Who is a map for, locals or foreigners? What should it depict, regional beliefs or internationally agreed upon borders? How can it accurately reflect the world? Recent outcry over an atlas of the Middle East that didn’t include Israel highlights the inherently political nature of cartography. Like anything that purports to illustrate reality, a map is both an educational tool and an ideological weapon: a piece of paper that controls our perspective by representing and legitimizing our own bias.

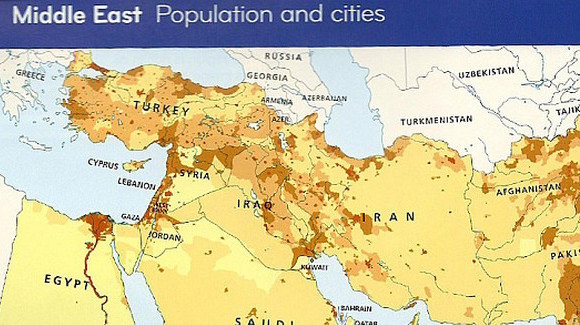

Since the end of May, HarperCollins has been selling a specially developed atlas “for schools in the Middle East.” [Note: The page has since been taken down.] The publisher says the “maps give in-depth coverage of the region and its issues” and the “mapping is accompanied by facts, diagrams, graphs, cross sections, and statistics at country, regional, continental and global level”—all detailed and researched, but lacking the entire country of Israel.

Gaza? Yes.

Israel? Vanished.

The erasure was first covered by Tablet magazine, talking directly to a HarperCollins representative who said Israel’s presence would have been “unacceptable” to their Gulf customers and that the publisher was working according to “local preferences.”

The Global Jewish Advocacy group has since issued a statement saying that the exclusion of Israel is “inexcusable,” and that “erroneous, politically motivated maps only serve the interests of those who continue to reject the existence of Israel and seek its eradication.”

HarperCollins author, journalist, and vice president of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, Alex Brummer called the map “outrageous,” saying, “In effect, HarperCollins achieved what the former Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad threatened at the stroke of a pen: it wiped Israel off the map.” Brummer hopes that the foreign policy and diplomatic community will be “fully engaged in combating anti-Semitic tropes . . . that still form part of the curriculum and textbooks in many parts of the Arab world.”

HarperCollins has since apologized on their Facebook page and promised the remaining stock will be pulped, but reviews for the book on Amazon show the PR firestorm is far from over.

“A lot of Middle Eastern countries do not like USA, why not leave it out of the map?” wrote one highly ranked comment. “An infantile wish cannot erase the reality of the existence of the State of Israel. Is this delusional map offered along with a book on Holocaust denial?” asked another. The online debate quickly turned to the nature of cartography itself: “When maps are drawn up to satisfy political demand how can they be called maps, they are just works of art . . .” It’s a good question.

In the political landscape no less than the visual one, recognition is key. 160 of 192 United Nations member states recognize Israel— including all of North and South America (except Cuba), Europe, and Asia (except North Korea, Malaysia, Bhutan, and Indonesia). Whether Israel should exist is a question that will not likely soon be resolved; whether it does has been a moot point for over half a century. Removing it from a map is cowardly and juvenile, the equivalent of sticking your fingers in your ears and shouting in order to avoid hearing something unpleasant.

But should we rest comfortably on the premise that majority rules? Where does that leave the likes of South Ossetia, South Sudan, or Crimea, to say nothing of Palestine itself?

Perhaps these aren’t questions HarperCollins can be fairly charged with answering. But that doesn’t make it any less wrong for a publisher to accede to the local political ideas of the audiences for whom its products are intended. Just because people want to believe the world looks a certain way does not alter its physical composition. The exigencies of global capitalism, in other words, should not control how we perceive, learn about, and approach the world. This is an example of the perils of educational publishing: HarperCollins providing delusion its customers will pay for.

While the tumult over the atlas is a byproduct of the clash between politics and the free market, the problems raised by its distortion speak to the larger perils of power and prejudice, especially when shaping children’s perception of the world. Mapmakers are ostensibly peddling a reflection of a real-world geography in addition to the political paradigm playing out on its surface. But to what end? Do we use maps to learn about we don’t know or to obscure complicated landscapes in order to make them more pleasant to digest?

Needless to say, no map can be completely accurate. Transferring the round world onto a flat plane means unavoidable distortion. Geometry always wins. Beyond the act of representing three dimensions in two, the subject matter itself is not static: cities and bodies of water are in constant flux. Like a butterfly in a collector’s frame, maps offer only a shadow of the mobility, volatility, and fragility that exist in an area before it is pinned down. Skewed representation of the world is an inherent part of map-making. Recent debate has centered on these flaws —why is Europe at the center? Why do we still use the 1569 Mercator map projection, which distorts the size of continents like Africa? These issues of bias are compounded when, like the HarperCollins atlas, maps are used as teaching aids.

That’s all before regional power dynamics come into play: even if we could transfer a carbon copy representation of the physical world onto a piece of paper, there remains the inherently biased task of the publisher determining who should be on the map, and where. This is where HarperCollins has given in to local pressure and produced an ideological map rather than a geographic one. The danger lies in their equivalency: Gulf state students don’t realize that the map they are looking at is nothing more than propaganda.

This is an atlas that goes against what an atlas claims to do, and in the process reveals how artificial our perception is. For all the customers of the book, an Israel-less world is real: an illusion that is in direct denial of the physical, tangible world. It is not just that an Israel-less maps exist, it is also that a generation of students are being raised with that world-view. The problem is not that there are regional resentments, the problem is that something like the HarperCollins atlas panders to these tensions and perpetuates the delegitimization of an entire culture, race, and nation in order to make money. It is capitalist anti-semitism: removing all trace of Jews in the Middle East in order to sell books. The free market has morally failed.

Despite how flawed maps are, they still matter. We need them to navigate geographical, political, and social landscapes. We need a world with borders in order to know how to cross them. Realistic maps, in so much as they are, help us deal with the uncomfortable, the unknown, the foreign and strange—the world beyond ourselves. As soon as we can dictate what we want to see, they lose all meaning, power, and use. An atlas of the Middle East without Israel is not a map, it is the vanity illustration of a region living in a fantasy—and ultimately self-destructive—world.

·

Genevieve Bentz is an editorial assistant for The Brooklyn Quarterly. A freelance writer and photographer, she graduated from Princeton in 2012 with a degree in English and Creative Writing.

Genevieve Bentz is an editorial assistant for The Brooklyn Quarterly. A freelance writer and photographer, she graduated from Princeton in 2012 with a degree in English and Creative Writing.