A cosmetics class in 1950. How times have changed. Wikimedia Commons

Whether or not you watch Comedy Central’s Inside Amy Schumer, or even know who Amy Schumer is, it is likely you have seen the sketch from her show, “Girl, You don’t Need Make-up,” shared by your friends on Twitter or Facebook.

In the sketch, Schumer, looking dolled up, runs into four boys from a boy band singing to her that she doesn’t need all that make-up on to be beautiful. They tell her to go and wash it off. The band is a parody of One Direction and the song they are singing at Schumer is a satirical send up of the group’s song “You Don’t Know You’re Beautiful” where the five boys croon to an anonymous young woman unaware of her beauty that she doesn’t need “make-up to cover up, being the way that [she] is enough.”

In Schumer’s sketch, she gives into the boys’ pleas and washes her make-up off. When she emerges, sans make-up, the boys realize they’ve made a terrible mistake—Shumer’s “lashes are so stubby and pale”—and she in fact does need to “get up an hour earlier to look much girlier.”

The response to the sketch on the night it aired, goaded by Schumer herself, was immense. Thousands of women tweeted photos of themselves with the hashtag #girlyoudontneednomakeup, proudly sharing photos of themselves without cosmetics. In response, Schumer retweeted hundreds of these replies and chatted with many of the tweeters, bringing together a large community of women who, if only momentarily, connected with each other regarding the standards of beauty they are expected to meet.

And Schumer seemed genuinely moved:

I have been brought to tears with all the strong, badass, incredible women tonight. In jungles, jumping out of planes, holding their babies

— Amy Schumer (@amyschumer) April 29, 2015

Schumer has been instrumental as a comedian who explicitly acknowledges the impossible standards to which all women, but especially those in television and film, are held. In another sketch from Inside Amy Schumer, she sits around a table with Julia Louis Dreyfus, Tina Fey, and Patricia Arquette to celebrate Julia Louis Dreyfus’ “Last Fuckable Day.” When Schumer looks perplexed, Dreyfus tells her that, “in every actress’s life the media decide when you finally reach the point when you’re not believably fuckable anymore.” The women then explain to Schumer the telltale signs that your fuckability is over. Through her absurdist comedy, Schumer draws out illogical beauty standards, all of which have meaningful and substantial effects on the lives of millions of women. Women in television and movies have fewer roles for which they can audition as they get older. Women comprise about 37 percent of prime-time TV characters, and of those characters, only 15 percent are 45 years of age or older. Responding to this trend, many actors try to maintain their careers by resort to painful and expensive plastic surgery that they, in the case of Portia de Rossi, Meg Ryan, and Jennifer Gray, are then criticized for. Yet regardless of the degree to which a woman’s appearance is critical to her career, the way she looks is still scrutinized. As a First Lady, Secretary of State, and a presidential candidate, Hillary Clinton’s appearance has been analyzed and criticized. Forbes described a trip by Clinton to the United Nations General Assembly as a “Hair Clip Controversy,” as if this was the most important aspect of her meeting. The article addresses those who suggest a woman’s appearance in this setting should not matter, but argued:

“Clinton is a public figure, and as with any public figure she must dress the part–and dress professionally. She was meeting with many important global leaders to speak about very important issues such as offering support to Pakistan and Haiti. Her less-than-perfect hair was not the issue, it was that she adorned it with a silver butterfly clip–an accessory most commonly worn by middle- and high-school girls. The accessory lacked the gravitas required of the event and of the topics Clinton was there to discuss. Can you imagine if President Barack Obama showed up for a meeting with a clip-on bowtie? Or with brightly colored sneakers?”

The Forbes article noted the accessory worn by Clinton at the UN General Assembly lacked gravitas, as if an appropriate hair accessory that projects gravitas exists. This comment reflects the impossible dilemma a woman in politics faces, which is to appear appropriately feminine, because she is female, but masculine enough to be wield political power and influence. Yet many women do not keep up with fashion trends, and for Clinton the hair clip was likely to have been selected on the basis of function, instead of fashion. Furthermore, it is reasonable to prefer that those in positions of power be more interested in the duties of their high power positions, than maintaining a particular style. Certainly Clinton could hire people to ensure she keeps up with fashion trends, but this would put her at risk of being criticized for wasting money, or being a “diva.” For example, when it was discovered that Republic National Committee funds had been invested in provided then Vice Presidential nominee Sarah Palin with a new wardrobe during the 2008 election, the media response was a feeding frenzy. Politico, Vanity Fair, The Huffington Post, ABC News, The New York Times, People, and The Telegraph all filed reports. The onslaught of media attention on the appearances of women in politics is now so routine, that during this year’s White House Correspondent’s Dinner, comedian and host Cecily Strong raised her right hand, asked the audience to do so as well, and announced, “repeat after me: ‘I solemnly swear… to not talk about Hillary’s appearance… because that is not journalism.’”

ICYMI: Cecily Strong made WH press swear not to talk about Hillary’s appearance “because that is not journalism.” http://t.co/kUdDxJxA5s

— NowThis (@nowthisnews) April 27, 2015

Women who are not actors or politicians are also subjected to very narrow notions of beauty, and are just as susceptible to their impact. While many women do not have careers that directly rely on their physical appearance, the pressure to look a certain way affects them, and leads many young girls and women to develop eating disorders and low self-esteem. Since 1997, cosmetic procedures performed on women under the age of 19 have tripled. Furthermore, The National Institute of Mental Health estimates that eating disorders affect more than five million Americans, 90 percent of whom are women. This is the reality of an environment where women are valued on the basis of their physical appearance.

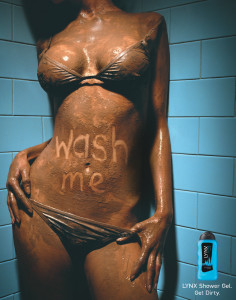

Dr. Caroline Heldman, Professor of Politics at Occidental College, has done substantial research and has given numerous lectures on sexual objectification, analyzing the practice of media portraying women as objects, where only parts of their bodies are pictured, and their sexual availability is their defining characteristic. For example, in this advertisement for LYNX shower gel, a women’s midsection is the subject of the ad, but by removing her head and face she is dehumanized. Moreover, the “wash me” writing on her stomach suggests her body could very well be replaced with that of a dirty car.

Most dangerously, women that see their self-worth as being tied to their physical appearance are less politically and civically engaged. It should then come as no surprise that our political institutions are predominantly male; even with all of the progress women have made in the past century, only 20 percent of United States Congressional representatives are women. And Clinton’s, and well as Palin’s, high-profile experiences as political women in the limelight is likely to further discourage women from running for office.

In fact, while there are a number of factors that contribute to women’s underrepresentation government, new research suggests that women do not want to run. This “ambition gap” can be traced back to the means by which we raise our young girls, and the degree to which we emphasize that their contribution to society is grounded within their physical appearance.

American University Political Scientist Jennifer Lawless and Loyola Marymount University Political Scientist Richard L. Fox published a report that found young men, more than young women, are socialized by their parents to consider political careers. This is then accompanied by disparities in political discussion, exposure to information, and encouragement. There are a number of traps that parents fall into when raising young girls that correlate to the ambition gap, such as telling them to be quiet and polite while letting young boys run amok. These gestures signal to young girls that they shouldn’t stand up for what they deserve, or speak up when they have something to say. Gendered toys for girls prize appearance and beauty over being active or competitive. Competition in particular is a key factor, according to Lawless and Fox, in predicting whether a woman will have political ambitions. Those girls who participate in organized sports show more interest in political careers, but fewer girls are encouraged to participate in sports than boys.

While these connections may lack quantitative data, their effect is ubiquitous. Our society emphasizes a woman’s value as it related to her physical appearance; we raise our girls to meet and uphold these standards, preventing them from engaging in other pursuits such as politics or other fields not traditionally associated with femininity.

Interestingly, it has become somewhat fashionable for companies who market to women to attempt to appeal to a broader range of the meaning of beauty. For example, Dove’s Real Beauty campaign, which features models of all shapes, colors and sizes, encourages women to embrace their physical appearance, whatever it may be, as beautiful.

Similarly, current pop music sensation Meghan Trainor proudly boasts of her size, (she “ain’t no size two”) in her billboard topping All About that Bass; she sings that even though the magazines feature extremely thin women, that in reality “boys like a little more booty to hold at night.”

Yet where the Dove campaign misses the mark is that it still ties a woman’s value to her appearance and body. In other words, it’s still about being beautiful, even if the definition has changed. And in All About That Bass, the value of being bigger than a size two is grounded in the fact that it’s what men actually prefer. Neither of these efforts effectively counter persistent norms regarding a woman’s value being tied to her body, and the sexual desires of men (Everydayfeminism.com has a great post about this very idea).

And it is here where Schumer’s effort gets it right. Schumer recognizes the absurdity of a society that values women on the basis of their appearance; instead of reinforcing or even expanding these notions of beauty, she makes viewers question them altogether. This upending of objectification is embodies by her “Milk, Milk, Lemonade” sketch where Schumer, along with Amber Rose, sing and dance about big booties—talking about what one’s anatomy is physiologically designed for, rather than the sexualized desires they arouse in some men. By demolishing archetypal ideas of beauty, Schumer helps young women discover a counter-narrative that, with any luck, might just change the way in which girls see themselves. And given her political family, maybe she could work toward convincing more women to run for office too.

.

Meredith Conroy is an assistant professor at California State University, San Bernardino. She serves as the chair of the Western Political Science Information Technology Committee, and is a member of the Status of Women in the Profession Committee. Her book, Masculinity, Media, and the American Presidency, publishes in October 2015.

Meredith Conroy is an assistant professor at California State University, San Bernardino. She serves as the chair of the Western Political Science Information Technology Committee, and is a member of the Status of Women in the Profession Committee. Her book, Masculinity, Media, and the American Presidency, publishes in October 2015.