Letter to a Future Lover: Marginalia, Errata, Secrets, Inscriptions, and Other Ephemera Found in Libraries, by Ander Monson

Graywolf Press

$22.00

176 pages

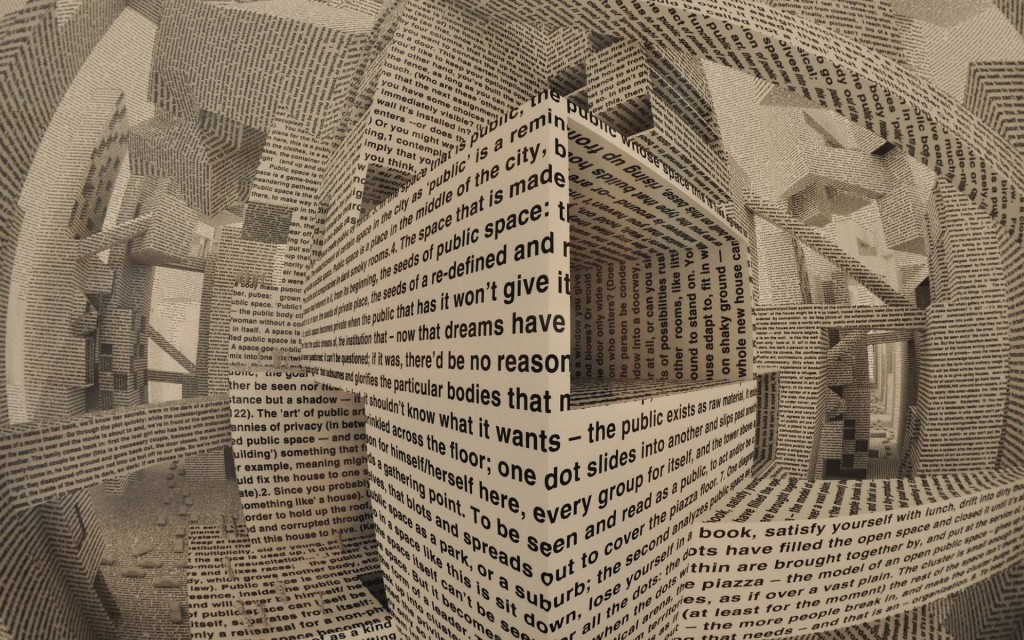

In Letter to a Future Lover, Ander Monson creates a labyrinth in miniature, composed from the human amendments (errata, underlines, tears, hairs) and any bundle of pages he encounters. This includes library books from shelves as far-flung as Biosphere 2, to the tossed manuscripts of a well-loved professor, to a card catalogue repurposed as scrap. These are biblio-rejects—books that smell of loneliness, books that flop open like happy pups at the touch of Monson’s hand.

Letter to a Future Lover tells the story of a man (Monson) who seeks himself in the air between pages, pursuing relationships with spectral teenagers from 60-year-old high school yearbooks, and impassioned hypothetical dialogues with the hateful defacer of a copy of Gay & Lesbian Biography—among other public texts. But the central figure is Monson, stalwart in his pursuit of lacunae. If a central relationship plays out, it is between Monson and himself.

At 176 pages, Monson’s labyrinthine assignment scans as noble and naïve, an attempt to form something whole out of lost parts. What emerges is a lonely story—the author tracing signs of an absent body, each book a measureable distance between Monson and another. The most comic example of this is a Braille edition of Playboy, an item so richly palpable, and yet illegible to Monson. He doesn’t say it, but the subtext of this object is—there really are people who read Playboy for the articles. Not him, though.

Textured language (as Braille literally is) feels analogous to the reading that Monson does, physically navigating the libraries and many thousands of pages that form his projected labyrinth. As Monson explains, the key distinction of a labyrinth (versus a maze) is that the former is unicursal, moving towards a center. But despite the promise of texture and turns, Letter to a Future Lover arrives at a disappointingly flat destination—endpapers.

Throughout, Monson’s selections fascinate with his curiosity for the cryptic and small, and although at times he addresses a “dear” reader, that dearness is ironic, referential, a bookworm’s tic. The experience is less of a “dear reader,” and more of a proxy, as Monson trawls the interiors of these books for signs he can deep-read. “To read another writer’s marked-up copy of a book is to read two books at once, text and paratext, the passage and the pilgrim’s process, to see how an animal takes root and begins to worm inside a brain, even if we don’t get to see its final bloom.” Here, Monson is his own paratext—reflexively citing other books he’s read, other writers he’s known, with quickness and wit. At times, Letter can feel like an ambling literary puzzle.

Late in Letter (although “late” is misleading in the whorl of a labyrinth), Monson invokes the image of a chain of paper dolls—a man in finite recursion, strung between two hands. “Finally, that is what we love: human taint, human constraint. Not infinity but the best a man can grasp,” he writes, earlier, although the sentiment haunts every page. Letter itself often reads like an exercise in curated solitude—an alphabet’s worth of short essays—running from A-Z—each one presenting the same man, every two pages or so, bound between his own two hands. It is alternately pleasant and oppressive, as each letter brings forth a new document to study.

Monson’s previous book, the NBCC Award-nominated Vanishing Point, shares Letter to a Future Lover’s inward curl. But Letter has a stifling quality, an effect of Monson’s hyperbolic bookishness. He is at home in the guts of a university library, addressing someone like him. Monson is a devoted lover, in the way that a lover talks about the object of affection with a microscopic vigor that can be difficult to feel acutely second-hand. Best is when he draws out the strange, somewhat gross intimacy of library books. From two mysterious hairs discovered in the spine of French philosopher Deleuze’s The Fold, (which happens to discuss the folded nature of a labyrinth), Monson imagines the human shape that once sat where he sits. In moments like these, the book is less a receptacle for marginalia than it is a mirror, used to reflect the past and the future (the future lover). This is when Monson’s conceit works, spurring tenderness for the books you too have read, and shed upon.

Letter to a Future Lover offers a warming premise, if sometimes through tedious execution, adding up to a project done in the spirit of curiosity that fails to solidify. Monson combs the borders and margins of obscure/forgotten/damaged texts found in obscure/forgotten/damaged libraries as a way of getting closer to the book object, but the findings feel sparse, even if tangibly they aren’t. “A library is a synonym for slow,” writes Monson, one of his many lyrical, matter-of-fact statements. It is also a synonym for growing aloneness as each entry proves—Monson uninterrupted by other voices within his deepening labyrinth.

Although lonely, Letter provides a true sense of being ensconced—which, depending on your disposition, might seem either a comfort or cage. “When we say book do we just mean container?” asks Monson, a question that subtly dogs him at every turn, the borders of books proving both less and more membranous than can be articulated. But Monson tries to inhabit the space contained, shoulder-to-shoulder with us, his phantom reader.

•

Naomi Skwarna is a writer and theatre maker living in Toronto.

Naomi Skwarna is a writer and theatre maker living in Toronto.