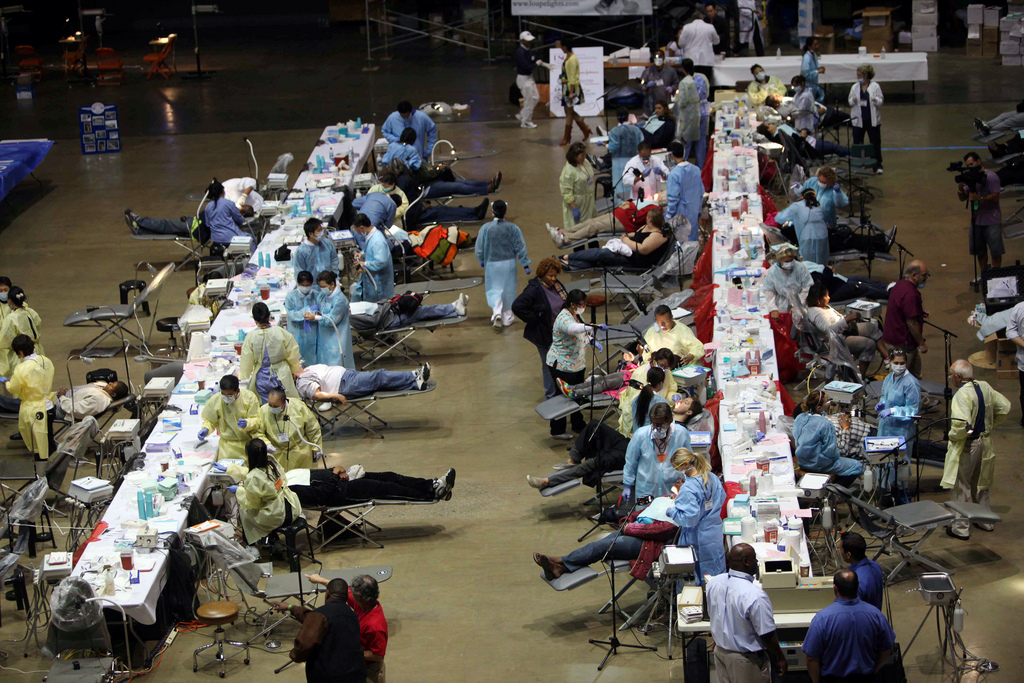

People receive free dental care during a free medical care clinic sponsored by the nonprofit group Remote Area Medical, in Inglewood, Calif., Tuesday, Aug. 11, 2009. (AP Photo/Nick Ut)

On the first day of the shoot, we met Val Crosby. At the time, Val was living in a trailer without running water in Butler, TN with her husband Jonathan and working at the Iron Mountain Inn doing housekeeping and odd jobs. Val, a beautiful woman in her forties with clear blue eyes, initially didn’t want to be interviewed for the film because of a degenerative nerve disorder that’s left her with a mouth full of visibly broken and decaying teeth. Her dental problems have made it difficult for her to find regular work because, in that part of the country, bad teeth are often associated with meth addiction. Jonathan told us that he hasn’t been able to kiss Val for over a year due to her near-constant pain. The pair were planning to head to the RAM clinic set up in the Bristol Motor Speedway that weekend in the hopes of getting all of Val’s broken teeth pulled and replaced with new a pair of dentures. She decided to be interviewed because she hoped that having her story recorded might end up helping others.

By their very nature, Remote Area Medical clinics can only do so much. There was a shortage of dentists the day Val attended, so, even though she arrived in the parking lot nearly twelve hours before the gates opened at 6AM in order to secure a good spot, there just weren’t enough resources to get what she needed done. When Val left the RAM clinic that weekend in April, she left with her teeth still broken but her pain intact— exhausted, thankful for the care she did receive, but disappointed.

When we premiered Remote Area Medical at the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival in 2013, ABC News ran a story about the movie and focused in on Val’s plight. The headline, “Too Poor for Dental Care Robs Wife of Husband’s Kiss,” sat atop the ABC News website for over a day, with Val’s picture prominently displayed. Val’s story was now reaching others—many of them. A few days later, we received word via e-mail that an anonymous donor had read the piece, reached out to Val and offered to pay for her dental care. Soon, she had a set of new dentures. We doubt she sat before our cameras that day in April a year before with any idea that sharing her story would change her circumstances so dramatically. We never imagined that it’d be so soon after introducing the film to audiences that we’d start seeing positive results. “Changing the world” is the stated goal of so many documentary films and filmmakers, but it’s rare that the effects of a film are so immediate.

Creating and defining the “impact” of documentary films is a fixation of the contemporary nonfiction filmmaking community, from filmmakers to financiers to the new class of engagement consultants bent on creating this very thing. Impact is often discussed in terms of achieving legislative and policy goals, or altering consumer behavior enough to shame corporate entities into abandoning unsavory practices. There have been many notable successes: An Inconvenient Truth, Super Size Me, The Invisible War, and Blackfish. But these days, for every film that does move the needle, there are now dozens more flooding the marketplace that have little lasting effect at all.

What impact the impact obsession has had on the art of nonfiction filmmaking is a question worth asking. A documentary filmmaker can be an activist, but this does not mean that they must be, and there’s a rich history of creative nonfiction filmmaking that makes pushing formal and aesthetic boundaries an end in itself. Advocacy and art don’t necessarily cancel each other out, but there are ways in which the demands of the former can, if left unchecked, iron over the intriguing nuance that can enrich and enliven the latter. The focus on what a film could achieve in the real world over what it has achieved as a sensory and emotional experience, what it can do as opposed to what it is, has been reproduced in criticism of documentary films so thoroughly that films that aren’t striving at all to get petitions signed or legislation passed are now judged under this rubric. This narrowness is detrimental to documentary as a whole. It flattens a rich and multivalent form of art making; for many critics, narrative films can be dramas, comedies, action films, science fiction, romances, commercial, independent, whereas documentaries are just…documentaries.

The ability of documentary film to step in where journalism was beginning to fail due to financial constraints and the shift towards more succinct, up-to-the-minute coverage feels intuitively important. As more thoroughly researched and written long-form pieces dwindled over the past decade, audiences and critics alike began to realize that they could turn to documentaries to provide something that the news often no longer did. This cratering of journalism coincided with rapid advances in technology that took documentary from an expensive, celluloid-based medium into a new, cheaper digital realm. Now, anyone can make a documentary, and sometimes it seems like almost everyone has tried. Given that most people have opinions—often passionate ones—about a whole range of things, documentary soon became the medium of choice to pick all sorts of bones and deliver the argument, whether in favor of a vegetarian lifestyle or against the U.S. occupation of Iraq. Suddenly, docs could be big commercial winners at the box office and there were plenty of them to go around.

Over the past decade, there’s been a subtle but crucial shift in focus from expecting that documentaries fill a lack in journalism to asking that documentaries be weapons of advocacy. Alex Gibney’s Academy-Award nominated Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room from 2005 worked merely to journalistically unpack the Enron scandal for viewers confused by what had actually happened. It was a cautionary tale, for sure, but advocated nothing specific. By the time of Charles Ferguson’s similarly, rigorously researched and reported No End in Sight (executive-produced by Gibney and also nominated for an Academy Award) in 2007, the endpoint of the cinematic journalism on offer was policy change. The potential explanations for this shift are myriad and politicized. Was it the box office performance (if not political success) of Fahrenheit 911? Was An Inconvenient Truth in 2006 a defining catalyst? To what extent did liberal exhaustion with the seemingly never-ending morass of the Bush administration play a role? (To be sure, when we talk about documentary, we are most often talking about films that ratify liberal prejudices.) Tracking this shift is worthy of a book-length study, but we now live in a world where a film like our Remote Area Medical, and many similarly observational documentaries, are asked to do things they’re not even setting out to accomplish. Forget your formal ideas, documentary filmmakers, content is king.

Sometimes a film like Laura Poitras’s CITIZENFOUR comes along that satisfies across the spectrum. It’s a film that could only exist using the tools of cinema, but it’s also one whose political intentions are unmistakable, even if viewers aren’t provoked to hit up a website at its close. Compare that to Charles Ferguson’s slickly-produced Inside Job, an attempt to distill the complexities of the financial crash. There’s nothing remotely cinematic about that film’s blend of talking heads interviews and graphics—it might as well have been a magazine piece, and actually had been in many publications in the years prior to the film’s release. Yet the fact that both of these films have won the most prominent award given to documentary films (the Oscar) speaks to the confusion around the purpose of the form, and how we evaluate it. What are documentaries supposed to do? How about one thing at least: be good movies.

Our latest film, This Time Next Year, chronicles a New Jersey barrier island community, Long Beach Island, in the year after hurricane Sandy. The film hunkers down with a cast of small business owners, school teachers and teenagers as they slowly and painfully pull their disrupted lives back together. An audience member at a recent Washington, D.C. screening asked why we weren’t more pointed in our probing of subjects like evacuating LBI forever, while another said it “would have been more courageous” to call out conservative politicians and deniers of climate change. Frankly, we made the film we did because we were more interested in exploring the psychological impact of living through a natural disaster on a large scale and questions regarding the fragile nature of home and security. When we screened the film on Long Beach Island about a year after Sandy made landfall, an audience member raised his hand and thanked us for making a film that allowed the community, still struggling to get back to normal, to see just how far they’d come.

Although we feel strongly about the issues addressed in our films, we hope that the act of seeing with one’s own eyes, rather than being told through a carefully arranged thesis statement, will inspire compassionate thought and action. Sometimes it is the very fact that a film isn’t overtly telling you what to believe, what to do, that creates a deeper shift in ideology, that difference between feeling overwhelmed by information and intention, versus the much more powerful experience of coming to more concrete conclusions on your own. Perhaps this is naive thinking. Perhaps the world needs documentary to rise up against injustice. Impact can come in many sizes and shapes, and just because a documentary isn’t addressing pressing needs in the most obvious of ways doesn’t mean it lacks value. Remote Area Medical hasn’t changed the face of healthcare in America, but many people around the U.S. have met Val, heard her story and maybe learned a little bit about a pocket of Appalachia that often goes ignored. Even better, Val got a new set of teeth because we went to Bristol to make a movie. That’s change we can get behind.

•

Farihah Zaman is a Brooklyn-based filmmaker, critic, and programmer. She currently writes for Reverse Shot, Huffington Post, Filmmaker Magazine, and AV Club, among others.

Farihah Zaman is a Brooklyn-based filmmaker, critic, and programmer. She currently writes for Reverse Shot, Huffington Post, Filmmaker Magazine, and AV Club, among others.

•

Jeff Reichert is the co-editor of the online journal Reverse Shot. He and Farihah Zaman produced and directed the award-winning films Remote Area Medical and This Time Next Year.

Jeff Reichert is the co-editor of the online journal Reverse Shot. He and Farihah Zaman produced and directed the award-winning films Remote Area Medical and This Time Next Year.