Picture by Joshua M. Hoover (Flickr)

Judge Richard Posner of the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals is an extraordinarily productive jurist, even by the rigorous standards to which we hold our federal judges. He made headlines last Thursday, however, when he handed down a fiery forty-page opinion that struck down Indiana and Wisconsin’s same-sex marriage bans a mere nine days after he and two colleagues had heard the oral argument.

While the speed of the Seventh Circuit’s turnaround was impressive, perhaps what was even more remarkable about Judge Posner’s opinion was the nuanced grasp of history that it displayed. Again and again, Posner reminded the reader of the shameful tradition of discrimination against homosexuality in our country and globally. He declared on page 10:

“Because homosexuality is not a voluntary condition and homosexuals are among the most stigmatized, misunderstood, and discriminated-against minorities in the history of the world, the disparagement of their sexual orientation, implicit in the denial of marriage rights to same-sex couples, is a source of continuing pain to the homosexual community.”

Fourteen pages later, Judge Posner circled back to history.

“One wouldn’t know, reading Wisconsin’s brief, that there is or ever has been discrimination against homosexuals anywhere in the United States,” he wrote sarcastically. “The state either is oblivious to, or thinks irrelevant, that until quite recently homosexuality was anathematized by the vast majority of heterosexuals … including by most Americans who were otherwise quite liberal. Homosexuals had, as homosexuals, no rights; homosexual sex was criminal (though rarely prosecuted); homosexuals were formally banned from the armed forces and many other types of government work (though again enforcement was sporadic); and there were no laws prohibiting employment discrimination against homosexuals … Although discrimination against homosexuals has diminished greatly, it remains widespread. It persists in statutory form in Indiana and in Wisconsin’s constitution.”

Just two decades ago, it would have been nearly impossible to imagine a federal judge writing those words or the Supreme Court, to whom Indiana and Wisconsin have appealed, entertaining such an argument.

For years, gay rights activists have been making the case that laws discriminating on the basis of sexual orientation—which include same-sex marriage bans as well as legislation that curtails gays and lesbians’ ability to adopt, donate organs, or sit on juries, et cetera—ought to be more harshly scrutinized by the judiciary than they currently are. Their argument goes like this: nearly every law that the government passes will have the effect of disadvantaging certain groups vis-à-vis others, such as limiting the vote to those 18 and over, or limiting certain jobs to those who meet a specific IQ threshold. But gays and lesbians, unlike minors or those who fail to meet an IQ threshold, constitute a uniquely marginalized group that deserves an extra level of protection against discriminatory laws. Much like laws that discriminate on the basis of skin color and gender, legislation that singles out homosexuals for negative treatment needs to be even more carefully examined by the courts for violations of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

Within the Supreme Court’s Equal Protection Clause jurisprudence, there are several factors in deciding whether a group is a “discrete and insular minority” and therefore deserves added constitutional protection, including whether that group is defined by an “immutable” characteristic (meaning that one is born with that trait), whether that trait bears no relation to a member’s ability to contribute to society (a low IQ, for example, is immutable but may affect one’s ability to perform, so the government is justified in using IQ cutoffs for certain jobs), whether the group is politically powerless to change its fortunes at the ballot box, and—notably in this circumstance—whether it has suffered from a history and tradition of discrimination. If the Court finds that the group has satisfied such criteria, then the immutable characteristic is a “suspect” or “quasi-suspect” classification, and “heightened scrutiny” is used to judge any law that the local or federal government passes targeting that group for discriminatory treatment.

In practice, the application of heightened scrutiny almost always makes it harder for the law in question to survive, as it is presumed unconstitutional. On the other hand, a law that affects a group that does not merit heightened scrutiny—like those under 18 years of age—receives what is called rational basis review, the least stringent level of judicial review that presumes the constitutionality of the law. The application of rational basis review almost always results in the challenged legislation being upheld.

Gay rights activists argue that they fulfill all the criteria to be considered a discrete and insular minority. Same-sex attraction is genetic, they say—it cannot be converted into heterosexuality through prayer, psychotherapy, or physical punishment. People who identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual constitute only around 3.5% of the population, and they are often politically powerless to stop majorities from passing anti-gay laws. One’s sexual orientation does not affect one’s ability to contribute meaningfully to society. And even though opponents of equality disagree on all of the above points, it is undeniable that gays and lesbians have been subject to an extensive and terrible history of discrimination.

The activists looked to the Supreme Court’s treatment of racial minorities and women as a template for how things could be. After all, the long history of state-sponsored racism against people of color was a big reason why the Court had decided that race and national origin are suspect classifications, and that laws discriminating on the basis of such deserve strict scrutiny, the most rigorous form of heightened scrutiny. As the Court said in 1964’s McLaughlin v. Florida, striking down a law that banned cohabitation between interracial couples: “We deal here with a classification based upon the race of the participants, which must be viewed in light of the historical fact that the central purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment was to eliminate racial discrimination emanating from official sources in the States.”

The consideration of past, systemic wrongs as a reason for applying heightened scrutiny is articulated even more explicitly in a line of women’s rights cases beginning in the 1970s. In 1973’s Frontiero v. Richardson, Justice William J. Brennan, Jr. invoked the country’s history of sexism as one reason why women needed such protection from laws that discriminate on the basis of gender:

“There can be no doubt that our Nation has had a long and unfortunate history of sex discrimination. Traditionally, such discrimination was rationalized by an attitude of ‘romantic paternalism’ which, in practical effect, put women, not on a pedestal, but in cage … It is true, of course, that the position of women in America has improved markedly in recent decades. Nevertheless, it can hardly be doubted that, in part because of the high visibility of the sex characteristic, women still face pervasive, although at times more subtle, discrimination in our educational institutions, in the job market and, perhaps most conspicuously, in the political arena.”

The part of Justice Brennan’s ruling that advocated heightened scrutiny for women could only garner four votes, making it a plurality opinion that lacked precedential force. But when the Supreme Court revisited the question three years later in Craig v. Boren, it created a form of heightened scrutiny known as intermediate scrutiny for gender discrimination, which subjects laws to a standard of review tougher than rational basis review but not as quite as stringent as strict scrutiny. And in 1996, when the Court further honed its approach to gender discrimination in United States v. Virginia, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, writing for a 6-3 majority, reminded us once again the importance of viewing gender as a quasi-suspect classification:

“Today’s skeptical scrutiny of official action denying rights or opportunities based on sex responds to volumes of history… Through a century plus three decades and more of that history, women did not count among voters composing ‘We the People’; not until 1920 did women gain a constitutional right to the franchise. And for half a century thereafter, it remained the prevailing doctrine that government, both federal and state, could withhold from women opportunities accorded men so long as any ‘basis in reason could be conceived for the discrimination.’”

While the Court has drawn upon lessons of the past to formulate a strategy for combating race and gender discrimination, though, those who hoped for a similarly self-aware approach toward discrimination based on sexual orientation have not been so fortunate. Beginning in the 1980s, in a series of Supreme Court cases that challenged anti-homosexuality laws, gays and lesbians soon discovered that the long history of hatred and discrimination they had been subjected to could in fact be (1) brushed aside, or (2) worse, used as a reason for withholding heightened scrutiny.

In the case of the latter, legal strategy was in part the cause. Rather than using the equal protection clause doctrine, early cases regarding gays and lesbians’ right to live and love freely saw the application of a substantive due process-fundamental rights test instead, which requires a different constitutional analysis. In such cases, the dispositive question is not whether the law uses a suspect or quasi-suspect classification, but whether the law has infringed upon a fundamental constitutional right (such as the right to privacy). If so, the law automatically receives strict scrutiny, while laws affecting a non-fundamental right undergo the more lenient rational basis review. In the seminal 1967 case of Loving v. Virginia, for example, an interracial couple challenged a miscegenation ban on the grounds that the fundamental right to marry included the right to wed a partner of a different race. The couple won in a unanimous Supreme Court ruling, notwithstanding the prevailing attitudes at the time that came down solidly against interracial unions. But when gays and lesbians tried to advocate a similar argument for themselves, the history and tradition of homophobia turned out to work against the targeted group seeking protection.

And so Justice Byron White—author of McLaughlin, member of the plurality in Frontiero and of the majority in Craig v. Boren—found no fundamental right to consensual homosexual activity in 1986’s Bowers v. Hardwick, writing in the majority opinion: “Proscriptions against that conduct have ancient roots. Sodomy was a criminal offense at common law, and was forbidden by the laws of the original 13 States when they ratified the Bill of Rights.” Without a trace of irony, Chief Justice Warren Burger added in a concurrence: “Decisions of individuals relating to homosexual conduct have been subject to state intervention throughout the history of Western civilization. Condemnation of these practices is firmly rooted in Judeo-Christian moral and ethical standards.” Despite the fact that Justice White was part of the unanimous Court in Loving v. Virginia, there was no mention of that case or the parallels to interracial marriage, itself a long-proscribed behavior and a subject of state intervention at the time of that ruling.

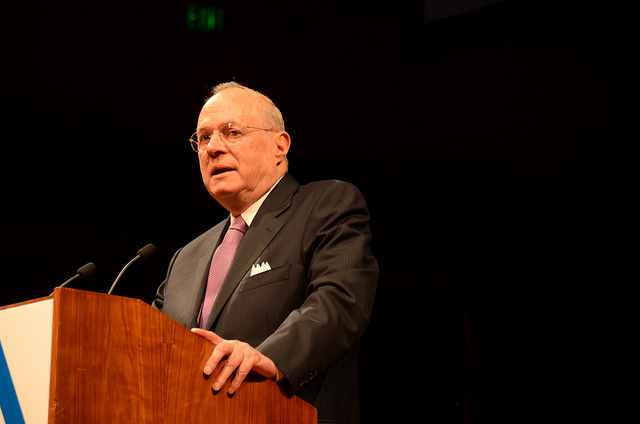

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, author of the majority opinions in Romer v. Evans, Lawrence v. Texas, and United States v. Windsor. Picture by Steve Rhodes (Flickr)

Bowers was later overturned by 2003’s Lawrence v. Texas. Since Lawrence was also a fundamental rights case, the Supreme Court did not discuss how longstanding oppression meant that a much-maligned minority was in need of greater constitutional protection, nor did it take into account the negative effects that discrimination had wreaked upon the community. Rather, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy wrote that Justices White and Burger were mistaken about what the true historical trends were at the time of the Bowers decision: “The sweeping references by Chief Justice Burger to the history of Western civilization … did not take account of other authorities pointing in an opposite direction.” As Kennedy put it, the real trend reflected “an emerging awareness that liberty gives substantial protection to adult persons in deciding how to conduct their private lives in matters pertaining to sex.” In refuting White and Burger, Justice Kennedy downplayed the history of discrimination against homosexual behavior, pointing out that sodomy laws have rarely been enforced throughout American history and that “only nine States” had imposed criminal penalties for same-sex relations.

While it may have seemed necessary to de-emphasize the history of homophobia in the United States in order to dismantle the legal reasoning behind Bowers, however, the Supreme Court has had opportunities in other cases to employ an equal protection analysis and decide whether gays and lesbians deserve heightened scrutiny as a suspect or quasi-suspect class. Even then, it has declined to clarify a proper standard of review. Justice Kennedy dodged the issue in 1996’s Romer v. Evans, saying that a Colorado law that prohibited special legal protections for gays and lesbians “neither burdens a fundamental right nor targets a suspect class.” In doing so, he threw sexual orientation into rational basis review category—which normally means that the discriminatory law would be upheld—but then added a twist by saying that if the law was motivated by “animus,” then the government would lose, even on rational basis review. Colorado’s law was thus invalidated, leading some constitutional scholars to describe the standard of review for anti-gay laws as “rational basis review with bite.” (Justice Scalia’s dissent, meanwhile, vigorously defended traditional mores against homosexuality.)

In last summer’s United States v. Windsor, Justice Kennedy—as ever, the swing vote on these issues—again played coy with the scrutiny question, even after the Obama administration announced that it would not defend the federal Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) because it believed classifications based on sexual orientation deserved heightened scrutiny. That Kennedy ultimately found DOMA unconstitutional for a somewhat confusing mélange of federalist, due process and equal protection reasons (“animus” is mentioned once in his majority opinion but not “rational basis,” and “heightened scrutiny” is used only in the context of describing the federal government’s and lower court’s position) undeniably resulted in a watershed victory for gays and lesbians. Yet the convoluted legal underpinnings behind the Romer and Windsor rulings have muddied the constitutional waters going forward. Should classifications based on sexual orientation be judged with a standard between rational basis review and intermediate scrutiny, or should courts view them in the same manner as they would gender discrimination? Are same-sex marriage bans in fact one subset of gender discrimination? With an increasing number of scientific studies showing that homosexuality is an immutable, genetic characteristic; an obvious history of discrimination; and the limited political power of the gay minority, why won’t the Court declare sexual orientation to be at least a quasi-suspect class?

In the absence of clear guidance from the Supreme Court, most of the post-Windsor rulings on marriage equality have either chosen to employ a fundamental rights analysis and held that the right to marriage includes the right to select a partner of the same sex, or played it safe with the equal protection route by following Justice Kennedy’s lead in Romer and finding that the marriage bans fail even rational basis review. This includes Judge Posner and the Seventh Circuit, who repeatedly emphasized the shameful history and “tradition” of discrimination gays and lesbians have faced, yet ultimately stopped just short of applying a heightened scrutiny standard.

A smaller number of courts have pushed even further and interpreted Windsor to mean that gays and lesbians, like women and racial minorities, deserve the protection of heightened scrutiny—a conclusion that has far-reaching implications for all laws that discriminate based on sexual orientation, not just same-sex marriage legislation. On Monday afternoon, the Ninth Circuit heard oral arguments on bans in Hawaii, Nevada and Idaho, which it seems poised to strike down using a heightened scrutiny standard, less than eight months after it deemed gays and lesbians a special protected class under the Equal Protection Clause in a juror discrimination case.

One of the lone exceptions to marriage equality’s winning streak comes from a federal judge who upheld Louisiana’s ban just last Wednesday. There, the court asserted (in the vein of Chief Justice Burger, Justice White) that same-sex marriage has never been a tradition in the United States, and that the Supreme Court has never “defined sexual orientation as a protected class, despite opportunities to do so.” Ironically, U.S. District Judge Martin Feldman invoked Loving v. Virginia in his ruling, claiming that the precedent was inapplicable to same-sex marriage because the Fourteenth Amendment explicitly condemns racial discrimination, but not sexual orientation discrimination, as unconstitutional. “The Supreme Court rightly condemned racial discrimination even though Virginia’s antimiscegenation marriage laws equally applied to both races,” he wrote. Of course, Judge Feldman was wrong about the text of the Fourteenth Amendment—it does not explicitly mention race at all. Even so, no judge in their right mind would say today that the Supreme Court was mistaken in extending greater constitutional protections to racial minorities (and to women). But not all judges have been able to connect the dots when it comes to same-sex marriage, apparently.

Such judicial opinions are, however, increasingly rare. It is incontrovertible that the tide has started to turn against those who share Judge Feldman’s beliefs. One telling moment in yesterday’s Ninth Circuit oral arguments came when Judge Stephen Reinhardt asked Deborah Ferguson, the attorney representing four Idaho couples in a lawsuit against the state’s same-sex marriage ban, if she “really care[d] whether [she would] win on the fundamental right or equal protection theory.”

No, Ferguson wisely replied.

There was a time not so long ago in history when winning on either ground would have seemed a distant dream for gay rights activists. There was a time when activists expected judges to sympathize with the oppressors rather than the abused minority when faced with the facts of the past. And there was a time not so long ago when it might have been unimaginable to see these words from a federal judge, excoriating a state for claiming that same-sex marriage is not “traditional”: “The limitation of marriage to persons of the same race was traditional in a number of states when the Supreme Court invalidated it … Tradition per se has no positive or negative significance … Tradition per se therefore cannot be a lawful ground for discrimination—regardless of the age of the tradition.” But that was then, and this is now. One can only hope that the Supreme Court is finally ready to step up to the plate and resolve this question once and for all.

·

Victoria Kwan is a Blog Editor for The Brooklyn Quarterly.

Victoria Kwan is a Blog Editor for The Brooklyn Quarterly.