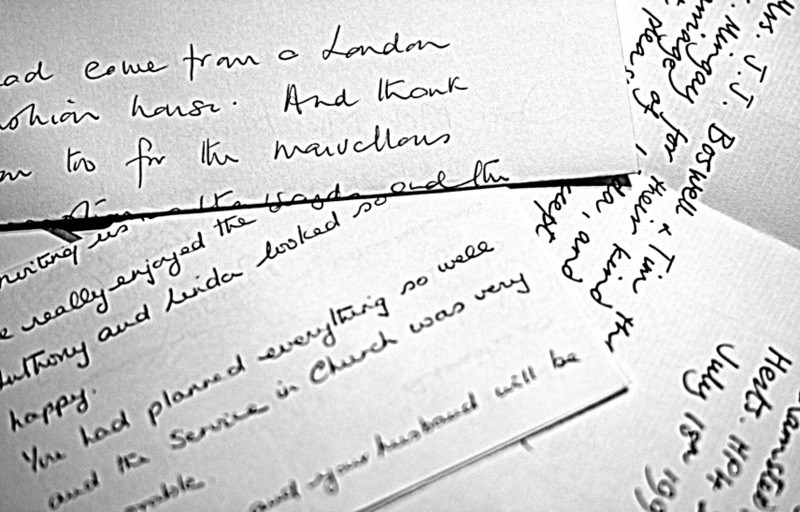

Letter-writing provides the world with an archaic, yet historically vital, link to the past. Maurice Mingay / Flickr

Whenever a form of writing dies, something is lost. The handwritten letter is an art form, a genre of writing, a means of communication, and an access point to history. Most of us aren’t writing them anymore—certainly not as our primary means of communication. We have given letter writing up in favor of the variety, celerity, and efficiency that contemporary modes of communication have to offer. What are the consequences of letter writing fading away?

More than just lamenting the death of letter writing out of nostalgic sentimentality, or trying to eulogize it or bring about its revival, what is most lamentable is the loss of a specific type of documentary record—a mode of communication that wields specific authority as artifact. Even when we know, or think we know, the whole story, letters invite new insights, perspectives, and ways of thinking about major historical events.

Through the information they contain, and the manner in which it is conveyed, letters from the past can conjure up the general atmosphere and social climate of another time and place, and reveal what was vital and integral to a culture. In correspondences with friends and family, people communicated details about historical events when they were still a part of everyday life. These letters contain information that we might find in the “Talk of the Town” or “A Reporter at Large” section of The New Yorker—except they’re addressed to a specific somebody, and for the most part, were not intended for publication.

On May 13, 1846, President James K. Polk proclaimed war between Mexico and the United States. On May 29, Herman Melville wrote to his brother Gansevoort, who was residing in London:

People here are all in a state of delirium about the Mexican War. A military order pervades all ranks—Militia Colonels wax red in their coat facings—and ’prenticeboys are running off to the wars by scores.—Nothing is talked of but the “Halls of the Montezumas.” And to hear folks prate about the purely figurative apartments one would suppose that they were another Versailles where our democratic rabble meant to “make a night of it“ ere long.—The redoubtable General Viele “went off” in a violent war paroxysm to Washington the other day. His object is to get a commission for raising volunteers about here & taking the field at their head next fall.—

Unknown to Melville at the time, he was writing to a dead man. Gansevoort had died of brain disease on May 12—more than two weeks before Melville sat down to pen the letter in Lansingburgh, NY, and a day before the war was declared. Writing as if his brother were still alive, Melville chronicled the atmospheric tensions and uncertainties in America as events unfolded: the sights, the sounds, the weather, and the people’s reactions. Evaluation and judgment, if any, would come later. In the moment of writing the letter, Melville conveys to his brother how he himself felt about the proclamation of War. “But seriously something great is impending,” he writes, adding that

The Mexican War (tho’ our troops have behaved right well) is nothing of itself—but “a little spark kindleth a great fire” as the well known author of the Proverbs very justly remarks—and who knows what all this may lead to— Will it provoke a war with England? Or any other great power?—Prithee, are there any notable battles in store—any Yankee Waterloos?—or think once of a mighty Yankee fleet coming to the war shock in the middle of the A[t]lantic with an English one.—Lord, the day is at hand, when we will be able to talk of our killed & wounded like some of the old Eastern conquerors reckoning them up by thousands;—when the Battle of Monmouth will be thought child’s play—& canes made out of the Constitution’s timbers be thought no more of than bamboos.—I am at the end of my sheet—God bless you My Dear Gansevoort & bring you to your feet again.

The letter evokes the pervading sense of doubt, confusion, and uneasiness that his compatriots felt. Here we have a documentary record that exists because the nineteenth-century means of communication lacked the many options and speed that we have today. Had Melville been able to receive a text message or email of sorts containing news of his brother’s death, he probably would not have written this letter, in which he furnishes Gansevoort—and us—with a description of what it was like to be in America at the onset of the Spanish-American War.

Letters from the past offer us a way to get closer to a person from the past, someone whose artistic genius we admire but who is no longer alive. The handwritten aspect is one thing, but there’s also the content that follows form. I exult over Melville’s letters, page after page, letter after letter. I’ve realized that he has illegible handwriting and horrendous spelling, however, and have since switched to reading the transcribed versions of his correspondences. Transcribed or not, the contents of these letters continue to reveal things about its writer, his life, his times, and who he was as a person. Through them, we get the sense that Melville was pretty obsessed with Nathaniel Hawthorne. “Whence come you, Hawthorne?” he pined in a letter dated November 17, 1851, just a few days after Moby-Dick had been published in the United States. He tells Hawthorne in that same letter: “But with you for a passenger, I am content and can be happy. I shall leave the world, I feel, with more satisfaction for having come to know you. Knowing you persuades me more than the Bible of our immortality.” He ends the letter and signs off, but isn’t quite ready to say goodbye:

P.S. I can’t stop yet. If the world was entirely made up of Magians, I’ll tell you what I should do. I should have a paper-mill established at one end of the house, and so have an endless riband of foolscaps rolling in upon the desk; and upon that endless riband I should write a thousand million—billion thoughts, all under the form of a letter to you. The divine magnet is in you, and my magnet responds. Which is the biggest? A foolish question—they are One.

Besides these affectionate effusions and waves of thought, Melville’s correspondences over time also reveal the development and exchange of ideas between the two authors, as well as the progression of their friendship. In August 1852, Melville gives Hawthorne his idea for a story about a woman called Agatha Hatch, thinking that it “lies very much in a vein, with which [Hawthorne] is familiar,” and in this manner “would make a better hand at it” than Melville would, and encloses with the letter his notes for the whole story. Hawthorne, however, “expressed uncertainty” concerning “undertaking the story of Agatha,” and instead urged Melville to write it.

Melville also occasionally fantasized about Shakespeare promenading on Broadway and Astor Place:

I would to God Shakspeare had lived later, & promenaded in Broadway. Not that I might have had the pleasure of leaving my card for him at the Astor, or made merry with him over a bowl of the fine Duyckinck punch; but that the muzzle which all men wore on their souls in the Elizabethan day, might not have intercepted Shakspers full articulations.

The autobiographical elements of the letters provide us with a glimpse into Melville’s 19th-century world, the New York City that he knew, and the literary circles of the period. We know from his letters to publisher and friend Evert A. Duyckinck that Melville attended Ralph Waldo Emerson’s lectures and thought him “a brilliant fellow.” Given the lack of correspondence between Melville and Walt Whitman, we might also guess that they probably never met each other, despite being born in the same year, having lived in relatively close proximity to one another, and dying just one year apart.

In his letters Melville often talked about book sales, critical reception of his books, up and coming works, costs involved in publishing and copyrights, etc. We see how the readers’ expectations are taken into consideration, and how they might have influenced the literary productions of the day.

Viewing these letters in sequence and in context with a writer’s works provides another window into the mind that created them, as well as its influences. The idea of the death of the author is a familiar one, but clearly people are still interested in the authorial voices and artistic minds behind creative works. Consider the popularity of Shaun Usher’s blog, Letters of Note, and the enduring presence of interviews with authors and artists in magazine publications such as The Paris Review and Interview Magazine. On view last year at the Dan Flavin Art Institute in Bridgehampton, NY are Carl Andre’s handwritten correspondences with Sol Lewitt. Recently, Princeton University Press published a compilation of artist correspondences, many of which contained drawings, doodles, and other artistic creations. Letters invite new insights and perspectives on their writers, their lives, their works, and historical events. They also give us the opportunity to trace relationships between principle figures from the past, and track the development of ideas as well as literary and artistic practices.

Reading epistolary accounts of historical events transports us to another time and place, and causes the events to resonate more deeply. The immediacy that we find in letters arises from them being written in a much slower-paced world, before communication had dwindled into peremptory phrases and fragments of thought, delivered with the click of a mouse or a tap on a screen. It also arises out of necessity, perhaps, since there weren’t many other options for communicating with someone. Delivery of these letters is not always guaranteed, but people still wrote lengthy thoughtful letters anyway because it’s not like they had many other options. The letter allows the incisive communication of matters—both historical and personal— at the same time that it lends itself to the philosophical ramblings, inadvertent reflections, and cascading streams of consciousness that emerge as the writer dashes his voice against the quiet sheet of paper. Letter writing may not be the most efficient way to communicate these days, but its disappearance means the loss of a specific type of documentary record: one that not only allows us to get closer to someone from the past, but also is in itself resonant with history.