In the conclusion of her 1976 essay “Memoirs of a Non-Prom Queen,” Ellen Willis describes her own high school psychology as “a version of the Laingian fallacy—[thinking] that because a destructive society drives people crazy, there is something dishonorable about managing to stay sane.” This vehement disavowal of her time as a “teenage reject” (her words) is just one example of why Willis’s work so often seems like it might have been written yesterday: she is as willing to analyze and deconstruct her own opinions and biases as she is the topics that she so incisively critiques.

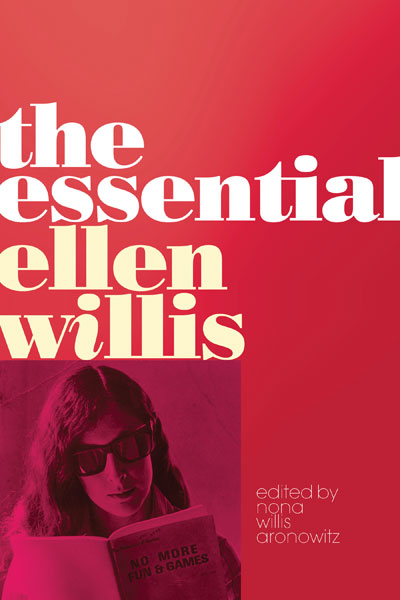

The result is intimate—Willis’s writing connects the personal and the universal across genres, from her pieces as The New Yorker’s first pop critic in the ’60s and ’70s to her pieces on radical feminism, war, and politics (and how they all fit together). Now, the entire range is available in the new volume The Essential Ellen Willis, a 500+ page collection that spans her 40 year career (and thus, 40 years of American cultural history). To celebrate its release, the anthology’s editor (and Willis’s daughter) Nona Willis Aronowitz, along with the NYU Cultural Reporting and Criticism program that Willis founded, hosted a party last Friday at DUBMO’s Galapagos Art Space, complete with readings by a number of prominent writers, critics, and Willis fans.

Each chose a piece they admired—pieces that also often ended up reflecting the writer’s own intellectual inclinations; as NPR’s Ann Powers wrote, “I’m starting to think Willis might have invented the way my generation thinks about pop.” Nona, a journalist whose writing on liberal politics and feminism picks up where her mother left off, kicked off the festivities by reading “The Last Unmarried Person in America,” a biting satire of Regan-era conservatism. Cord Jefferson, a leading voice on race and identity politics, read “Memoirs,” the first piece mentioned—Willis’s introspective dissection of her own identity, past and present. Irin Carmon read “Abortion: Is A Woman A Person?”, with the cheers of every woman in the room serving as testament to the essay’s continued (if unfortunate) relevance.

Each chose a piece they admired—pieces that also often ended up reflecting the writer’s own intellectual inclinations; as NPR’s Ann Powers wrote, “I’m starting to think Willis might have invented the way my generation thinks about pop.” Nona, a journalist whose writing on liberal politics and feminism picks up where her mother left off, kicked off the festivities by reading “The Last Unmarried Person in America,” a biting satire of Regan-era conservatism. Cord Jefferson, a leading voice on race and identity politics, read “Memoirs,” the first piece mentioned—Willis’s introspective dissection of her own identity, past and present. Irin Carmon read “Abortion: Is A Woman A Person?”, with the cheers of every woman in the room serving as testament to the essay’s continued (if unfortunate) relevance.

Willis’s music criticism also remains shockingly modern: Ann Friedman, who cited the writer in her piece on the moral ambiguity of “Blurred Lines,” read “Beginning To See The Light,” an essay in which Willis explains how she can appreciate sexist music without appreciating sexism (as Nona says on Tumblr, a necessary prerequisite for any Yeezus listener). “Wow, I can’t believe all the groups here, and I’m not even listening to them,” Rembert Browne (no stranger to the music festival himself) read in a quote from “The Cultural Revolution Saved from Drowning,” Willis’s piece on Woodstock—pretty much the single most accurate description of a music festival ever written.

Though many of the topics were serious, the mood was light—a criminally underrated female writer, finally getting her due both in print, and in a barrage of essays that show her vital importance to this generation of writers and critics. Her “courage to face the awful truth” is an inspiration to the writers everywhere, who are all (myself included) just trying to figure out “the point of sitting home scratching symbols on paper, adding [their] babblings to a world already overloaded with information.”