This week, TBQ spoke with Steven G. Fullwood, Assistant Curator of the Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library. Fullwood talked about his most recent curatorial project, Black Powered: Amiri Baraka In Memoriam, an exhibition at the Schomburg Center open now through Monday, February 10. Find more information on visiting here.

TBQ: You curated Black Powered: Amiri Baraka In Memoriam, a pop-up exhibit at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. What inspired your vision for this exhibition, and how did it come together? Why do it as a pop-up?

Amiri Baraka is one of the most influential and prolific writers and activists of the twentieth century. Not marking his passing would be tragic. [Baraka passed away on Jan. 9 in Newark, NJ – you can read TBQ’s remembrance of him here]. That said, the Schomburg Center is the perfect space for such an event. Our supreme charge is the preservation of culture and history for people of African descent. We collect, preserve, and provide access to a wide range of materials for all levels of research and for public programming.

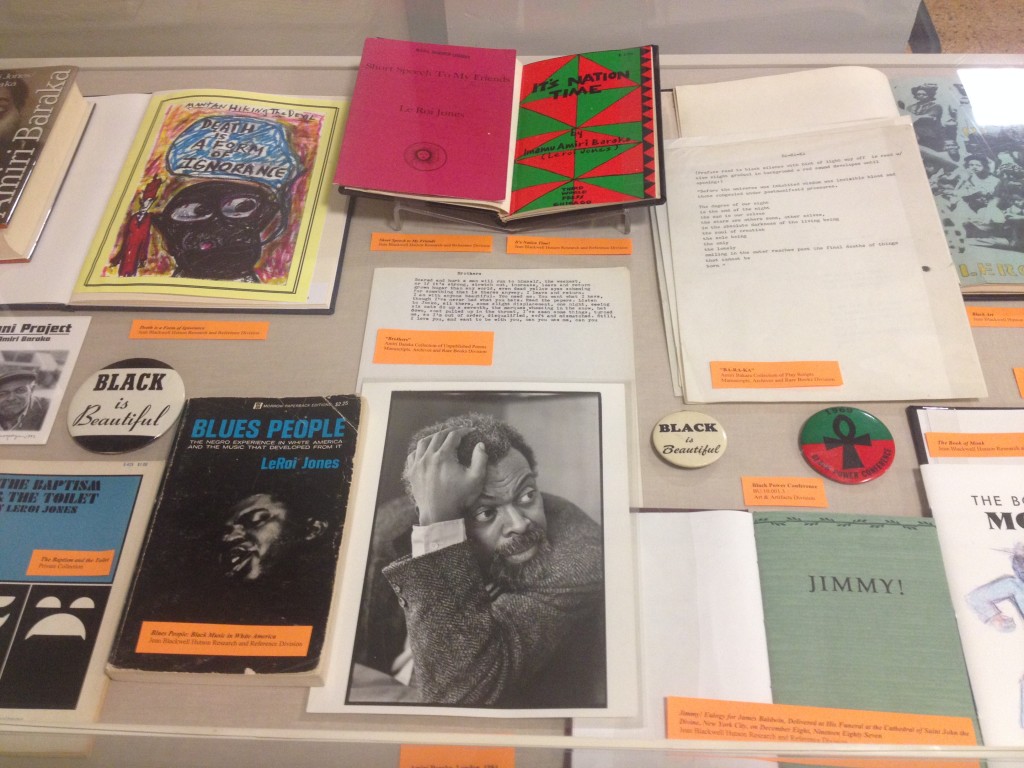

The Schomburg holds materials produced by and about Baraka—books, film, photographs, art work, etc.—and putting together this exhibition was a no-brainer. Personally, I wanted to honor him because of the impact he’s made on American letters and in my own life and work, beginning in college when I read plays such as Dutchman and The Toilet, poems such as “Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note,” and short story collections such as Tales of the Out & the Gone. Baraka taught me to value my own experience and write the way I wanted to, and to be useful to the communities I serve. I’ll always be grateful for his agitating presence in my literary imagination.

As you can imagine, exhibitions can take anywhere from six months to a year or more to plan and execute. Pop-up exhibitions are usually inspired by a particular moment—sometimes, unfortunately, by the passing of a monumental figure like Nelson Mandela. It is a comparatively easier way to pay tribute to a person or significant moment (for example, the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom) in a relatively short amount of time. I feel that reading a book, taking in a film or seeing a photograph can be transformative for those who remember, for those who don’t, and for those being introduced to a person, place or event for the first time. This is the power of history in action.

TBQ: The Schomburg Center is also co-producing a musical event with the National Black Touring Circuit in conjunction with Black Powered. Can you tell us more about this upcoming performance, and how music fits into your ambitions for the exhibition?

A Tribute to Amiri Baraka, initially conceived as a tribute to Baraka, is now a memorial. The program features writers Haki Madhubuti, Sonia Sanchez and Quincy Troupe, as well as musician Randy Weston, all of whom knew and/or worked with the late poet/activist/thinker. In addition to hundreds of poems and plays, Baraka was an able critic who produced the social-aesthetic study of African-American music Blues People: Negro Music in White America. It’s fitting that he should be remembered in a musical poetic tribute, because blues and jazz music informed his writing from day one.

While the Schomburg has housed performances by Baraka over the past few decades, many of which contain music, Black Powered: Amiri Baraka In Memoriam features the CD jacket for The Shani Project, a poetic musical performance by Amina and Amiri Baraka that is dedicated to their daughter Shani, who was killed in 2003.

The exhibit is intended to remind those visiting the Schomburg, as well as those people in attendance for the program, of Baraka’s genius, in a visual sense. For nearly five decades, Baraka tirelessly published his work, was active in political movements, and became an elder statesman who wasn’t afraid to challenge the status quo, or to change his own views.

TBQ: One thing that really struck me about the description for this exhibition was its variety and inclusiveness. I came away with the impression that Black Powered has something to offer to both longtime readers and newcomers to Baraka’s work. Without giving away spoilers, what aspects (or items) included in Black Powered are closest to your heart and mind as a curator or as a reader?

I became aware of and entranced with LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka in college, when I was a struggling student seeking to fulfill a desire for clarity of purpose. I was the product of the Civil Rights Movement, a first-generation college student, a burgeoning homo. The Toilet is one of my favorite plays for its sensitivity and recognition of violence, desire, and perceived differences. There are other wonderful items in the exhibition, particularly a photo of Baraka in Cuba with a delegation of black writers and thinkers, including historian John Henrik Clarke. Taken as a whole, the exhibition is a dazzling display of what I call Barakaspeak: loud, loving, dazzling, critical, and often humorous, but always on time and necessary. Black Powered showcases a sample of Baraka’s published and unpublished work, images of the iconic writer, and other interesting items. It is a privilege for me to honor him in this way.

TBQ: Would you do an exhibition like this one again? Do you have plans for future pop-ups or programming devoted to Amiri Baraka?

Oh, absolutely. Other than A Tribute to Amiri Baraka, I am not sure what’s being planned at the moment, but it’s good to sign up for Schomburg Center’s news blasts here to keep informed about our stellar programming.

Photo credit: Joel Diaz, Education Associate, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture