Watchlist: 32 Short Stories by Persons of Interest

Edited by Bryan Hurt

372 pages

Paperback: $20

E-book: $10

ISBN 9781939293770

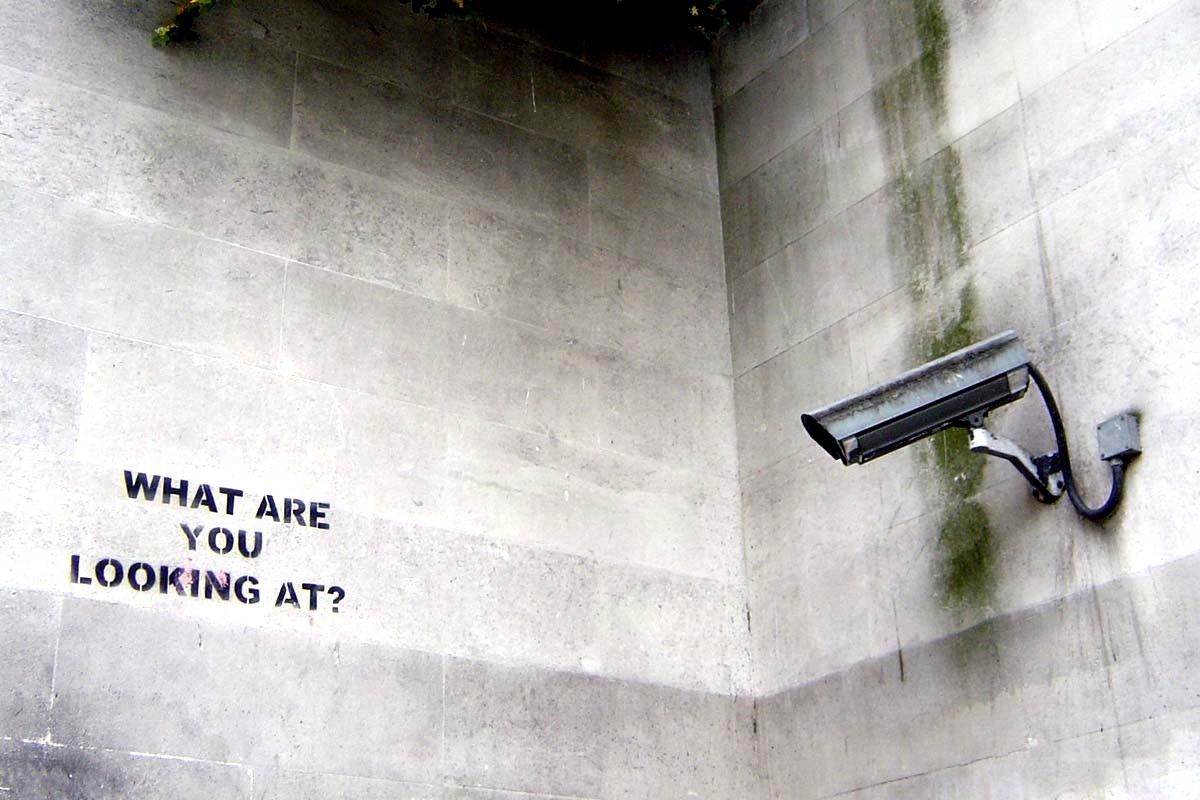

Bryan Hurt’s introduction to the short-story collection Watchlist begins with the moment that he and his wife first wonder if their baby monitor isn’t a form of “spying.” The idea prompts him to consider the extent to which we are aware of being observed by our governments—and to marvel at how little that awareness seems to affect us as a society. In the end, he advises his son to “get used to it, little dude,” because “being watched is part of life.”

A part of life, but nevertheless a disorienting one, according to Watchlist’s “32 stories that reflect on what it’s like to live in the surveillance state.” The pieces in Watchlist that most directly address state surveillance tend to highlight the absurdity lurking in repression. The web-watching spies of the unnamed empire in “Terror(tour)istas” (Juan Pablo Villalobos) work feverishly to decide if people posting and liking poetically captioned photos of K2 on Facebook (“Mountains are not fair or unfair…”) should be arrested and tortured, or spammed with ads for exotic holidays. In “Our New Neighborhood” (Lincoln Michel), Donald creates a mini-surveillance state (complete with drones, dissidents, conspiracies, and so on) in his suburb of Middle Pond—“located between West Pond on the east and East Pond on the west”—because he is obsessively worried about property values.

This emphasis on the absurd might be a matter of taste: Hurt’s preference, at least in Watchlist, is apparently for absurdist stories of the type misleadingly known in American indie publishing as “innovative fiction.” The association of absurdity and authority also might be an expression of how Hurt perceives government. If so, he would be in good company: political satire has always assumed that one can (and should) bring rulers nose-to-nose with the ridiculous. The pieces collected in Watchlist do not necessarily make clear, however, whether logical absurdity leads to the surveillance state or the other way around. Meanwhile, their conflation in some stories apparently means that absurdity by itself inevitably implies repression.

A similar conflation of subjects happens around technology. Almost every story about state spying shares a distrust of technology. Although government is sometimes the main culprit, tech companies inevitably provide the tools. Google and Facebook make several appearances, joined by a long list of invented start-ups and their apps and hardware: Ether, FicShare, HausFlippr, SingleMingle, Olfanautics, Ladykiller, Strava—technology is what makes surveillance both likely and possible.

By extension, it seems, all new technology must be a form of surveillance. “The Relive Machine” (T. Coraghessan Boyle) and “Second Chance” (Etgar Keret) are both stories about new technology in which people watch only themselves: owners of relive machines can visit their own pasts through stimulation of their memories; clients of the Second Chance service can, at the moment of death, experience a virtual second life based on one decision made differently. “The Transparency Project” (Alissa Nutting) is told by a woman who allows researchers to replace part of her skin with a clear plastic so they can observe her organs. What has any of this to do with the surveillance state?

Either way, the (im)morality of surveillance is decided long before the story begins. Watchlist never seriously entertains, let alone grapples with, the idea that surveillance might sometimes serve a purpose. Only in “Safety Tips for Living Alone” (Jim Shepard), about the doomed crew of a poorly conceived Cold War radar station in the North Atlantic, can one find anything like a plea for more watchfulness: “How did everyone let things get to this point?” a wife asks when her husband, facing death in the station’s inescapable collapse, calls her for the last time.

Because no piece in Watchlist seeks to explore the desires and fears that bring about surveillance in the first place, the collection overlooks how democracies become surveillance states. After 9/11, Americans overwhelmingly called for “vigilance” over privacy, just as earlier generations had during successive Red Scares—and yet the villain of the stories in Hurt’s anthology is hardly ever “we.” Instead, it is almost always a nonspecific and thus de-humanized “they,” and Watchlist shies away from examining the extent to which “we” have chosen to give “them” their power.

The editorial approach of theme-by-association at first obscures this issue. In most cases, the stories Hurt has assembled offer no clear connections to state surveillance at all, or only the most tangential—suggesting he prefers to define “surveillance state” as broadly as possible. Many stories relate one person’s watching of another, stretching as thin as possible any relationship to intrusive government. Tucker in “The Taxidermist” (David Abrams), for example, uses his sixth sense to spy on his ex, and doesn’t like what he sees; the state is not even a distant concern.

The relationship between Hurt’s chosen stories and state surveillance is even harder to establish in “Buildings Talk” (Dana Johnson), in which the narrator meets his building’s recently fired super at a bar, or “What He Was Like,” Alexis Landau’s story told from the point of view of a woman who suffers a miscarriage and finds it hard to open up to others. Stories such as these can leave the reader scrambling for some hidden link to the collection’s stated purpose, to “reflect on what it’s like to live in the surveillance state.” Was the sonogram surveillance? The narrator’s fear of the evil eye? In Shepard’s “Safety Tips for Living Alone,” radar, presumably, is the vehicle of surveillance—or is it?

To the extent that one might possibly describe the opening vignette, Robert Coover’s “Nighttime of the City” (with its dozens of gun-toting, cigarette-smoking automata in hard-boiled detective gear), as being “about” anything, surveillance comes well below, say, gender in genre fiction, the glorification of violence, and the dangers (or is it pleasures?) of tobacco. Similarly, Bonnie Nadzam’s “The Witness and the Passenger Train,” in which scientist couple Dr. Flame and her husband Dr. Flame travel to space to visit a constellation they themselves may have caused to exist, doesn’t have anything obvious to do with either government or surveillance—unless one counts the presence in the story of a telescope.

It is of course interesting, as the surveillance state expands, to investigate an expanded definition of surveillance itself (does looking in the mirror count? what about letting someone take your photo?)—but to define the term so loosely that it can include anything is ultimately to render it meaningless. Such a definition serves above all to emasculate dissent: if nostalgically recalling your college love-life is surveillance, civil libertarians are opposed to nothing less than human nature. To struggle is useless. What is the surveillance state according to Watchlist? As Bryan Hurt might ask: Dude … what isn’t?

.

Tadzio Koelb has lived in France, Spain, England, Rwanda, Madagascar, Tunisia, and Uzbekistan. His writing has appeared in the Brooklyn Rail, the New York Times, the Times Literary Supplement, the Guardian, Art in America, the New Statesman, and elsewhere. Morasses, his translation of André Gide’s Paludes, will appear this summer from Calypso Editions. He teaches creative writing at Rutgers and is a deputy managing editor at The Brooklyn Quarterly.

Tadzio Koelb has lived in France, Spain, England, Rwanda, Madagascar, Tunisia, and Uzbekistan. His writing has appeared in the Brooklyn Rail, the New York Times, the Times Literary Supplement, the Guardian, Art in America, the New Statesman, and elsewhere. Morasses, his translation of André Gide’s Paludes, will appear this summer from Calypso Editions. He teaches creative writing at Rutgers and is a deputy managing editor at The Brooklyn Quarterly.