Can you ever really know a place?

Rebecca Solnit and TBQ’s Anisse Gross, both San Francisco–based writers, sat down recently to deliberate that perennial question.

Photo: redbeansandrice / Flickr

Having edited two atlases of American cities, with a third on the way, Solnit has long been grappling with issues concerning the future of mapping and construction of place.

Her atlases—the first of which focused on San Francisco, the second on New Orleans, and the third will focus on New York City—depart from any traditional conception of mapmaking and instead feature the work of various writers, cartographers, artists and historians. In these works, a panoply of infinite voices provides a cross-section through space and time, opening windows so that readers have new views of a city they may have thought they knew inside and out.

An extremely prolific writer, activist, historian and chronicler of culture, Solnit has written sixteen books, and is coming out with two essay collections this year, Men Explain Things to Me and The Encyclopedia of Trouble and Spaciousness. Throughout Solnit’s body of work, the thread of place constantly and continually extends.

TBQ: We both live in San Francisco, a place I think we both love deeply. What about the format of an atlas attracted you when compiling a book about San Francisco?

RS: I decided to be a writer when I was six. I will always be a writer first, but there are certain things you can say with maps that you can’t say any other way. If I say that 99 people were killed in San Francisco in a year not long ago, that’s a nothing factoid, but if I show you where each of those violent deaths took place, so that you can see that you might cross paths with a tragedy, that death has a geography, that far more people die on the poor asphalted east side than the more bucolic west side, it impacts you differently. Geographical and spatial relations come alive with maps.

An atlas also let me do a bunch of things I wanted to do. One was to provide a counter to the rush to online mapping with its hideous aesthetics, evanescent images, normalizing tendencies to show all places merely in terms of practical needs, and consumerism. There are all these restaurants and shops on Google Maps, without any indication of, say, where great women lived or endangered butterfly species live.

*******

Thus we mapped shipyard building [with] African American cultural contributions in the Bay Area, which are tied by the way: those shipyard jobs drew black migrants during the Second World War and changed the complexion of the region to this day. I wanted to make maps beautiful again and to demonstrate that they are always art as well as science. And I wanted to come home after spending the Bush years on nationally and internationally focused projects. I more than came home; exploring the place on foot and in archives and books, and working with people with varied, deep, and wonderful relations to aspects of the area, I came to a stronger knowledge of it than I had before.

What do you think is behind the enduring fascination with maps?

Until I produced an atlas, I didn’t realize that a lot of people love maps, and that love is a joyous, ebullient passion unlike any other. I still don’t know, but I have notions. I think that maps are puzzles that appeal to our puzzle-solving minds, elegant puzzles about what a place is and where on Earth we are. I think that sometimes they’re beautiful (and it’s the beautiful and interesting ones we love; a printed-out computer map with the hideous blue upside-down teardrop shapes is not moving a lot of hearts or alighting a lot of minds).

The beauty of maps is a hybrid of cartography and language—and sometimes representational art. I think that in some deep way we’re all lost and maps promise to let us find ourselves—in 1920s Shanghai, or a misshapen North America from the 17th century with a vague West Coast, or a snappy gas station map of Arizona from 1966. To find ourselves even in places we’re not, because reading a map is a business of orienting, of interpreting data about actual place.

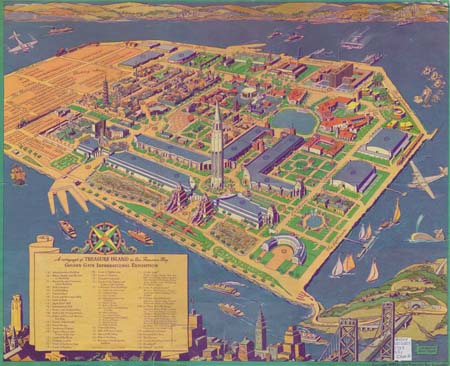

Map of the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco, 1939 / UC Berkeley Bancroft Library

Maybe the fact that actual places are a little optional now—you can live indoors or go from airport to chain hotel to chain-store mall and hardly know if you’re in Copenhagen or Tokyo—has sharpened a passion for the specifics of place. Too, a map of an actual place has something not even a photograph has: the promise that you can enter that space that is depicted, a special kind of relationship between reality and representation. But these are merely theses. The joy is a little mysterious, a terra incognita of the psyche.

San Francisco is going through a very difficult time. Especially when it comes to cities, you often hear it said that change is inevitable. Do you think that’s a useful adage for characterizing everything that takes place in the lifetime of a city?

I listened to some murderers in San Quentin use the passive tense to step away from culpability for their crimes a couple of years ago. And when I hear those kinds of constructions in discussing evictions, gentrification, the triumph of the rich over the poor, I see similar cover-ups made out of syntax and evasion. It’s a way of denying that specific people, groups, forces, and systems actively create change to advantage some and disadvantage—or destroy—others. It’s not inevitable that a speculator might buy the home of a 97-year-old woman who’s lived there for more than four decades and begin eviction proceedings against her soon thereafter.

*******

Reading the essay on all of San Francisco’s long-gone cinemas made me reluctantly nostalgic for a time period that I never even lived through. Is nostalgia for a bygone era necessarily a bad thing?

Photo: kodama / Flickr

I don’t know if it’s good or bad. I think it’s important both to find things to love and document in the present, and to know how the present came out of the past and what that past looked like. I drove past old movie theaters in the East Bay and was thinking again about how beautiful it was that people used to enter these temples of darkness and dreams to commune together around the stories flickering on the screen. I think nostalgia is dangerous when you think the past was altogether better than the present: I love the way people used to coexist in the semipublic space of the theaters, the total immersion of film on the big screen, and the little rituals of going to the movies; I know that in other respects the heyday—say the teens to 1940s—of cinema was one in which straight white Christian men had a headlock on privilege and power in the country.

Adrian Camarena contributed a lovely oral history of the gang members and migrant workers of the Mission. She writes that she hopes readers “might be emboldened by the thought that you know them better, but you do not. For you must travel that distance on your own,” as if to suggest that maps are merely entry-points for the curious. What do you think?

I think she was talking more about her essay profiling some Latino residents in the Mission district than the map the essay accompanies. She’s saying that yes, you’ve met these people she connected deeply with and wrote about beautifully, but don’t confuse this with making you an insider or even informed. You have to form those relationships yourself. And maybe that all of us are a little mysterious: Here are some things you can learn about these people, but grant them the complexity that goes beyond what you read in a sketch.

You write in “Right Wing of the Dove” that the Bay Area is home to many right-wing organizations and institutions that function as a part of the military machine. To some degree, every city suffers under its own clichéd identity. Can atlases play any role in dismantling them?

There are many kinds of atlases, and the traditional kind contains either maps covering different places—the fifty U.S. states, for example—or the same place in different ways—those atlases showing one state or region’s crop yield and duration of residence, for example.

My atlases are cultural, aimed at deepening what is known and dismantling what is assumed. For example, people think that the Bay Area is all about peace, love, and left-wing values, so “Right Wing of the Dove” demonstrates that the Bay Area is a crucial place for military and conservative activity.

Soviet Map of San Francisco, 1980, Prelinger Library / Laughing Squid

Mobile maps and the Internet in general are becoming increasingly customized to users’ preferences; what we search for and look at and click on determines what we see in the future. Should we be concerned? How in the near future will we get exposed to things we don’t even know we might be interested in?

Programmer/writer Ellen Ullman wrote a brilliant essay way back in May of 2000 called “The Museum of Me.” It critiques the upbeat rhetoric around museum websites that promised you could curate an online museum of only what you wanted to look at, and other ways the Internet allows people to withdraw from a shared reality into [either] a customized one or one only shared with like-minded people. She saw real danger in this early on.

Fourteen years later we’re in that world where you can go to websites to reinforce your conspiracy theories or anti-vaccination and climate-denial delusions or racism or you name it. The Internet is a giant centrifuge in which society spun apart into its constituent ingredients, and some of the rift in American culture comes from the way people at the poles of opinion get their reinforcement from their chosen media. The right seems to have left fact-, research-, and science-based reality altogether, but the left gets some pretty loopy stuff, too. We need windows, not mirrors.

Maps are literally documents of our common ground: We can all go walk down Fifth Avenue or the Las Vegas Strip or the Appalachian Trail, but even online maps, which thanks to the monopoly power of Google are mostly Google Maps, tend to reinforce a middle-class consumer reality. People can put data on the common maps, but they tend to mostly put restaurants and shopping stuff there, not history or ecology. This tells us a neighborhood is where you pay for services and eat stuff, not where this person died and these tenants organized and those birds migrate through and that ancient tree still stands.

*******

It was so satisfying to make a map of the Mission District in 2009 with life stories, gang territories, churches, soccer fields, remittance shops—to indicate where immigrants move money back to their homelands, a map that shut the fuck up about food and shopping. Maps can be mirrors of the expected and familiar, or the opposite.

Jane Jacobs, in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, writes, “By its nature, the metropolis provides what otherwise could be given only by traveling; namely, the strange.” It seems to me that these “cultural values” of likeness and preference that are being promoted are a direct threat to the true nature of a city, which is the strange, different, cultural other.

What a beautiful line! Many years ago I wrote that to know something is for it to become familiar, to know it more deeply is for it to become strange again. Then I wrote a book called A Field Guide to Getting Lost. The great lovers and walkers of cities pay close enough attention and move daringly enough through the city that they encounter difference, mystery, the unexpected, the tender and desperate little moments of strangers passing by, come to know the rhythms and rites of the city and some of its secrets, and know, too, that there are more secrets than anyone can ever know.

*******

One of the things I love about New York City is that everyone walks, everyone takes the subway, so that rich and poor, white and nonwhite, native and immigrant coexist. Fear of the other is not so strong when you actually coexist with that other daily, and it’s key to a democracy, I believe. In a democracy we believe we can make decisions together and our well-being is also a shared reality; we are not separate. Gated communities, private security, private schools are withdrawals from the shared space and shared experience, and they have their informational and online corollaries. People seem to feel more and more unequipped to deal with the unknown, with uncertainty, with terra incognita. But adventure among the unknown gives us our lives or enlarges and enriches them.

I remember that during the dot-com boom the rhetoric was particularly strong about how awesome it would be to never leave home and never encounter strangers, that these were dangerous, time-wasting things. That rhetoric hasn’t gone away; it’s just quieted down, as so many people settle for Amazon for their bookstore and eBay for their flea market and get so busy staring at their phones they don’t look around them much. We’re in a hyperutilitarian age that is telling us that all that exists can be bought and sold and the rest doesn’t matter—maybe that’s why a techie in Southern California is marketing a nutrient sludge along with the assertion that eating is a waste of time, why the arts and humanities are being devalued because they’re not profit-maximizing rackets.

*******

Which I think a lot of lives are now; a big part of my writing has been to try to describe and value those things that are not quantifiable, commodifiable, controllable: epiphanies, awareness, those beautiful moments when people come together as civil society, whether to pick up after a disaster or overthrow a disastrous regime, beauty itself, and the pleasures that don’t get named much.

Google recently bought satellite-imaging company Skybox, allowing Google Maps to shift into real-time, live, high-resolution mapping, and to trade in what’s known as “manhole and mailbox” imagery. The U.S. Department of Commerce lifted the ban on satellite imagery lower than 50 cm. What do you see these developments reflecting, both in terms of privacy and their impact on our ideas of place?

I think we’re moving into a war, and the soldier who went on ahead to sacrifice himself for our liberties is Edward Snowden. We are in an era where private has three terrifying aspects: the privatization of neoliberalism, the withdrawal from the shared public sphere of values and participation I spoke of; the withdrawal into unaccountable secrecy of the most powerful forces around us, both corporate and government—and corporations control more and more of our lives as most of us become more and more dependent on the technology they control; and loss of privacy for ordinary people whose searches, whose phone calls, messages, and networks of association are all being tracked, most especially by Google and the NSA.

Privacy is a power, a protection; now they have more of it and we have less, making them less accountable and us less free. Glenn Greenwald just gave a talk in San Francisco, where he commented that the big tech firms didn’t really give a damn about our privacy until their violation of it in cooperation with the NSA and for their own purposes became a business issue. Europeans in particular don’t want to use services that are not private, and that’s bad for their business.

There’s another issue that Google in particular now controls so many kinds of information that it’s hard to operate online without getting mixed up with them: they have the maps, the email, the search engine, the video channel, the file-sharing, the storage, and many, many other services that rope people into their information-gathering network. Because 95 percent of their revenue is from advertising, and advertisers give them money because they have all this data on us that allows us to be targeted for ads. What else will that data be used for? Nothing they’ve done convinces me that they are a trustworthy guardian of our information, and the increase in mapping data is just part of the enmeshment in the machinations of an unaccountable and virtually unregulated global superpower. Information is power, and that’s as true of map information as your personal data: a corporation that compounds both kinds is pretty scary.

Photo: guylombardo / Flickr

I sometimes think that San Francisco is becoming irreparably “Manhattanized”—turning into a bland, private enclave for the rich. When is a city no longer truly a city? And what makes a place a city, apart from density?

I went to see the amazing Circus Automatic the other day, a show of contortionists, acrobats, and aerialists doing breathtakingly beautiful things. They’re part of the circus-arts scene that thrived in San Francisco the last couple of decades. Now it’s being pushed out, because a supremely strong, skilled, and flexible woman who can stand on her hands while shooting a bow and arrow with her toes is not as well paid as a software engineer.

*******

If you read Joseph Mitchell’s midcentury account of a Manhattan with a thriving fish market, ancient taverns, bearded ladies, theaters for the poor, and complex economic and social layers, you see that kind of diversity: Manhattan before it was “Manhattanized.” Like Balzac’s Paris or so many other visions of the teeming city, it’s the metropolis as the meeting place of all peoples. A great city is like a thriving ecosystem with many organisms in it, though it’s worth pointing out that the whole United States and Manhattan south of Harlem were a lot whiter than they are now.

But wealth suburbanizes cities; it pushes out the economic and employment diversity, and often ethnic diversity, and it also shuts down room for experimentation and for art and culture. On San Francisco’s Fillmore Street, the 1960s radical artists’ space the Batman Gallery turned into a classical music store by the 1980s; in the 1990s it turned into a Starbucks; so as the neighborhood gentrified the site went from cutting-edge cultural production to historic cultural presentation to chain store for consumables. Wealth is not as good for culture as people tend to believe. Bookstores—including the oldest black-owned bookstore in the United States, also on Fillmore Street—are being pushed out for chain stores and restaurants in San Francisco, and I know Manhattan bookstores have also been struggling.

Photo: felixdv / Flickr

My city is right now losing schoolteachers and other people in the middle-income bracket; its African American population has been in free-fall for a long time; and I look at busboys and store clerks and wonder how on Earth they get by or how far away their homes are. I know that in Manhattan most people doing the vital things—firefighters, street-cleaners—don’t live there because they can’t afford to. So in a sense the work is outsourced, just as manufacturing is when the things we use are made in sweatshops in Bangladesh. Cities always draw from the realms around them for food, for example, but the mix is what made it rich; that mix is being simplified, strained, eliminated in the most affluent places. There’s so much more that could be said, about corporate globalization, financialization, growing economic inequality, the reversal of white flight, the rise of chain stores…

Speaking of Manhattanizing, your next atlas is on New York City, which residents sometimes just call “The City.” Why is it so often regarded as the ultimate American city?

New York, with its big brash ambitious melting-pot mosh-pit and its proximity to Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty, is very American, and even emblematically American, I suppose.

*******

One of the most beautiful things I’ve seen (at a distance) in New York City was the way that tens or hundreds of thousands evacuated on foot the morning of 9/11, confident in their own ability to navigate distances without mechanical intervention, in the people around them, in the city itself. I wonder whether people would’ve even understood that you can walk your journey of many miles in, say, Atlanta or Los Angeles.

Of course there are many New Yorks—from the homeless person’s city to the limousine passenger’s city, from outer Queens to the Upper West Side. It’s dangerous to generalize. New York is both Wall Street and Occupy Wall Street, speaking of civil society and those who are willing to live in public, and are each of those phenomena American or anti-American. Both New York and the U.S.A., to paraphrase one of the city’s greatest sons, contain multitudes of versions and visions.

•

Photo: Adrian Mendoza

Writer, historian, and activist Rebecca Solnit is the author of sixteen books about environment, landscape, community, art, politics, hope, and memory, including two atlases, of San Francisco in 2010 and New Orleans in 2013; this year’s Men Explain Things to Me; last year’s The Faraway Nearby; A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster; A Field Guide to Getting Lost; Wanderlust: A History of Walking; and River of Shadows, Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West (for which she received a Guggenheim, the National Book Critics Circle Award in criticism, and the Lannan Literary Award). A product of the California public education system from kindergarten to graduate school, she is a contributing editor to Harper’s and frequent contributor to the political site Tomdispatch.com.

Anisse Gross is a writer living in San Francisco.

Anisse Gross is a writer living in San Francisco.

13 thoughts on “Documents of Our Common Ground”