Romeo and Juliet

They never felt this way I bet

So don’t underestimate

My point of view…

—Madonna, “Cherish”

An early scene in Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho (1991) opens with an extreme close up of River Phoenix shuddering, eyes rolled back in his head. We know from an earlier scene that his character, Mike, has narcolepsy, and is prone to sudden bouts of sleep. Still, it’s not clear what’s happening on screen.

The film alternates between close-up shots of Phoenix’s face—we can see every pore of his young skin—and iconic images of life in the Pacific Northwest: salmon jumping up river to spawn and water lapping on the shore of a mountain lake. Then the camera slowly pans out to reveal Mike seated in a chair in a hotel room on the brink of climax with a body hovering over him. As he recovers from the orgasm, the shot pans, exposing the person pleasuring Mike as a tired old man who pushing cash into Mike’s jeans. Later we learn that Mike is part of a group of male hustlers who exchange sex, mostly with older men, for money, food and drugs. This opening scene is emblematic of much of the film, which follows Mike on his meanderings through the Northwest while using visual motifs and heightened sound to depict his point of view or consciousness.

Later in the film, an abrupt shift in perspective occurs as Van Sant toys with the line between film and documentary. Two young men, looking slightly off camera, describe their experiences selling sex. While we don’t hear the questions they’re asked, or see whom they are addressing, it seems they have been prompted to tell stories about their lives as hustlers. Their responses emphasize the casual brutality of sexual exchange. These moments, which feel like candid interviews with real people, stand in stark contrast to the dreamy visual symbolism—if not the actual narrative content—of the rest of the film (which also concerns itself with Portland subculture and its marketplace for the sex trade).

My Own Private Idaho was Van Sant’s third feature film and the last in what is often referred to as his “Portland trilogy.” As a film, it raises ethical questions about documenting countercultures, which are by definition insular social groups that derive meaning from resistance to prevailing norms. In film studies, considerations of the ethics of documenting such situations, where the documenter is “outside” the culture are commonplace.

Documentary theory pioneer Bill Nichols argues in his essay “Why Are Ethical Issues Central to Documentary Film Making” that “ethical issues are central to documentary film-making,” which always carries an inherent tension between the one holding the power of representation and the person or culture being represented. What has been less considered by theorists of documentary film are examples of drama or fiction that integrate elements of that genre to create an artistic vision with a distinctive purpose. While biopics and docudrama dramatize real events, My Own Private Idaho is unique in its weaving of real people and their stories into a fictional world. Perhaps this particular strategy—the integration of the real into the fictional—is a response to the ethical tangles at play in documenting cultures that one sits outside of.

Upon its release in 1991, the film helped to establish Van Sant as one of America’s most innovative independent filmmakers. Reviewers praised its “enormous insight” and “shaggy grace.” Critics reserved the most resounding praise for the film’s two leads: River Phoenix, who portrays street hustler Mike Parker, and Keanu Reeves, who plays Scott Favor, the mayor’s son who has fallen deliberately from his father’s grace. The story follows their close friendship and experiments with life on the street until he turns twenty-one and inherits his family fortune.

Both Reeves and Phoenix were established stars when Van Sant made this film. Their foray into the world of hustlers, and play with homoeroticism and gay sex, was bold. Phoenix’s performance, in particular, received high praise for its raw and emotional honesty. Today, many fans view the film as a kind of memorial—both for Phoenix who died three years after its release from a drug overdose, and for Portland, now “a vanished bohemian city.”

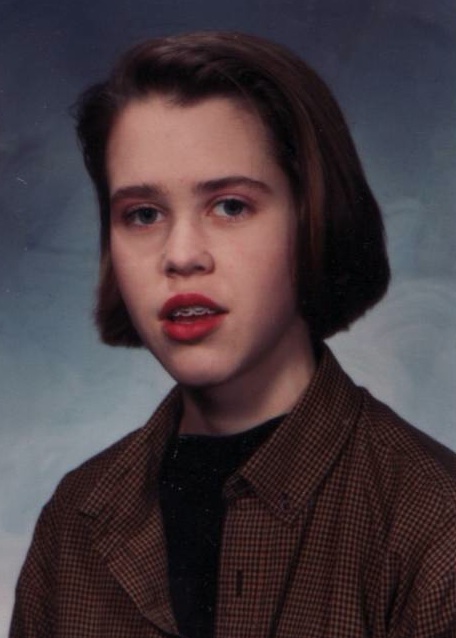

When I saw the film in 1991, I spent most of it enthralled by the recognition of familiar friends and places. I watched it as a portrait of a city that I had just left, and a counterculture that I had been a part of: a group of kids who hung out downtown in Portland, which was then a small, economically depressed city with a vital all-ages music and club scene.

Van Sant shot My Own Private Idaho on location in Portland with non-actors in many of the roles. Many of the extras were cast from street kids and the school kids (like me) who hung out with them. Some of us were still in high school at the time and living at home. Others were dropouts and runaways who were hustling, panhandling, and/or tapped into the emerging network of services for young homeless people. We hung out on the street and in coffee shops, smoking and exploiting the promise of bottomless coffee.

We—boys and girls alike—wore eye makeup, thrift-store blacks, and danced at clubs called The City, Confetti, The Escape. We hugged every time we met and every time we said goodbye. Some of us returned home at the end of the night. Others went to squats – abandoned warehouses near the train tracks. Many of us had been abused, kicked out for coming out, or otherwise mistreated by parents or authority figures. (I was one of the privileged ones who desperately wanted the freedom to do and be what I wanted separate from my loving, if disgruntled, parents). What joined us together across different kinds of privilege – the homeless and the domiciled—was a desire to create a world that was truly ours, where we could be safe from the power and pressures of a world run by adults.

Flash forward to 2015. I am middle-aged and producing theatre for a Portland-based company called Hand2Mouth. For the past year Hand2Mouth has been working on a project called Time, A Fair Hustler, which revisits My Own Private Idaho to look back at “old Portland”—the generally-accepted term for both the city in the early 1990s, as well as the particular countercultures during that era—and to explore the tremendous changes the city has undergone.

The ethical terrain and problem of representing youth cultures has shifted since Van Sant did research for My Own Private Idaho, as has Portland’s identity as a city. At the forefront of a national trend towards urban development, Portland has become the most gentrified city in America.

Time, A Fair Hustler, in part because it is a response to My Own Private Idaho, emphasizes those changes and mirrors some of Van Sant’s reliance on documentary and interview.

The performance of Time, A Fair Hustler, picks up the lives of the characters where the film left off—re-imagining them nearly twenty-five years later. It asks where they are and what they have become—and ultimately invites audiences to reflect on the Portland of then and now. The script operates around character’s memories, which start out as spoken recollections that slowly gather into dramatizations. The one person who does not exist in the present day is Mike (Phoenix’s character). The others are in constant pursuit of him. In some ways he is the phantom, the one who may only ever be a memory, and have disappeared from the present.

The play’s characters also reminisce about the Portland that was once a gritty city of abandoned buildings, diners, and seedy hotels, but was recently named the most “liveable” place in America. Hand2Mouth’s performance, like Van Sant’s original film, uses interviews with a wide range of people involved in the film, including extras, crew, and people who were homeless and living in Portland at the time.

Hand2Mouth’s work has long integrated audience stories into performances. The 15 year-old company is a collective of eight directed by Jonathan Walters, who credits My Own Private Idaho with attracting him to Portland. The company crafts performances over time, through hours of improvisations and exercises in which they create material and eventually develop a script. Over the last seven years, the company’s projects have used methods adapted from social sciences and documentary film, including surveys, questionnaires, and interviews, to collect stories and anecdotes subsequently woven into the performance. The company aims to create a thin and porous line between the autobiographical and the fictional in its theatrical performances.

Hand2Mouth has used this approach for multiple performance-projects. Project X (2008) was an extended time capsule composed of audience memories; Everyone Who Looks Like You (2009) gathered audience and community member testimonies about family secrets; PEP TALK (2014) elicited motivational speeches from audience members, which were spoken in real-time by the performers. Part of the development process of a Hand2Mouth show has entailed exploration of how real stories interact with the playful, fictional space of theatre works. Do participants feel respected? Are their stories treated with dignity and kindness? Ultimately these are also ethical questions about how to treat those whose voices are being represented, and folded, into the spectacle.

Hand2Mouth performances tend to portray highly personal, ‘universal’ themes (memory, family, and motivation). Time, A Fair Hustler is distinct from the company’s other work in that it navigates the politically loaded territory of the loss of “old Portland.” Much of this turmoil stems from anxiety about how the city will absorb continued waves of population growth without any clear development strategy. The play invites the question: how can Portland continue to support creativity in the face of a huge influx of capital and competition for housing and other resources? In such a climate, categories like “old” and “new,” “inside or “native,” grow increasingly fraught. These ideas, though complex to navigate, have shaped Hand2Mouth’s interview process and integration of outside voices into Time, A Fair Hustler.

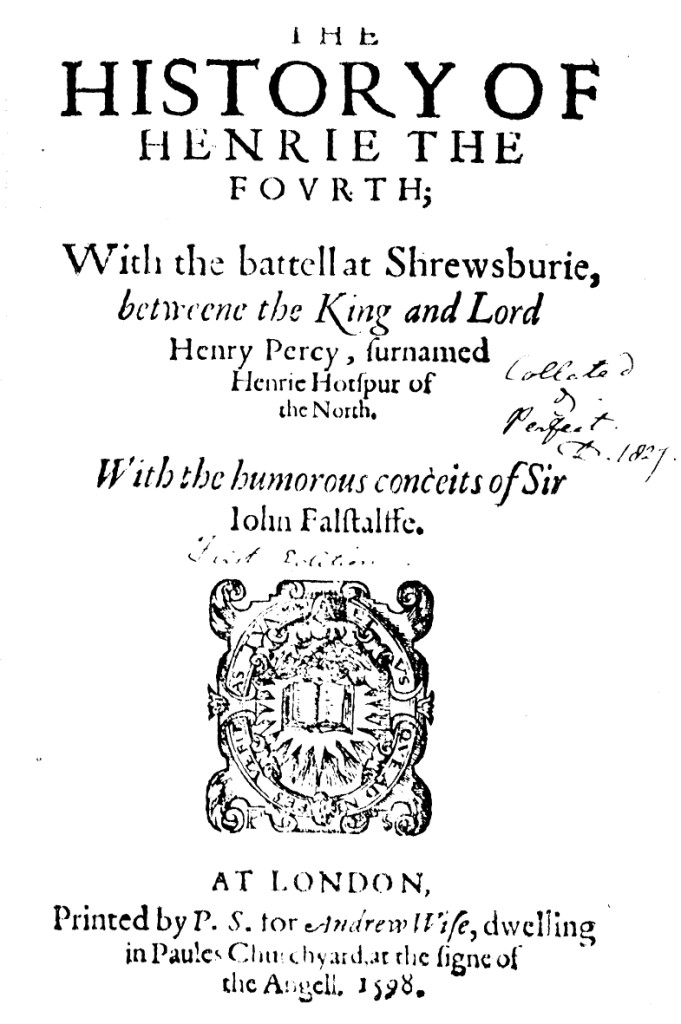

The overall narrative effect of My Own Private Idaho is dizzying. The script is a postmodern blend of three of Van Sant’s previously incomplete screenplays and its language veers back and forth between the formality and jocularity of Shakespearean verse (lifted from Henry IV and Orson Welles’ Chimes At Midnight) and everyday (often mumbled) speech.

Gus Van Sant brought a long fascination with hustler culture to his film-making. The formative years he spent in Portland also appear in his first two films, Mala Noche and Drugstore Cowboy—both of which also featured marginalized groups, namely street kids and drug addicts.

And yet, he was what Portlanders would call more “hills than streets,” a reference to Portland’s Westside “hills” which has traditionally been where wealth has concentrated. (In interviews about Idaho Van Sant describes Scott as “a rich boy… who falls off the hill.”) Van Sant’s father was a fashion executive. The family moved around the country, but ended up in Portland in the 1960s and Van Sant landed at the elite private high school, Catlin Gabel. He left Portland to go to art school East at Rhode Island School of Design, and returned to the West Coast in the 1980s.

According to Mario Falsetto—a film scholar who published a book of interviews with Van Sant recently and is consulting with Hand2Mouth on the development of Time, A Fair Hustler—Van Sant’s interest in young hustlers dates back to his time writing in West Hollywood and watching hustlers and their johns in cafes. My Own Private Idaho pulled material from the world of Portland street kids in the casting, locations, as well as the research that informed Van Sant’s script and the leads’ acting process. The script was inspired by connections Van Sant made with Michael Parker and Scott Green—two men who were interviewed in the final film, and inspired the character of Mike.

In the weeks before filming, Phoenix and Reeves went to Portland to do Method acting style research, where they met with “friends” that Gus had made who were “on the street” and were willing to show them the ropes. Unlike Van Sant’s, their research was done “anonymously” or “guerrilla style.” They went out in character and were “just hangin’”—playing music and carousing, with the extras they met on set, all of whom were involved in Portland street life in some way. When asked by Interview magazine if at any point he felt like “asking street hustlers for information was somehow exploiting them,” Phoenix responded: “I think they were flattered that their story would be told.”

Van Sant’s connections, Parker and Green, weren’t just source material—they appeared on camera. In one scene, Michael Parker talks about his first “date.” He smokes and smiles while describing how he was “this guy… basically raped me… he put a fucking wine bottle up my butt.” This interview is intercut with a second man (Scott) who describes “a really awful experience” with a man who forced him into a date. Despite the raw violence of their stories, Parker and Green convey a sense of pleasure in telling their stories. They smile, smoke, and seem relaxed—even self-assured. One senses that this is not the first time that they’ve told these tales. Their affect works to undermine any notion that they are victims, indelibly marked by trauma. Their stories, while brief, demonstrate Van Sant’s access to the young counterculture the film portrays—and the trust he earned from them.

While many creators of fiction ground their stories in research, what is unusual here is that Van Sant foregrounds this process as creative product. It is not merely research. He (in his mid-to-late-thirties) negotiated with and earned the trust of these young men, and it is this trust that is made evident and visible here.

The documentary sections of My Own Private Idaho highlight ethical questions about representing a youth counterculture that is often exploited by adults. The specificity of the stories also spotlight the brutality of capitalism written on the body, in which a person becomes a commodity in order to acquire money, drugs, and other resources. While Green and Parker—like the fictional Mike and Scott—have found temporary freedom from a world run by adults, they are always forced back into capital exchange with those they seek to escape in order to be free again, if only until the next encounter.

The sadness of hustling is complicated by a later scene in which Reeves and Phoenix are seated in the same diner after being run out of their squat. Their heads slump on the table while Parker – in a what seems to be a coked up monologue – describes his ambitions for the future. He wants to be a famous musician, “with my face on the front of album covers…standing ‘in the back of bigger pictures of myself.” We see Michael in a new light, as both an artist with dreams, and subject to another mode of exploitation in the hustle of commercial music. (This could also be read as a very tongue-in-cheek reference to Reeves’ and Phoenix’s own stardom).

Ultimately, fictions—even disrupted ones like My Own Private Idaho—are great catalysts for taking stock of situations and serve as a measure of the audience’s feelings. Madonna’s “Cherish,” with its call not to “underestimate my point of view,” is the soundtrack to this scene, which introduces documentary-style interviews in a fictional account of life played by fictional characters. Van Sant uses multiplicity of voice invoked through the strategic use of “Cherish” to undercut any singular point of view or experience for the viewer. The song becomes a reminder that every city and every counterculture is made up of multiple points of view, all of which must somehow find a voice and be heard.

To create Time, A Fair Hustler, which premieres this summer at Artists Repertory Theater in Portland, our director Jonathan conducted interviews with a wide range of people involved in My Own Private Idaho, including extras, crew, and others who were part of the subculture of homeless youth in Portland in the late 1980s and 1990—all of which will be woven into the script. The “real” Mike and Scott will also be interviewed. Hand2Mouth’s interviews with long-time residents of Portland speak—as the film does for some—as memorials to a lost city.

When asked to describe how Hand2Mouth will weave the details of fact into the fabric of performance, Jonathan says of the interviews and research: “We will bury [them] into the text of the show as all part of this fictional world.” Despite the strong emphasis on interviews, the show will also embrace theatricality. In part to elude the problem of how to cast the iconic leads without constant comparisons to Reeves and Phoenix, Jonathan has cast them as women. In this revisiting of a beloved film that was inspired by a classic play, Hand2Mouth foregoes the Shakespeare, except for the title, which is drawn both from Henry IV and from Scott’s appropriation of its lines:

What do you care? Why, you wouldn’t even look at a clock, unless hours were like lines of coke, dials looked like the signs of gay bars or time itself was a fair hustler in black leather.?…There’s no reason to know the time. We are timeless.

The integration of interviews into the performance text provides an important level of material detail to our performance. Dramaturg Jessie Drake will mine interview transcripts for interviewee first-witness accounts about life ‘on the street’. She and Playwright Andrea Stolowitz will also draw out patterns that get used when interviewees are deep in recollection: the umms, the ahs, the gaps in speech.

The interviews are also strategic tools intended to work against notions of “new” Portland as the clean utopia, the “liveable” city as which it is so often cast. One interviewee, who was a street kid and “child prostitute” in the late 80s, recalled the details of the sex trade, including “the wall” downtown where she and other underage prostitutes often stood to attract customers. She links her period of homelessness and prostitution to “catastrophic poverty” and parental neglect. Like the interviews in Van Sant’s film, these narrative accounts serve as a reminder of the brutal aspects of being young and marginalized. They also offer an important female perspective absent in Van Sant’s focus on boys and men.

While it’s true that parts of Portland are shiny and new and that one of Van Sant’s ‘own’ hustlers has found success as a photographer for local film and TV, including the television show Grimm, it’s important to note that the same interviewee observed that far from being gone, child prostitution has been pushed East, towards the strip malls of outer Portland. And yet, she noted, the landscape has substantially changed for homeless young people as a result of a growth in social service agencies that provide a range of services including shelter, needle exchange, and professional development to at-risk youth.

In conjunction with the premiere, Hand2Mouth will curate an event series, “Portland: Then and Now,” to generate conversation about Portland and its future. ”Before the Pearl” will be a walking tour of sites from the film (some still there, some lost) that will address the changes since 1990 in NW Portland, where much of Private Idaho was shot. Another event, “Young, Queer, and Homeless,” will invite social service providers and formerly homeless young people to consider how conditions have changed in the last 25 years for marginalized youth. Hand2Mouth is coordinating with local organizations that serve homeless youth to create professional development opportunities in production for the run of the show.

The third and last event in this series will be “A Funeral for Old Portland.” This is especially fitting since one of the final scenes of My Own Private Idaho is a funeral. Scott Favor turns 21, his father, the Mayor of Portland, dies, and he inherits his fortune. Upon this embrace of a heteronormative, affluent life, with prospects for a political career, Scott turns his back on the street and his old friends.

Our funeral will take place in the theatre with eulogies commissioned from interviewees and others who were active in the city in the 1990s. We are hoping that everyone will be there: today’s street kids, yesterday’s street kids; the former mayor and the current mayor; emerging and emerged artists; the moms and dads; young creatives and the old creatives; musicians (who have aspired to their pictures on record covers) and those whose aspirations have only ever been digital. After the eulogies are read we will ask everyone to take a moment to imagine the place they want to live, and to consider: What of “old Portland” do we want to leave behind and what do we want to take with us into the future? Then we will ask people to speak these out loud.

I like imagining this scene, because the story of many 21st century cities is one of transition, and of flux, as new flows of capital come in, many people who are firmly entrenched and have made helped define the city and its institutions, are pushed out to the margins. As we tell these stories of flows of capital and people, it is useful to reflect upon the ways that My Own Private Idaho plays with what Bill Nichols argues in his work: that all fiction can be classified as documentary. Fictions, he writes, are “documentaries of wish-fulfillment…they give a sense of what we wish, or fear, reality itself might be or become.”

Every city had its own subcultures of artists living cheaply in industrial spaces and/or depressed neighborhoods. The story of our generation is the story of gentrification: the story of people choosing urban communities over suburban ones. The question is how we will tell it, and how we act upon it. How do we navigate the paradox of gentrification on which the privileged creative is always on the front line of that change?

In 1990, I left Portland to attend theatre school in Seattle. Later I went to New York for theatre and then London to study performance. As I recall my time in each city the stories are always the same: “In Seattle, London, Queens, Brooklyn, I met artists who were making songs, videos, paintings, poems. We lived cheaply together in shared spaces often zoned for commercial use. We had community gardens. We took public transport, walked, and rode bikes.” Then there was an influx of capital and most of us had to move on, further out, to another borough. The detail that’s missing from this is the part I play in this pattern. As a so-called creative, and one with the economic privilege to keep moving across states and nations, my presence in a neighborhood is always foreboding, a sign of gentrification to come. It is possible that I am both part of the problem and part of its solution.

I moved back to Portland in 2012. I wanted to create a life here for my young daughter, near my parents, the lakes and the salmon. Being here, I am often reminded of my 1990 world and the subculture my friends and I created to try to escape a world run by adults. Twenty-five years later I am the adult. We are the adults and we must seek to find ways to join forces across privilege to create a world – or cities – that belong to us.

•

Jen Mitas is Executive Director of Hand2Mouth, a theatre company based in Portland, Oregon. She has worked in various roles producing and creating theatre over the last twenty years. Prior to moving to Oregon in 2012, she was based in the UK where she researched and taught performance history, devising, and theory at University of London. Her work is informed by a longstanding interest in the ideas and economies that inform the performances we make and the techniques we use to make them.

Jen Mitas is Executive Director of Hand2Mouth, a theatre company based in Portland, Oregon. She has worked in various roles producing and creating theatre over the last twenty years. Prior to moving to Oregon in 2012, she was based in the UK where she researched and taught performance history, devising, and theory at University of London. Her work is informed by a longstanding interest in the ideas and economies that inform the performances we make and the techniques we use to make them.

The author wishes to acknowledge Jane Carr and The Brooklyn Quarterly; all of Hand2Mouth and especially Maesie Speer, Jonathan Walters and Jess Drake; Mario Falsetto for conversations about the film; Carole Zucker for pointing out the significance of the funeral scene; Oregon Humanities and Multnomah County Cultural Council for funding the public discussion components of this project; and JJ for insights along the way.