But these two aren’t just any women studying at elite Western universities. They are Negev Bedouin, Muslim Arab citizens of Israel whose families’ roots are planted beneath centuries of desert sand.

Though there is never a shortage of news surrounding the Gordian knot that is the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Negev Bedouin have been drifting along relatively quietly, at least to outward appearances. But in just over a century, Negev Bedouin have experienced at least three changes of national power. They’ve gone from a community of mostly nomadic herders and farmers to one whose plurality has become sedentary, living in urban settings. And they’ve gone from being mostly illiterate to achieving the highest ranks of university and professional education. The changing positions of women in these cultural crosscurrents offer valuable insight into the nuances of Bedouin life in the 21st century.

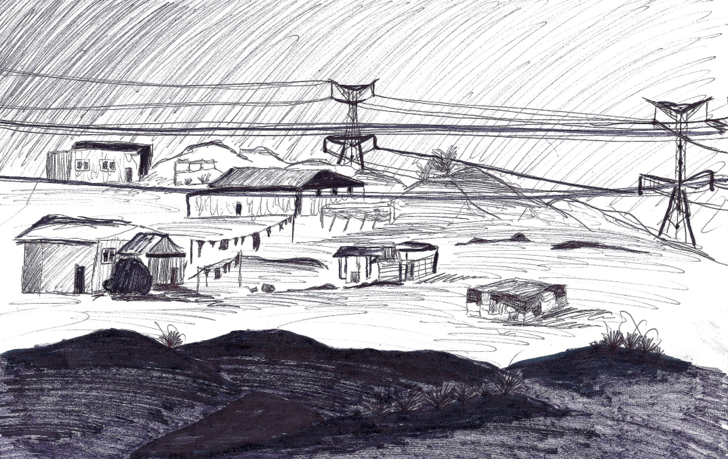

Yasmeen and Shereen offer a glimpse into the many contradictions and inconsistencies that define the lives of contemporary Negev Bedouin women. Bedouin women are at once extremely traditional, while also modernizing at breakneck pace. Some live in unrecognized settlements off the national electric and water grids; some live in urban environments. Some see Islam primarily as a political tool to distinguish themselves from secular Israeli culture; some see Islam as a vital expression of personal religious sensibilities. Some are caught in cycles of domestic violence; some advocate and advance the education of young girls and women.

Fulbright winners and Oxford students do not emerge in a vacuum; they are a product of a particular history. Forces of history, both recent and remote, are constantly at work on Negev Bedouin.

In an era in which women’s education and rights are being squashed in the name of Islamic authority, the Bedouin trajectory is worth a closer look. Higher education among the Bedouin has been rising in the last few decades, with a dramatic increase in female students. After generations of tending the home and rarely even venturing into the world un-chaperoned by husbands or male family members, newly minted academic and professional women may find their very identities are at stake. How they choose to define themselves may have profound implications for the future of their people.

“Change has to start with younger girls, and they’re caught between modern ideas and tradition.”

In the summer of 2010 Shereen Abu-Bader and Yasmeen Haj-Amer (née, Abu-Rabia’) were still undergraduate English students at Ben-Gurion University. While completing her coursework, Yasmeen was building her career in education, teaching English part-time at Ahad, an experimental Arab high school in Be’er Sheva. Her university classmates, women who ranged from their early twenties to early forties, were also pursuing careers as English teachers – the most “respectable and respected” job for women, in their estimation. No other career could offer the same type of impact within their communities, because English skills, along with better science, math, and Hebrew skills, were necessary to pursue higher education. And higher education was their ticket out of the poverty, drudgery, and violence that have long beset Bedouin society at large.

There is no singular Bedouin identity and there is no singular Bedouin experience, which makes understanding the issues they face all the more challenging. The Bedouin descend from nomadic Arab tribes, who trace their roots to the Arabian Peninsula and migrated throughout the Middle East. In Israel, the Bedouin might define themselves as any combination of Israeli, Palestinian, Bedouin, and Arab, depending on who’s answering (and who’s asking). They might also attest to strong cultural differences between southern and northern Bedouin, who arrived via different migration patterns. The term “Negev Bedouin” refers to those living in Israel’s Negev – both the Negev desert specifically, and the general southern district of Israel that begins just south of Jerusalem and extends more than 200 miles south to the Red Sea. The Negev is approximately 85 miles wide at its widest point (roughly from the southern edge of the Dead Sea to the southern tip of Gaza), and 40 miles wide at its narrowest (roughly the distance between the southwest tip of the West Bank and the northeast tip of Gaza).

Illustration by Carla Diaz

During Israel’s early years, the state needed to house the large influx of Jewish immigrants. One result was the foundation of the cities of Arad, Dimona and Yeruham as a base using Be’er Sheva, already the Negev’s capital, at the tip of this 60-square-mile rough triangle. In the early 1950s, this triangle was known as the sayig (alternatively, the siyag)- a designated geographical area inside of which Israel relocated the approximately 11,000 Negev Bedouin who remained there after the 1948 war. The rest of the approximately 70,000 Bedouin who had lived in the Negev before the founding of Israel ended up in the Egyptian Sinai, which then included Gaza, or in Jordan, which then included the West Bank.

Over the succeeding decades, immense growth in the Bedouin community coincided with a dearth of corresponding resources. By 2010, the Bedouin population had grown to more than 200,000, or about a third of the Negev’s population. About half of the Bedouin lived in unrecognized villages that did not have access to the state’s water and power grid. The other half lived in recognized towns that began to be established by the state in 1968, with the founding of Tel Sheva. The recognized Bedouin towns are generally located in or nearby the original post-’48 region, and are often interspersed among far wealthier Jewish suburbs and roads. The Bedouin town with the highest average household monthly income was, as of 2010, less than half of the average Israeli household.

In addition to economic disparity, Bedouin demographics are also quite different. While the female-to-male ratio is fairly balanced in Israel overall, there are significantly more men than women in Bedouin localities. In 2010, Bedouin women typically had seven children, compared to three or four amongst the general Israeli population. Bedouin families typically also had one primary earner. While a bigger family was advantageous, in part because it yielded more votes in local elections and therefore more political and economic clout, it could lead to major financial sacrifices and the inability to support children through extensive education.

Such imbalances limited higher education (and economic) prospects for some time, particularly among women. A handful of Negev Bedouin men attended Israeli universities in the north (and in rare cases, abroad ). However, in the mid-seventies, a push from Ben-Gurion University in Be’er Sheva to matriculate Bedouin helped spur educational aspirations. From zero Bedouin graduates in 1975, Ben-Gurion graduated thirty-one men and one woman by 1990.

A huge boost in female Bedouin matriculation at Ben-Gurion University occurred in the early 1990s, following the donation of a scholarship specifically for Bedouin women from Robert Arnow, an American financier and philanthropist, who reasoned that “the better educated the mother, the better educated the child.” By 2006, Ben-Gurion awarded bachelor degrees to 162 men and 112 women, and an increase in graduate degrees followed suit. In 1997, only 12 Bedouin had received master’s degrees – all men. By 2006, however, 96 women possessed master’s degrees.

The effects of supporting women’s education are starting to become visible in Bedouin communities, long affected by problems common to many low-income areas, chief of which being domestic violence of men against women. Where women have long suffered in silence, educated women are speaking up first.

A 2003 survey of the physical and psychosocial health of Bedouin women in the Negev, the first of its kind, found that 48 percent of respondents experienced some sort of physical violence (including being cursed, threatened, beaten, raped, kicked, or burned) in their lives, and 100 percent of them knew their attacker. The report surmised that, “the ubiquitous physical abuse is not a result of a crime but occurs in the framework of culturally engrained [sic] family violence, initially by fathers and older brothers and subsequently by spouses.”

The same study showed that the higher a woman’s education level, the more likely she was to report incidents of violence. Of uneducated women, only 22 percent reported abuse. Of women with primary school education, 38 percent reported abuse, and of women with high school education or above, 41 percent reported incidents of domestic violence.

To Shereen El-Hizayel, a social worker in Rahat with three degrees from Israeli universities, the path forward was obvious. “If we want to change society, we have to change the mother. If we can change the mother’s mentality, get her educated, she can change her attitude and stop beating kids. It’s like a circle,” she explained. “Man beats wife, wife beats children, children beat others. Change has to start with younger girls, and they’re caught between modern ideas and tradition.”

But nothing in the Middle East is ever quite so simple. Arnow’s woman-focused scholarship, while welcome throughout its decade-long term, had some unintended social consequences. Bedouin men suddenly found themselves being overtaken by newly educated women. As recently as 2011, Bedouin undergraduate women at Ben-Gurion outnumbered men 3:2. Aref Abu-Rabia’, a scholar of Bedouin history at Ben-Gurion said, “It took me ten years to convince the school to support genders equally. Because if you don’t educate the boys, who will marry the girls?”

The precariousness of Bedouin identity

“To the best of our knowledge, in modern time, no other pastoral nomadic society in Africa, the Middle East and Asia has crossed as many cultural frontier lines during a relative short span as did the Negev Bedouin in Israel,” wrote Ben-Gurion geography scholar Avinoam Meir. Not only did Bedouin society traverse “the nomadism-sedentarism-urbanism continuum” within a century, but “this society was also severed from its previous exclusive Middle Eastern Islamic-cultural environment and became a relatively isolated cultural enclave within a modern Jewish cultural environment,” Meir noted.

Sedentarization, an unwieldy term for the unwieldy process of nomads adapting to sessile life, began more than a century ago when the Ottomans realized the need for a central administrative center in southern Palestine. Shortly after establishing Be’er Sheva as a military capital in the region, the Ottomans established a tribal school in 1906 to attract sons of Bedouin sheikhs and dignitaries in the area away from sending their sons to Gaza or all the way to Istanbul. Along with formal education, the Ottomans also introduced new elements of institutional Islam – mosques, shari’a courts, and kuttabs (Islamic religious schools). Such innovations were made possible only through the advent of permanent buildings and dwellings – the first stirrings of post-nomadic life.

Before the Ottomans, the Bedouin had little use for a structure like a mosque or a school. A pre-urban Bedouin would have been educated by watching and listening to tribal elders in his father’s tents. Archaeological evidence points to minimal evidence of religious buildings and very limited religious ceremonial functions. Prayer was a mostly solitary activity occurring somewhere between the herds, tents, and desert.

Limited resources meant that Bedouin tribes were constantly fighting over the few fertile patches of the Negev. But as the Ottomans increased their military and trade presence in the Negev, tribal warfare declined, replaced by increased farming and trading opportunities in the nascent urban region. According to Aref Abu-Rabia’, the tribal school was planned as an agricultural school for Bedouin children, “where they were to have undergone change from nomads to workers of the land.”

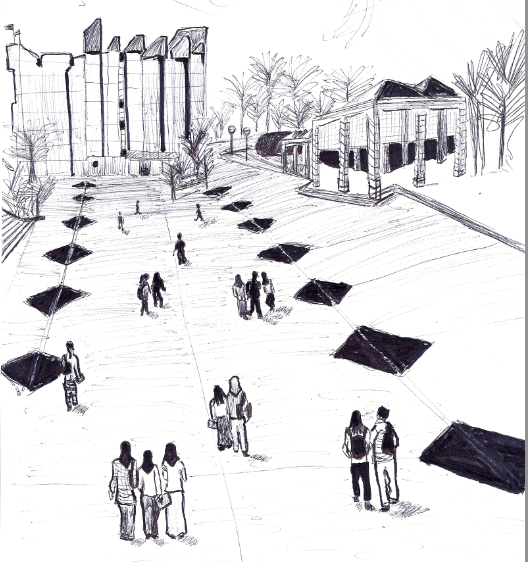

Illustration by Carla Diaz

The geographic centrality of Be’er Sheva made it an attractive location for the military and governmental purposes of the colonizing British army in World War I. Under the British Mandate, parallel education systems were formed along linguistic and ethnic lines. Arabic replaced Turkish as the language of instruction in both non-government and government sponsored schools, the latter of which included options for Muslim and Christian instruction. Education among Bedouin grew, albeit slowly, in the years leading up to 1948.

Even with the disruptions of war, economic growth and the consolidation of tribal powers drew Arabs from different backgrounds towards the city. (Aref Abu-Rabia’ noted that by 1945, most of Be’er Sheva’s population had come from Gaza or Hebron.) By the end of the British Mandate, some ninety-five Bedouin tribes had consolidated into eight confederations. After Israel was established, only three of them remained.

After Israeli independence, the state continued to implement a two-track system of Arab and Jewish secular public education (distinguished from Muslim and Jewish private religious schools). However, it devoted fewer resources to the umbrella of Arab education, which disregarded cultural differences between northern and southern Arabs, thereby reducing Bedouin distinctions further. The short-lived Ministry of Minority Affairs, followed by the Ministry of Education and Culture, printed new textbooks to replace those from the British Mandate period. In the first decade of Israel’s existence, 20 new books were prepared for Arab schools, compared with 720 books for Jewish schools. Arab schools languished in matriculation and graduation rates.

Some of the biggest discrepancies between Arab and Jewish education surfaced over language and religious instruction. Arab students were taught in Hebrew about Jewish religion, history and literature, and learned more about Judaism than Islam. As sociologist Majid Al-Haj wrote of Arab education of the era, it attempted to create “a unique Israeli Arab, one divorced from his or her original national and cultural roots, which are closely connected with the Arab world and Palestinians.”

Though the 1970s and ’80s saw significant education reforms for Arab schools, problems persisted. The history curriculum in Arab schools allowed for the optional mention of “the Arab nation” and its affiliation with Islam, but without specific reference to Palestinians, or Bedouin for that matter. Meanwhile, the scope of Jewish history within Arab school curricula expanded. Among the endless consequences of maintaining linguistically and religiously separate public school systems, one result was the embedding of Bedouin history and identity within either a vague “Arab” history or a specific “Palestinian” history – neither of which quite fits the reality. Here, scare quotes do not imply illegitimacy of either term, but rather connote the fraught nature of choosing labels in Israel, and the unique challenges faced by those who would still identify themselves as Bedouin. The ambiguity and confusion are compounded by the geographic distribution of families, commerce, and culture across borders. Between 1967 and the first Palestinian Intifada beginning in 1987, travel was mostly open throughout the Negev, including Gaza and the West Bank. As the Bedouin increasingly settled over the century, mosques and other symbols of established Islam permeated the cultural sphere, replacing certain aspects of traditional Bedouin ritual and law.

Islamic infrastructure spills into the streets, literally. Rahat, the largest of the Bedouin towns, is full of street signs that don’t offer the name of the street, but instead read, “By the grace of God” and “God is merciful” and other common Arabic and Islamic sayings. Such signposts of Islam literally and figuratively fill the cultural void left by the loss of nomadic tradition; Islam creates a banner that transcends the fluctuating borders and nationalities of a miniscule region. For some, particularly among the more than 60 percent of the Bedouin population that is under 25 years old, growing Islamic identity can dovetail with a growing affinity with Palestinians.

Shereen El-Hizayel found that the concentrated nature of city life, along with events such as the Iraq War and the Gaza War in 2008, have led the students she’s worked with to identify more with Palestinians and become more religious. Similarly, over the years, she has assigned herself a rigorous Islamic curriculum, and quotes the Qur’an and Islamic scholars such as al-Ghazali, and Ibn Taymiyya with ease. She sees her world pretty clearly: “I’m a Muslim first, then Palestinian, then Bedouin,” she said. “Israel is what’s on my passport but that’s it,” she said.

If the state can’t figure out how to work with its Bedouin citizens to their mutual benefit and development, it risks losing control of the Negev. “Because of the birthrate, the Negev will look like the slums of Brazil if the state does not deal with the Bedouins quickly,” said Uri Mintzker, who studied rural Bedouin at Ben-Gurion. The state doles out social security based on the number of children in a family – a policy that is meant to support large ultra-Orthodox Jewish families with high unemployment. But Bedouin families also benefit from this system. While the practice of multiple wives is technically illegal in Israel, all children still qualify for social security checks, including children by second and third wives. “It’s a way to make money off the state,” he said. “The state is weak on polygamy because relevant authorities don’t want to get involved. It’s bad for the state and bad for women.”

As a result of more than a century of ambiguous educational frameworks coupled with (or reflecting) political and geographic chaos, high birthrates, and external coercion toward a standardized Islam, Bedouin identity hangs precariously. It is a Sword of Damocles (albeit perhaps one of many) that dangles over Israel’s future, and no one is looking up.

“We are not so separate anymore.”

It has taken generations for women (and men) to begin to overcome the types of challenges that face Bedouin society. Shereen Abu-Bader’s grandmother Aisha, for example, never learned to read. Born soon after the dawn of Israeli statehood, Aisha never went to school since there were no roads or buses to bring her there. She never learned much Hebrew, either, which meant further isolation from the state around her. Aisha married and became a second wife at 14 after her father told her it had been arranged. She didn’t have much of an opinion on getting married, even to a man who already had a wife. It was fairly normal practice, and the family eventually moved to the newly established town of Laqiya. The wives helped raise each other’s children, and only seldom did their husband’s alternating sleeping schedule cause any problems. She educated herself a little over the years, learning the Qur’an by heart from cassettes, and going on the hajj 13 years ago.

Meanwhile, Suleiman Abu-Bader, Shereen’s father, belongs to a generation of Bedouin men who began to take advantage of expanded educational opportunities both at home and abroad for himself and his family. After receiving a B.A. in math and statistics from Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Suleiman later pursued an M.A. in Economics from Ben-Gurion University, followed by a Ph.D. in Economics at Cornell University. After he received his Ph.D., Suleiman became a professor at Ben-Gurion, and continued to make educational advancement for Bedouin a priority, contributing to the Center for Bedouin Studies and assisting the Bedouin Academic Association. He also sent his daughters to the Jewish high school adjacent to Laqiya, knowing it would better serve their academic needs.

Formal Hebrew language instruction typically begins in third grade in Arab secular schools, and is used as the language of instruction in about half the subjects in high school. Since the language spoken at home is exclusively Arabic, it puts Bedouin students at a distinct disadvantage to their Jewish Israeli neighbors should they try to enroll in Israeli universities, where just about everything is communicated in Hebrew.

Illustration by Carla Diaz

While language is of primary concern, it is far from the only cross-cultural hurdle Bedouin students face. Equally important is preparing Bedouin students for university culture, in which family pedigree has little or no meaning. Many Bedouin schools suffer from nepotism, where bigger families are in control of the smaller ones and towns are divided by tribe. Having the political power to be a mayor or council member of a Bedouin town allows a family to allocate jobs such as teachers or school headmasters, or even exert control over where a new school might be built and who gets to build it. This kind of unchecked internal system is one reason why Bedouin schools consistently yield higher dropout rates and lower university matriculation rates than Jewish schools.

Until recently, Jewish schools were the only serious option for Bedouin families who wanted their children to learn enough Hebrew and English to function in an Israeli university setting. In the last 20 years, this has become a semi-common recourse for the children of educated fathers, especially those with Jewish colleagues. But better education came at a price. Jewish schools inevitably left students with weaker Arabic skills and without Islamic instruction to parallel their Jewish courses, not to mention fewer social ties to Bedouin peers.

This was the case for Shereen, who, between the ages of four and nine, lived in Ithaca, N.Y. with her family during her father’s stretch at Cornell. While Shereen’s older sister had a firm grasp of Arabic before the family’s American sojourn and her three younger brothers only remember life in Israel, Shereen’s first language is English. Going to Jewish school meant that her second language became Hebrew. Her Arabic, especially the dialect among Negev Bedouin, floundered.

Though Shereen’s background positioned her to excel in university life, this kind of tradeoff between good education and strong cultural heritage became increasingly worrisome to Bedouin parents. One solution arrived in 2009 with the creation of Beit HaSefer Ahad L’Meda’im. Known as Ahad, it was the first private high school established expressly for and by Arabs in southern Israel. The need for a school that could prepare Bedouin youth for the rigors of Israeli university also intensified as more pharmaceutical and technology companies began expanding into the Negev, bringing well-paying specialized jobs with them.

Initially, that meant recognizing the need for more English and science instruction. But those familiar with Israeli universities knew that it would be equally important to prepare Bedouin students for meritocratic university culture, which can often come as a shock. At Ahad, having a lab partner – or a teacher – from a different tribe or town often helps break down pre-existing biases. Like Yasmeen Abu-Rabia’.

Yasmeen’s students teased her early on for her “funny accent” – a giveaway that she was not from one of the main Bedouin towns. Yasmeen’s village, Drijat, was unrecognized by the state until 2004 and as a result faced the real threat of demolition. Growing up as the daughter of the artist Bashir Abu-Rabia’ (painter and special effects producer for the critically acclaimed 2009 film “Ajami”) Yasmeen remembers doing much of her childhood homework in the few hours of the evening before the electric generators ran out. But as far as her students were concerned, she was simply from Drijat, known historically as a fellaheen village, populated by a class of Arabs who once worked the lands of the more powerful “real Bedouin” clans. The mere presence of Yasmeen in a position of authority forced her students, even subconsciously, to begin to confront and break down stereotypes.

Salem Abod, a co-founder of Ahad who had previously sent his daughter to a Jewish high school, felt a special responsibility towards educating girls. Although Ahad mixed boys and girls in classes, girls were still at an acute disadvantage. While the existence of the school indicated parental support for investing in education, parents and family members still had to be convinced that it was morally acceptable for girls to go to school. And while the girls were aware of the significance of their parents’ support, they had to work hard to become confident to participate in the classroom. Stereotypes were often leveled at girls in general, whose education was still frequently seen in 2010 as superfluous, at best.

Illustration by Carla Diaz

Salem especially wanted Ahad to encourage girls to study engineering and the sciences from an early age, so that they could reach master’s and doctorate levels later on. “Why just be an elementary school teacher?” he said. “[Parents] know that life for Bedouin women is moving with each generation. No more sheep and fields for them.”

But teaching will likely remain a top career choice for a while, in part because it’s respected, and in part because it’s relatively safe. Yasmeen’s friend Amira, for example, had studied mathematics at Birzeit University, near Ramallah in the West Bank, but married before she finished her degree. At first she was apprehensive about joining the Bedouin world; 20 years ago society was quite different. Bedouin society was even more notorious back then for domestic abuse, unemployment, lack of education, and other ailments of poverty. Her father, who worked in Be’er Sheva, chose her husband for her and she entered a world where women rarely left their homes and then only went short distances if they ventured out.

After years of staying home and taking care of her five children, Amira started an informal kindergarten in the early 2000s. That inspired her to go back to school for a degree so she could teach high school English. Though it took a little coaxing, Amira’s husband eventually supported her decision. “Before now, the only work women had was having babies,” Amira said. “But this changed. We see more. We get exposure through TV and work, in the hospitals, in the university. We are not so separate anymore.”

“I live within a label – all of these labels… I love being a person, without being a ‘Bedouin’ or ‘Israeli.’”

Higher education among Bedouin women has undoubtedly increased their inclusion into modern Western life, but it has not been easy. Women who choose to advance their academic and professional lives are expected to continually prove to their communities that they are intellectually and morally worthy of their ambition. For Yasmeen and Shereen, studying abroad – for all its own challenges – is a welcome respite.

“This is like a break,” Yasmeen said of her current Oxford program. “It’s an international course – it’s fantastic. It’s not like in Israel, with just Israeli and Arab students. It’s all these different cultures and different students.” Yasmeen, whose classmates, who hail from the U.K., Saudia Arabia, Oman, Japan, China, and South Korea, added, “[My students] need English as an international language, to come in contact with other cultures.”

Yasmeen’s definition of a break boggles the mind a little. With her husband and almost two-year-old son in tow, she’s completing a dissertation on the semantic and political challenges Arab students face when studying English. In May, she and her family will return to Drijat. She’ll resume teaching high school English in the nearby town of Kuseife. She’ll also finish her third year of her other master’s degree in English Literature at Ben-Gurion University. She’s hoping her new Oxford degree will afford her some more respect when dealing with the administrators at her school, who she says have intermittently suggested that she help her students cheat on the state’s standardized exams. They have also disapproved of an English language magazine she created to feature her female students’ writing.

For Shereen, the break that a Fulbright promises is more existential. Currently a high school English teacher as well, she spent a recent semester in the Czech Republic, and has had a taste of what to look forward to. “I had a lot of freedom over there,” she said. “Studying abroad made me think a lot about who I want to be. Living in Israel, you don’t think of yourself as an individual, I think of myself as a Bedouin, or Muslim, or Israeli. I live within a label – all of these labels. It’s amazing to have the freedom of what to think and what to believe. I love being a person, without being a ‘Bedouin’ or ‘Israeli.’”

At the same time, she knows how rare her circumstances are. Even though she “didn’t have to answer to anyone” in Prague, she was very disciplined. “Most girls, their parents don’t give them the opportunity to leave. I owe a lot to my parents and family that they let me go. I didn’t want to go off and ruin it,” she said. “It’s really important to show that a girl can go abroad and still be herself and not be completely transformed, to show that a girl can travel without being influenced, and won’t forget her religion or society.”

If religion has become clearer, society has become murkier. After generations of seismic changes reverberating through the Negev, one is left wondering: Who is still a Bedouin?

“An Arab in Be’er Sheva has more common with a Bedouin Arab in an unrecognized village than with an Arab in Haifa,” Yasmeen said. “The ‘Bedouins’ are no longer, not post ’48, not really. ‘Bedouins’ just means Southern Arabs.”

And according to Aref Abu-Rabia’, “The Bedouin is a desert dweller. The Bedouin are Arabs by nationality, Muslims by religion, belong to the Semitic race, and are descendants of Ishmael and Abraham.” By these definitions, the Bedouin, swept up in the dust storm of urbanization, education, and Islamization, is nearly extinct.

Nearly, but not quite. There may not be much left, but something compels Shereen and Yasmeen to plan to return to their homes and families, once their trips are over. There is work to be done. Yasmeen is committed to using English to expose her students “not just to Western culture, but world culture.” Shereen, for her part, is passionate about getting through to teenage girls that “they can do other stuff” besides get engaged by 16.

Equipped with some of the most diverse international perspectives that have ever penetrated Bedouin culture, these women (and others like them), have the potential to shape the future trajectory of Bedouin legacy in ways previously unimaginable. Their generation is unprecedented in its open-mindedness, global exposure, academic and professional resources, and freedom to enact change in their community. The world would do well to watch.

•

Elissa Lerner is a senior editor at The Brooklyn Quarterly. She was previously the Clay Felker Fellow at Duke Magazine, and her work has been published in the literary blog of The New Yorker, The New Inquiry, and ESPN the Magazine, among others. Her full-length play, Abraham’s Daughters, was produced in the New York International Fringe Festival. For more of her work, visit elissalerner.com.

Elissa Lerner is a senior editor at The Brooklyn Quarterly. She was previously the Clay Felker Fellow at Duke Magazine, and her work has been published in the literary blog of The New Yorker, The New Inquiry, and ESPN the Magazine, among others. Her full-length play, Abraham’s Daughters, was produced in the New York International Fringe Festival. For more of her work, visit elissalerner.com.