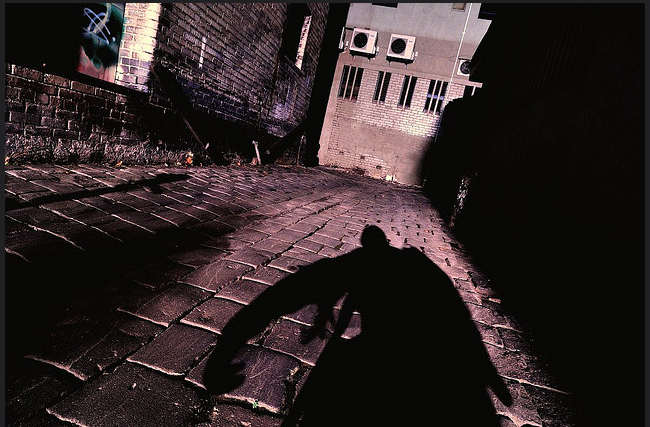

“This time last year I started plotting to kill a man. This time last year I had a gun, and a silencer, and a plan.”

Those are the opening lines of Stalking the Bogeyman, the latest theatrical production from adapter and director Markus Potter, who is not known for pulling punches. But before the audience can brand Potter’s protagonist, David Holthouse, a sociopathic criminal, the character’s motive becomes clear: he was violently raped when he was seven years old. Now he wants justice, or maybe just revenge. Either way, can we judge him?

Stalking the Bogeyman raises a series of questions about issues most people are too afraid to discuss. This, of course, is Potter’s objective—in his words, to “hold a mirror up to the darkest parts of ourselves.”

As an actor, producer, and director, Potter has spent the last two decades developing shows on and off Broadway. In each production, he aims to draw the audience into the intimacy of the theatrical experience by engaging, and sometimes unsettling, them. It is this intimacy that shatters the wall between actor and audience, forcing the audience to contend with matters of childhood rape in Stalking the Bogeyman, twenty-first century racism in Why You Beasting?, and the experience of aging in The Velocity of Autumn.

The Brooklyn Quarterly sat down recently with Potter to talk about his artistic influences—from his high school production of Brigadoon to a recent news story about a group of men who sport suits by day and wave swastika-emblazoned flags by night.

TBQ: You have spent your entire career in the arts: acting, directing, and producing. What motivated you to pursue the arts, particularly given the competitiveness of the New York landscape?

MP: I was a sports guy when I was in high school. I played football and baseball, and I started dating a girl when I was a sophomore who was in drama. And I would ask her, “what is all this about?” and I started becoming interested. She would tell me stories everyday, until finally I auditioned for a one-act play, which I was cast in.

Let’s just say I fell in love. I was going from volleyball practice to Brigadoon rehearsal. And the folks on the volleyball team didn’t like that I was doing Brigadoon rehearsals, but I ended up leaving the volleyball team to do Brigadoon and the rest was history. Just fell in love. And now, as I’ve gotten into the business and started to carve out what really interests me, I’ve found that it’s the important stories that have an effect on how we live our lives.

What kind of training did you have before you began your career as an actor and director?

I went to San Francisco State University for my BA in theater. Then I got my MFA at Columbia and studied with some titans in the theater like Anne Bogart, Kristin Linklater, and some amazing directors and teachers. That was my formal training. But really there’s no training for this career in this business. It’s just about doing it, and it’s learning on the job and being in the room with people, which really teaches you the tricks of the trade

Do you have a favorite role—actor, director, producer, or writer? Is there one that inspires you or motivates you the most?

It’s definitely director for me. I spent a lot of time acting, and I found myself not liking the plays I was auditioning for. I kept turning stuff down; I kept not loving the projects. And as a director, I have more control over picking the projects. And as an artistic director, I can pick the projects I want to work on—that is really what it came down to.

I love actors. They are incredible in what they do. I have so much respect for them. But there was something missing for me. I didn’t get that fulfillment from it. I like looking at the big picture, examining the themes and ideas behind a production. I like making the decisions of how it should look and feel, and what effect I want on an audience. And as an actor you contribute, definitely, but it’s a different experience.

What do you think is most powerful about the medium of theater?

Well there’s something obviously communal about the theater. It’s about a group of people coming together in an often-intimate space. I mean of course there’s exceptions, but generally speaking in theater there’s the act of two hundred or a thousand human beings coming together in one space at one moment in time—that’s the difference-maker for me. That’s the real humanity behind it. With film, you can hide, you can be safe, and there are usually a lot of distractions. It’s harder to be in that moment.

In discussing the inspiration behind Stalking the Bogeyman, you mention first hearing of David Holthouse’s story while listening to “This American Life.” In learning about a child’s rape, you thought of your own son, Tennessee, and how you’d react if he had been a victim of such a heinous crime. Do you select projects on the basis of what resonates with you, what touches you on a personal level?

I’m still figuring that out. But if I generalize, it’s things that really hit me in the gut, things that make me think, things that make me take a look at the world in a different way, and things that I know can make a contribution to in some artistic manner. Really it’s first a visceral reaction that I need to have. And with Stalking the Bogeyman, I absolutely had that moment. I had to pull over to the side of the road and take in the magnitude of the story. And then I just couldn’t forget about the story. The story wouldn’t leave me. I kept visualizing it, and again, coming back to my son who was one-year-old at the time and wondering what I would have done had it been my son who was violently raped.

But also, and this is important, I’m attracted to stories that keep me wanting to know what’s going to happen next. I hate being bored. I can’t stand being bored in the theater. I want to be riveted. I want to be on the edge of my seat.

You happened upon this play idea from radio, but where else do you find the inspiration for your theatrical pursuits?

Well, there’s a story that I still want to work on, but I don’t know how to yet. It’s about a subject very important to me—assisted suicide.

And I was following Jack Kevorkian, the doctor famous for assisting in many patient suicides, for example, and he and I were writing back and forth while he was in prison, and I was starting to get a piece together called Doctor Death, which then ended up becoming an HBO movie. And it’s a project that I still want to work on because I’m so passionate about the issue. And I don’t like issue-driven material, but I chase after stories I care about. I care about what’s happening in the Middle East. I want to do a story about that. So, perhaps, you’re right, it’s really about things I am personally attached to, that resonate with me.

Since Stalking the Bogeyman is your latest production—now playing at New World Stages—can you describe the process of taking the initial inspiration, scripting the play, and translating it to the stage? How long did it take? Were there any obstacles you faced along the way?

You know I had that pull-up-on-the-side-of-the-road moment with Stalking the Bogeyman. Several days after, the story was still with me so I reached out to the producers of “This American Life,” sent several notes. A few weeks later, David Holthouse, whose story Stalking the Bogeyman is based on, reached out to me and said “I’m intrigued, let’s talk.” The story had the option to be a film twice, but it never went anywhere. David had been approached by some big studios that wanted to do all of these Hollywood-type things, and he kept saying no. But I was fortunate that David liked my initial ideas about the project. So then we met in New York, had a few other meetings, and he gave me the green light.

I then started talking to a few big writers about doing the adaptation, and hit some major roadblocks with their literary agents. It was like three, four weeks would go by and I wouldn’t receive a response, so I’d have to reach out to them and say, “Hey, are you going to respond?” So I just sat down with Santino Fontana, Shane Zeigler, and Shane Stokes, and I said, “Let’s just blueprint this. Let’s just structure it as a directorial exercise. I’ll learn more about the story if we start to put it on paper somehow—still with the intention that I would bring another writer on.” And six months went by and we said, “You know we have something here.” And we decided to keep it in-house, as it were.

Once we had a script, we put together a staged reading, where you essentially invite other not-for-profit theaters, commercial producers, and people who would want to produce it or bring it somewhere. And from that reading, and with help from our producer Ian Kahn, we made the connection to the North Carolina Stage Company in Asheville. We did a production out there. We really developed the script and worked out the kinks in it. After that production we were lucky enough to get good reviews. And then, after many more rewrites of the script, we did a backers reading, an industry reading where you invite producers. From there, we assembled a team, started to find the money to put it together, and opened at New World.

So from the pull-over-the-side-of-the-road moment to opening, how long was that actual process?

That was two and half years, which is on the short side. I mean there’s are a lot of musicals out there making the rounds for five years, six, seven years, and they still haven’t opened yet. And then sometimes a theater company will say, “Hey, we’re going to pay you to write the story, and then we’re going to produce it next year.” And that can happen as well, but usually two, three years is a normal amount of time for development.

You have to be committed then. Directing is not for the faint of heart.

Definitely. I mean I worked on this piece. I’ve worked on it every day for hours and hours, all night and all morning. I mean I’ve really put my entire life into this project.

One theater critic, David Finkle, noted that the strength of your play isn’t simply revealing the horrors of sexual abuse toward a child. It’s in suggesting that, “while the victim is fathomlessly harmed, the perpetrator may also suffer at unconsidered length.” Was that your intention—to show the duality of the experience for both the victim and the perpetrator?

In Stalking the Bogeyman, the Bogeyman is the perpetrator, and we don’t learn until the end of the play what his name is. When that reveal happens, David and the audience go from viewing the rapist as a bogeyman to viewing him as a human being. We don’t know if he’s lying. We don’t know if his begging for forgiveness is sincere, but we look at him as a human being. David, in the end, calls him “a frightened, damaged man.” And it was this process—of humanizing his perpetrator—that ultimately allowed David to move forward with his life.

The reviews for Stalking the Bogeyman have been stellar, which is why I’m hardly surprised you are collaborating with David Holthouse again on a new play due out next fall. This project, in line with your other work, explores the dark sides of white supremacy. Can you tell us how you chose this as your next play?

David Holthouse is an amazing man and a brilliant writer. For several years, he worked for the Southern Poverty Law Center, and when David was going through his bout with the bogeyman, he didn’t care about his personal safety. He could care less if he lived or died, and because he was completely fearless for his own life, he put himself in extreme harm. For example, he would tattoo himself, shave his head, and go to neo-Nazi festivals to “out” white supremacists, many of whom wore suits and ties and were linked to some factions of the Tea Party. So we commissioned David to write a story based on his investigative journalism, going undercover, and exposing some of these folks. Of course, a big portion of the play will focus on another one of my pet issues—guns in America, a topic we are afraid to debate, but one that we must absolutely discuss.

So it always does come back to the smoking gun.

Yes, I suppose so. And going back to why I want to do this new play, I want to ask where are people actually having debates? I notice it on Facebook every day.

So I really want to create a vehicle, a story where you can debate intelligently that issue and converse with some authority about it. I don’t know what is going to happen or what it’s going to look like, but I’m really looking forward to seeing what David does.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

***