClure’s Pickles — all these brands that are now part of the imagination.

TS: What role do you think the blogs played in all of this taking off? And the emergence of Twitter right around the same time?

ED: Twitter came a little later; at that point it was still early Facebook. But we had our own blog and email newsletter. It was a slightly different level of echo chamber than it is now, but they were there. It was really the New York Times that got the Flea going.

JB: There was a fashion spread.

ED: Yep. The first day at the Flea, they came and did a photo shoot, and that was on the cover of the Style section the following Sunday, which helped a lot. There was a three-page preview in New York magazine with a map of where all the markets and vendors were going to be, so as it got closer, it started to really ramp up. So yeah, blogs definitely played a role. I think Brownstoner helped a lot. One person would tell another person and another person and that was really a support network for us. It wasn’t just a home run. It was a home run on the first day, and the second day was really good, too, but then it was rocky for a year or two. It was like good, bad, good, bad — so we were just always pushing, pushing, pushing.

JC: You mentioned Kumquat, and we’re really interested in how, over the course of the last six years, you’ve observed changes that you were instrumental in making. One way that I would be really interested to see that playing out is if there are other vendor relationships that you’ve seen overlap and blossom in a similar type of way.

ED: There’s so many. There is that spirit of collaboration and friendly competition because everybody knows where their turf ends and begins. Like with the Ramen Burger thing, instead of being envious of the Ramen Burger line, just be like, that guy’s bringing in like a thousand people a week.

TS: Be near the Ramen Burger guy.

ED: Probably Keavy [Landreth] and her cupcakes are one of the best examples, and her sister is now the nanny of my kids… Like Asia Dog: they started out selling at a bar, a trophy bar in Williamsburg, and then they got a spot at the Flea in 2009, and now they have their own, they have a small restaurant on Kenmare Street in the city. They’ve become sort of media darlings of their own. And Mighty Quinn’s of course. That guy was always telling us how we saved his life. He was playing in some touring band that opened for the Wallflowers, after having been a long suffering chef… He was living in New Jersey with three sons and kind of losing his mind, and he came in and barbecued five kinds of meat for us and we loved it. And he brought his giant smoker to one of the first Smorgasburgs in 2011 with this huge line right out of the gate, and now he has a restaurant in the East Village that got two stars in the Times, and that’s hard to do in New York… so those are probably the best ones… And there’s also our own beer hall that we’re opening in February or March that will have four permanent food kiosks, like a Flea Court.

JB: When you think about it, our internal mission is to keep giving vendors places to grow… We did a similar thing at South Street Seaport. We called it Smorgasbar. It was summer, we had a shipping container, and it was a bar with eight food vendors set up around it. The more we can do, the more opportunities we can give them to grow, the more tight-knit and closer we all can stay, because then they don’t need to go off and do other things if we can keep providing opportunities. That keeps everything stronger, I think.

TS: So kind of along those same lines, you talked a little bit about the evolution and boom in all things Brooklyn — food cultures and all that. From the role you guys have played and with what you’re describing about giving vendors space to grow, what have you guys seen in that evolution of the ecosystem itself over the past five years? Have you seen any changes in how the new folks approach starting up compared to how they did back in ’07, ’08, ‘09? What are the differences that you guys have seen from how new people come in and start up and expand now, as opposed to five years ago?

ED: That’s a good question. Well, we get more applications for food, because people see it as like, “I’m just gonna quit my job and I’m gonna be a food vendor at the Flea.” I don’t know what they see — stars and dollar signs.

JB: Liberation and self-actualization.

ED: Right, that too.

JB: More than big money.

ED: Jonathan and I are those people now — something that people aspire to now — which is crazy and weird. So I think a lot of the applications are more highly evolved. They know how competitive it is to get in. Some of them are more sophisticated, like, “I’ve been a chef at blah blah blah, and I have this concept I want to do…”

JB: And some come in with sample menus and little designs for how they would set up their booth, and what their sign’s going to look like, and stuff like that.

ED: Because they really, really want to get in, and they’re now acutely aware. There have been stories about how it’s harder to get into the Flea than Brown.

JB: Not Princeton, though.

ED: That meme’s gotten out there somehow, so they know how hard it is, and we can see them shaking, and it’s really funny. We try to calm them down. As the market gets bigger, and there are more and more different kinds of food, in a way, the people that apply get quirkier. The smart ones are like, “I’m not going to sell barbecue, because there’s the most famous barbecue guys already there.”

TS: So, they are trying to find micro-niche spots.

ED: Which is smart. They didn’t just come in being like, “Mac and cheese!”

ED: This woman today has all these different kinds of mini whoopee pies or whatever, and that’s smart, because we don’t have a whoopee pie person. So it all ends up being like a punchline in a sitcom about Brooklyn. But I would definitely say that people have evolved. And as we’ve opened markets in other cities, it’s helped us not to take that for granted. Because other cities do not have anywhere near as highly evolved of a culture of this kind of thing. New York is different than other cities in so many ways, but I think the idea of going all in with a booth at our markets has caught on, and it’s infectious. It’s inspired all kinds of creative ideas, whereas in other cities, the applications for food vendors are more straight-ahead.

JB: But to be fair it’s like, when Smorgasburg started, we had three years of food at the Flea Market to just organically grow without any pressure. So we had a pretty good base when we started. Eric’s right. In these other cities, it’s a lot harder to find.

EXPANDING, REPRESENTING AND OPENING A BEER HALL

JC: You’ve expanded to other cities in a very practical, but also in a more representational way by thinking about how or what Brooklyn represents culturally. How would you connect your expansion — and what you’ve seen it bring to other cities — with what you think Brooklyn represents?

JB: It’s hard to say since we have just this week decided to close Philly down. We opened Philly in June, and D.C. in September. D.C. is thriving, and Philly had a huge opening day but has been gradually trailing off since then. It’s hard to know what to make of the difference. One of the big differences — as we talked about earlier — was either the presence or absence of media, and Philly is a bit of a wasteland when it comes to media. The launch was fantastic. We left that opening day being like, we’ve got another Brooklyn on our hands here, this is fantastic. And the quality of the vendors was great, probably better on opening day there than it was in opening day here in 2008. But without a reason it just sort of gradually lost steam. For us to stay engaged there, we needed to get it to some scale, and it was shrinking.

TS: In terms of the media what do you think was missing?

JB: Well, they had one dysfunctional newspaper, and, like, a couple blogs.

TS: And that’s it?

JB: And I feel like there’s a certain demographic of New York who is sitting there and just devouring all this stuff all day long. I just didn’t get the sense that there was that saturation.

ED: Yeah. People would show up at the market, and somebody may have told them about it. But when you walk around the Flea and Smorgasburg and you listen, which is basically what Jonathan and I do now because there’s not much for us to do there besides that, somebody will be like, “Oh yeah, Ramen Burger,” and someone else will be like, “Oh I heard that the Ramen Burger guy blah blah blah, I heard he went to Taiwan last week,” and like, “Oh no, he didn’t go to Taiwan, he went to Hong Kong…”

JB: People are actually giving history lessons to their parents about this vendor. People are just so into it. They actually know more about this than I do.

TS: Has that happened in D.C. yet?

ED: It’s starting to.

JB: Yeah, whatever it is, it’s growing. A lot of people go every week. Part of it could be economic, too. D.C. is definitely much more thriving economically right now than Philly. And the Philly location was also a bit off the beaten track. It was in a neighborhood that we thought felt kind of Brooklyn-y, but there was not a lot of built-in foot traffic. But by the same token, in 2008 in Fort Greene, there was not a lot of foot traffic going past. You know, the nice thing about our business model is that we can go and try, and if we have to shut it down, we won’t have lost a dollar. It’s very inexpensive for us to try things. And if it works, great. If it doesn’t… Now we’re kind of one-for-two, I think. It’s hard to know, but it’s a thing we think about all the time. Honestly, I think the geographic growth will continually be largely driven by the right opportunity falling in our lap more than by us being like, “We need to be in Portland. Let’s go.” Because from our experience, it’s very hard to go convince someone who doesn’t know who you are that you’re so great and they should roll out the red carpet for you. Whereas if there’s a landlord or a city that wants you there to start with, the whole thing is much, much easier. But if someone called us with this amazing location in L.A. and were like, “Why don’t you start doing a market next year?” we’d probably think pretty seriously about it. But we’re not going to go spend two weeks in L.A. driving around looking for the perfect schoolyard or whatever.

TS: But in terms of, say, launching in D.C., what do you think Brooklyn means there?

JB: So in Philly we called it Brooklyn Flea Philly. And we felt mid-stream that that may have been a mistake. And in D.C., we called it District Flea. I forget exactly how we branded it, but it’s clear that it’s a market we’re doing, that it’s a Brooklyn Flea production. But Philly is known for its local pride.

TS: And their not-liking-New-York-ness?

JB: Yeah. We heard there were people who were literally saying, “Well I’m not going to go to that thing.” You know, like we were arrogant Brooklyn guys or something ridiculous like that, which never occurred to me. I always thought that it doesn’t matter what we call it, and that if it’s a good market, people will go to it. But it’s a disadvantage to not being on the ground there yourself.

ED: I think it’s funny to go to D.C. and talk to folks there. Jonathan and I exist in this Brooklyn bubble where there’s some tangential connection to us, so we’re aware of things — we read, we hear about it when we go out at night, friends will tell us stuff, we’ll overhear something. We’re immersed in it. When we’re inside the snow globe, it’s a bit hard for me to talk about what it’s all about. But I think that increasingly there’s this mentality that Brooklyn is for hipsters. But then, also, what is a hipster? To me, it’s kind of a meaningless word. So I dismiss that stuff. But then I try to think about what that means to other people, and I think it kind of means young people. So in D.C., the market has a similar sort of age group. It’s actually a bit more mixed ethnically, but it’s the same kind of mix of people in their 20s and 30s with their parents and other people their parents’ age. So I don’t really know what that is, but it seems to be like a gravitation of families back to cities, with a lot of people starting young families. And then, also, instead of in New York where you have a lot of young creative people, in D.C., you have more of this lobbyist, lawyer, government kind of thing going on. The people are a little bit less cool-looking, but they have a similar mentality.

JB: I would say actually they were a little cooler-looking than I expected.

ED: Right, D.C. continues to surprise us with how much cooler it is than I think it used to be. Apparently, according to everyone that lives there. I think they’re all really proud of how cool they’re becoming? [laughs] You know, it is what it is.

JC: I agree.

ED: But I think it’s a trap to start talking about what Brooklyn represents.

JB: Early on, we got asked a lot about what attracted people to the Flea. The word we kept coming back to was “authenticity” — a reaction against mass-produced stuff and big box stores. And the nice thing is that it’s not just shopping. It’s an experience. You can go there, and even if you don’t buy much, you had this cool experience, and you interacted with interesting people, and there’s something satisfying about that. I think, to the extent we’re able to recreate that experience in other places, I don’t think it requires, you know, a spectacular artisanal food level.

TS: Is it about the smallness of the vendors and the directness of the transactions, or…

JB: No, it’s less specific. It’s just a vibe.

ED: I think some of this comes from the base of how we curate the market. Having antiques and vintage things brings people back in time or something like that. I don’t know what that means, but it does something to people. There’s a pride that develops. I think it’s the same feeling in D.C. right now as there was in the beginning of the Flea: maybe I know some of the people that are selling, and I connected with some other people on social media about it or whatever, but it’s really more that you go there, you see people you know, and people are psyched. It’s constantly reinforcing itself. I went there, my friends were there, and that means it’s a good place to go. But it’s not a store, and it’s not a park — it’s created for them but not some prefabricated experience. It’s participatory. It relies on them to be there, and so there is a bit of ownership to it. And then on top of that, it actually is a convenient thing to do. It’s the ultimate noncommittal weekend day: I don’t want to do anything today, but I don’t want to sit at home. It fits, especially when you have kids: I don’t really want to go to a museum because my kids will touch the art, and I don’t just want to go to the playground because that’s what I do every weekend. So I’ll go there because I kind of don’t know what’s going to happen. It’s not like you’re going to have some gigantic insane experience, but you can go there and just hang out, and something fun will happen. I’ll be able to eat there, and no one’s going to kick me out, and also I’ll get to be outside. Brooklyn, D.C. — that works everywhere. It’s really just this question of, how, in a city, should that happen, and then whether there are enough people to sustain the business.

JC: That’s great. You touched on this a little bit, but what is on your horizon? What’s next?

ED: (laughs) We can’t even say.

JB: Well, we’re moving to a new winter location, so we’re not going be in the old Williamsburg Savings Bank. We’re going to be in a new location in Williamsburg, in a much bigger indoor location at 185 Wythe Avenue. Around Thanksgiving is when we’re moving there. New locations always bring new challenges and some extra work.

ED: It’s 47,000 square feet and going to have 175 vendors: food, Flea, and Smorgasburg in the winter, which we’ve never had before.

JB: And then, the really big thing is the Beer Hall opening in February or March, which is 9,000 square feet, and neither of us has even waited tables before in our lives, so…

ED: I’ve waited tables once.

JB: Oh, you did? Okay. So we’ve got service. We’ve got to learn the restaurant business really quickly.

JC: Where is the beer hall, again?

JB: It’s in Crown Heights, on Bergen Street, between Classon and Franklin avenues.

ED: We took over the Park Slope P.S. 321 Flea Market a couple weeks ago. So that happens every weekend now and is around 30 or 40 vendors. It has more of a focus on antiques, though at some point it’ll probably have food, too. I mean, all kinds of stuff is going on. Alice Waters is coming next month to do a book signing and just be there, and this other guy, John Besh, a New Orleans celebrity chef guy, is coming to make gumbo.

JC: Always a good time. I grew up eating duck gumbo, so anytime anybody says gumbo…

ED: Apparently he’s famous, I’d never heard of him.

JC: Everybody likes gumbo.