What is the role of art in shaping public policy and fostering political change? Artist Laurie Jo Reynolds describes her work as “legislative art”—art that engages government systems with the goal to accomplish concrete political change. Much of this work stems from a belief that emerged in her years as a public policy major, that reforms to American systems of education and incarceration were (and still are) urgently needed. In 2007, Reynolds collaborated with currently and formerly incarcerated persons, their families and other artists to launch the Tamms Year Ten project, a volunteer grassroots legislative campaign to reform or close the Tamms Correctional Center, which housed a supermax prison in southern Illinois designed that was specifically for sensory deprivation accomplished through near-constant solitary confinement. Tamms Year Ten had many components, notably intensive lobbying and cultural projects like “Photo Requests from Solitary,” which invited prisoners in isolation to request an image of anything at all, real or imagined. In part as a direct result of the multiple approaches deployed in this “legislative art,” Illinois Governor Pat Quinn closed Tamms in January 2013.

At the recent Creative Time Summit, held at NYU’s Skirball Center on October 25-26, Reynolds was a co-recipient (along with Khaled Hourani) of the 2013 Leonore Annenberg Prize for Art and Social Change. In accepting this award, Reynolds elaborated on what she means by legislative art; in her approach, “legislative art” is a creative practice that recognizes “no distinction between art and politics.” She also refused to accept the award alone; with her were Brenda Townsend, mother of a former Tamms inmate; Reginald “Akkeem” Berry, a former inmate; and Darrell Cannon, a former inmate who spent nine years in solitary confinement. In her remarks, Reynolds emphasized that legislative art “does not permit just putting information out into the ether. Action is required… yay spreadsheets!” After an onstage discussion led by former musician John Forte, whose mandatory 14-year sentence on federal drug charges was commuted by President Bush in 2008, the house lights came up and Reynolds asked the audience to remain in their seats, for “a moment of endurance.” Reynolds left the stage, but Townsend, Berry and Cannon remained, each standing in silence one minute for each year they (with Townsend standing on behalf of her son, who is still incarcerated) had spent in solitary confinement at Tamms.

Someone dimmed the house lights; as silence thickened around us, the air grew colder and more still. The only movement seemed to be the dust mites in the stage lights focused on Townsend, Berry and Cannon and the small changes in posture as they shifted weight from one foot to the other, heads bowed. Slowly, as the seconds elapsed, I became aware of noises from the audience; first the unmistakable sniffing back of tears and next a murmur of whispers a few rows behind me. Just as the whispering grew louder and someone uttered a sharp, outraged “Shhhh!”—six people in the front section of the auditorium stood up. And then a few more. And so on, until a good half of the audience stood facing the three onstage. Townsend was crying where she stood. The man seated next to me, who had been making watercolor sketches of the proceedings using a plastic miniature palette, had tears streaming down his face as well. I stood but did not cry; the truth of this “moment of endurance” was too dark, too real, too not mine. Berry departed the stage first, then Cannon; Townsend was there alone for what felt like hours, 14 minutes in all for each of the years her son lived in solitary confinement.

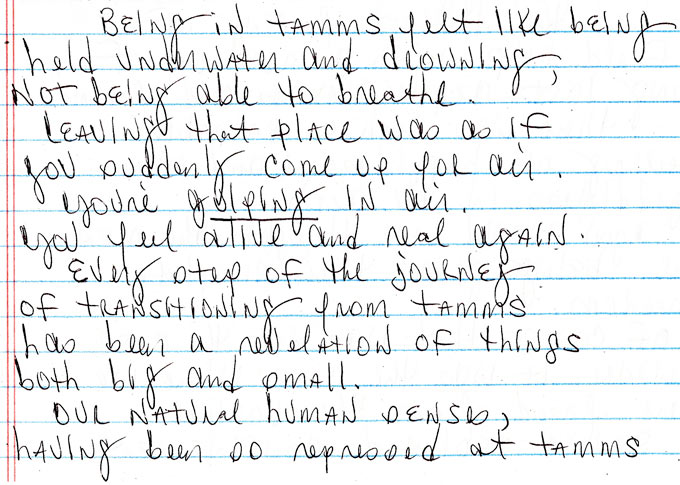

Reporting for KQED , Christian Frock described the scene as “not an artwork per se,” but in noting the compassion and empathy displayed by the audience, claimed that the “experience embodied art at its most compelling.” While this moment of unscripted art was undeniably profound for many in attendance, it also had its critics, both at the summit and among those following the action on Twitter. For some, the very idea of hosting a gathering devoted to art and social activism in a space as walled-off from the general public as NYU seemed paradoxical at best. For others, the “moment of endurance” itself raised questions: whose endurance mattered here? Did we, the privileged members of the New York art world and the press, really have the right to participate? Could anyone really say we were weeping with them and not at them? These critics have a point. Perhaps the only one of us who can claim to be weeping with them is Laurie Jo Reynolds, because she has worked alongside them. As for this writer, the scene brought to mind the power of witness and the danger in offering emotional solidarity with someone else’s suffering without mindful (and active) awareness of differences between us. When witness occurs without this awareness, we run the risk of replicating Harriet Beecher Stowe’s admonition in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, that we are simply called upon to “feel right”—in this case about torture, sensory deprivation, family trauma. As Reynolds’ concept of “legislative art” spells out, surely we are called upon to do more in a country founded on freedom that has thousands upon thousands in longer-term solitary confinement, a state that doctors say compromises mental health and human rights advocates classify as torture.

What matters most is that Reynolds herself was not out on that stage. Having not experienced solitary confinement, she did not seek to perform an act of solidarity that could ring false. Whether or not you believe that lobbying can be called art, this “moment of endurance” captured the beauty of a creative process that uses visual aesthetics to express a powerful cry of protest. We in the audience were witnesses; whether or not any of us will earn the right to claim solidarity is an open question.