“Relingos: The Cartography of Empty Spaces” is an excerpt from Sidewalks, a collection of essays by Mexican novelist Valeria Luiselli. It was translated by Christina MacSweeney and published by Coffee House Press in 2014.

Work Suspended

On the Paseo de la Reforma, that grand avenue simulating the entrance to an imperial Mexico City that of course no longer exists, there’s a quadrangle of tiny absences, small plazas, where once there were things that are now only gaps. As if the perfect, majestic smile of Madame de la Reforma now lacked a number of teeth. Only God and perhaps Salvador Novo—modernist chronicler of the city—know what was there before the appearance of those empty spaces.These urban absences, as they might be called, were formed during the extension of the Paseo de la Reforma in the 1960s. The widening of the avenue and the addition of a new stretch were accompanied by the indiscriminate demolition of the buildings in the area. As this new road cut diagonally across the orthogonal layout of the city, some rectangular plots became triangular or trapezoidal. And, since the construction of buildings in these irregular spaces—leftovers from the Paseo—was inconceivable, the asphalt and paving-stone trapezoids and triangles remained like odd pieces of a jigsaw, the origin and purpose of which no one remembers any longer, but which, equally, no one dares to either destroy or use in any permanent way. Nowadays these residual spaces on and around certain corners of Reforma—between the enormous new junctions with the avenues Eje 1 Norte and Hidalgo—are abandoned to the perpetual comings and goings of ambulant street vendors, tourists, delivery men, petty thieves, the homeless, people taking strolls, dust, and debris.

A group of architects from the National University (UNAM), headed by Carlos González Lobo, have christened these spaces “relingos.” I’m not sure where the term comes from, but I imagine it could be related to the realengas of old Castilian, a term that refers to pieces of land not belonging to the Crown, abandoned to disuse. (The strange ups and downs of words: in certain Latin American countries, realenga is now used to talk about an animal with no owner; in others, the word is synonymous with “layabout.”)

I’m also pretty certain that relingo is derived from another similar concept: the terraines vagues of the Catalan architect Ignasi de Solà-Morales. Just like a relingo, the terraine vague is an ambiguous space, a piece of waste ground without defined borders or limiting fences, a species of plot on the margins of metropolitan life, even if it is physically to be found in the very center of a city, at the junction of two main avenues, or under a newly built bridge.

Coming out from Hidalgo metro station at the exit nearest to San Judas Tadeo church, there’s a small triangular plaza, in the middle of which stands a tribute to the work of Mexican journalists: a statue of the nineteenth-century newspaper editor and politician Francisco Zarco surrounded by a large fountain that bubbles and spits out mouthfuls of gray water. The homeless people of the neighborhood go there with their bars of soap and towels to wash their faces and bodies beneath the bronze figure. At certain hours in the afternoon, that same plaza becomes a six-a-side football field, and at midday on Sundays it’s transformed again, into the venue for a tertulia for the deaf mutes coming out from the sign language mass at San Judas.

An architect friend of mine, José Amozurrutia, once showed me the plans of a possible building he designed for that relingo. What he envisioned there was a theater that would house the hypothetical San Hipólito Deaf League, and provide a space where the congregation of the sign language mass could indefinitely prolong their Sunday gatherings, silently reading scripts and rehearsing plays. I can’t think of a more brilliantly crazy idea for a relingo than a silent theater that has absolutely no possibility of ever becoming a reality.

Crane in Use

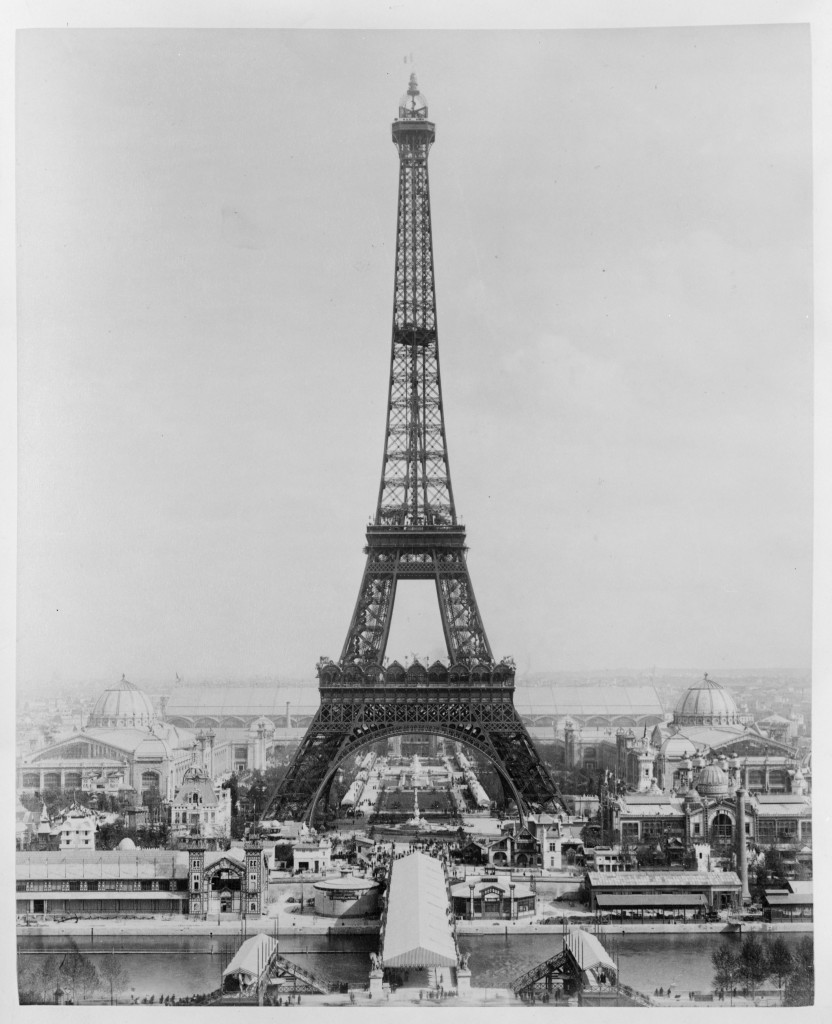

Architecture, according to Roland Barthes, should be simultaneously the projection of an impossibility and the putting into practice of a functional order. In his well-known essay on the Eiffel Tower, Barthes recounts that in 1881, not long before the construction of the gigantic antenna, another French architect, Jules Bourdais, had imagined a “sun tower” for the Champ de Mars—at that time a relingo, a sort of playground or tabula rasa for speculative architects. However Bourdais may have conceived his tower, in Barthes’s version—at least in the English-language translation—the structure was to have an enormous “bonfire” that would illuminate the whole city by means of a complex system of mirrors. On the top floor of the tower, crowning the great beacon decorated with wrought iron galleries, there would be a space to which Parisian invalids could ascend for air therapy.

Although Barthes’s description of the sun tower lacks certain important details—for example, one wonders if the mirrors to reflect the light of the giant beacon would be installed around the city or on the tower itself, or how the invalids would get up to the top of the structure and, once there, not scorch themselves—the idea itself is perfect in the Barthesian-architectonic sense: a semifunctional folly. Whatever the case, being incapable myself of imagining things in three dimensions, I fnd it fascinating to think that a person would stop in the middle of an empty space and conceive there the details of a building full of deaf mutes acting out Macbeth or a tower on whose pinnacle the invalids of Paris would warm their hands on a giant bonfire.

Spaces survive the passage of time in the same way a person survives his death: in the close alliance between the memory and the imagination that others forge around it. They exist as long as we keep thinking of them, imagining in them; as long as we remember them, remember ourselves there, and, above all, as long as we remember what we imagined in them. A relingo—an emptiness, an absence—is a sort of depository for possibilities, a place that can be seized by the imagination and inhabited by our phantom-follies. Cities need those vacant lots, those silent gaps where the mind can wander freely.

No Soliciting

I don’t think relingos are necessarily limited to exterior spaces. A few steps from the plaza where the Deaf League rehearses plays in the imagination of a certain architect is the old Miguel Cervantes Library. The building is an empty interior these days, used and reused for different purposes. Two guards stand at the front entrance: one tall and angular with a melancholy expression; the other short, with a pronounced paunch—like unwitting ghosts of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza.

When anyone enters an official-looking building in Mexico, they’re greeted with variations on the questions: “On whose behalf have you come?” “Who asked you to come here?” “Who do you want to see?” To declare that you haven’t come on anyone’s behalf, that no one recommended your visit, that you don’t need to consult any person in particular, that you’re taking a walk, and would like to go inside to take a look at the ceiling—just for the sake of it—seems to disconcert the angels in blue who guard the entrances to these bureaucratic paradises.

One day, after a certain amount of obstinacy on my part, the two guards of the ex-Cervantes library finally allowed me to pass into the ruined interior. Inside, there was not the slightest trace of the volumes that had once resided there—perhaps just a screw clinging to the peeling wall, against which a bookcase had rested. But there was still an air of bookishness: a heavy atmosphere, the stink of squandered ink, of ideas bound in hardback.

As far as I could tell, the ex-library was being used as an improvised and not quite official workshop for restoring murals. Six or seven long tables ran the length of the first floor, and on them lay the panels of a mural from the 1930s, painted by Ramón Alva de Canal and called The History of Writing.

A small, suspicious, mousy man—the “Workshop Director,” according to the nametag pinned to his shirt—came up to chase me away as soon as he saw me cross through the arched entrance accompanied by one of the two guards. But the squat angel in blue, now on my side, immediately vouched for my good intentions: The señorita says she’s come to see you, chief.

Each section of the mural recorded a different moment in the graphological history of mankind, beginning with a simple image of the first tremulous strokes on the wall of some cave, and ending with a sort of strident hymn to the great industry of the modern press. It seemed a little ironic that this very mural, The History of Writing, was being restored in an ex-library completely devoid of books. The image of the empty, dilapidated library housing this mural, itself in a ruinous state, should have perhaps made up the seventh, nonexistent panel to complete the series:

1. Cave painting

2. Cuneiform writing

3. Papyri and hieroglyphs

4. The alphabet

5. Johannes Gutenberg

6. Modern printing

7. The fall of libraries and bookshops

No Parking

In the middle of a sentence, after the umpteenth comma deleted and undeleted, I suddenly lose the will to continue writing. I get up from the desk, impatient and defeated, and go to the bookcase. With the persistence of a mosquito around a lightbulb, I prowl the shelves in search of that book, that page, that underlined phrase I vaguely remember, but which—if I could only reread it—would finally give me the confidence to complete my recently abandoned idea. But I find nothing and sit back down at my writing desk.

I know that the times I feel most excited about what I’m writing are when I should be most suspicious, because more often than not I’m repeating something I either said or read elsewhere, something that has been lingering in my mind for a while. I’m almost always saying something trivial just when I believe I’m on the verge of a novel idea. In contrast, the worst moment to stop writing is when I no longer feel like going on. On those occasions, it’s always better to keep rapping thoughts into the keyboard, like drilling holes in the ground, until the exact word emerges. Only then, take the book off the shelf and drop into an armchair to read. In some way, I guess, writing is making space for reading.

We Buy Old Books

Cities have often been compared to language: you can read a city, it’s said, as you read a book. But the metaphor can be inverted.

The journeys we make during the reading of a book trace out, in some way, the private spaces we inhabit. There are texts that will always be our dead-end streets; fragments that will be bridges; words that will be like the scaffolding that protects fragile constructions. T. S. Eliot: a plant growing in the debris of a ruined building; Salvador Novo: a tree-lined street transformed into an expressway; Tomás Segovia: a boulevard, a breath of air; Roberto Bolaño: a rooftop terrace; Isabel Allende: a (magically real) shopping mall; Gilles Deleuze: a summit; and Jacques Derrida: a pothole. Robert Walser: a chink in the wall, for looking through to the other side; Charles Baudelaire: a waiting room; Hannah Arendt: a tower, an Archimedean point; Martin Heidegger: a cul-de-sac; Walter Benjamin: a one-way street walked down against the flow.

And everything we haven’t read: relingos, absences in the heart of the city.

Guaranteed Repairs

Restoration: plastering over the cracks left on any surface by the erosion of time.

Sidewalks

Writing: an inverse process of restoration. A restorer fills the holes in a surface on which a more or less finished image already exists; a writer starts from the fissures and the holes. In this sense, an architect and a writer are alike. Writing: filling in relingos.

No, writing isn’t filling gaps—nor is it constructing a house, a building, just to fill up an empty space.

Perhaps Alejandro Zambra’s bonsai image might come closer: “A writer is a person who rubs out. . . . Cutting, lopping: finding a form that was already there.”

But words are not plants and, in any case, gardens are for the poets with orderly, landscaped hearts. Prose is for those with a builder’s spirit.

Writing: drilling walls, breaking windows, blowing up buildings. Deep excavations to find—to find what? To find nothing.

A writer is a person who distributes silences and empty spaces.

Writing: making relingos.

•

Valeria Luiselli was born in Mexico City in 1983 and grew up in South  Africa. Her novels and essays have been translated into many languages and her work has appeared in publications including the New York Times, Granta, and McSweeney’s. Some of her recent projects include a ballet libretto for the choreographer Christopher Wheeldon, performed by the New York City Ballet in Lincoln Center in 2010; a pedestrian sound installation for the Serpentine Gallery in London; and a novella in installments for workers in a juice factory in Mexico. She lives in New York City.

Africa. Her novels and essays have been translated into many languages and her work has appeared in publications including the New York Times, Granta, and McSweeney’s. Some of her recent projects include a ballet libretto for the choreographer Christopher Wheeldon, performed by the New York City Ballet in Lincoln Center in 2010; a pedestrian sound installation for the Serpentine Gallery in London; and a novella in installments for workers in a juice factory in Mexico. She lives in New York City.

Christina MacSweeney has an MA in literary translation from the University of East Anglia and specializes in Latin American fiction. Her translations have previously appeared in a variety of online sites and literary magazines. She has also translated Valeria Luiselli’s novel, Faces in the Crowd.

One thought on “Relingos”