NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell at Super Bowl XLIII. Picture by Staff Sgt. Bradley Lail, USAF (via Wikimedia)

The storm of football-related violent crime this year is pushing questions about the sport’s troubled relationship with domestic violence into the national consciousness. Now the National Football League is on its heels after being out-maneuvered by almost everyone in America and risks losing sponsors, which is the only wake-up call it will heed. I will leave the broad-scale social commentary to others, but have noticed several aspects of the league’s response to its players’ behavior that deserve scrutiny.

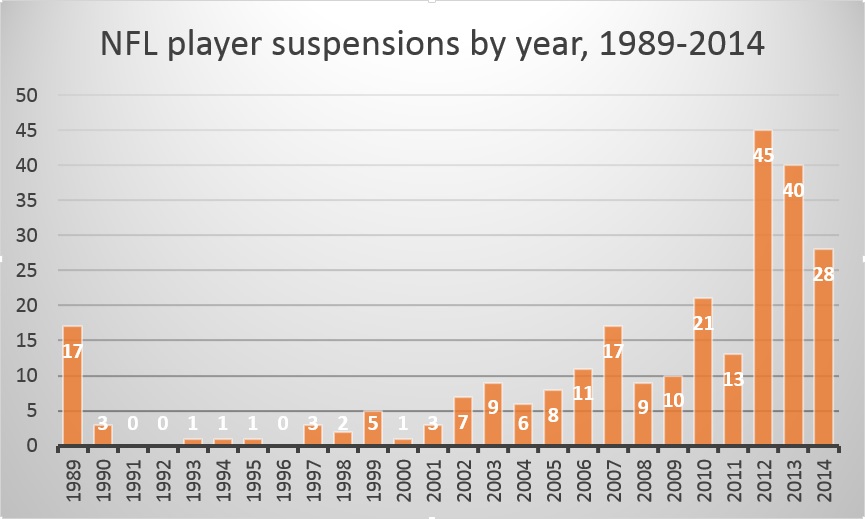

Thanks to research by Allison McCann at FiveThirtyEight, TBQ was able to tease out some takeaways from the data. McCann’s article pointed to the distributions of suspensions the league has handed out for conduct and drug violations. Even aside from the astoundingly trivial suspensions it has issued for terrible crimes (not to mention all those that went unpunished), the data raise several unanswered questions.

First, has the league’s problem with gambling ended? The first five suspensions, from NFL’s early days through the early 1980s, were for associating “with known gamblers.” That’s when those suspensions cease, however. It is hard to believe that no players have spoken with known gamblers—a behavior sufficient for suspension in the league’s first four decades—since 1983.

Second, how will the next collective bargaining agreement, or CBA, with the players’ union (the current one began in 2011 and runs through 2020) deal with drug laws? Last year’s Super Bowl teams—the Seattle Seahawks and Denver Broncos—both play in states where marijuana is now legal. More states are to follow.

Third and most importantly, what is behind the enormous surge in suspensions in the last 25 years? The rate of suspensions skyrocketed in 1989, the year Paul Tagliabue succeeded Pete Rozelle as commissioner. It is possible that suspensions were simply Tagliabue’s preferred response, and that Roger Goodell has continued that policy. However, even the elevated rate of suspensions under Tagliabue, just under 4 per year, jumped to almost 22 each year since 2006, when Goodell took over. (Keep in mind there’s still more than one-quarter left of 2014.)

Source: FiveThirtyEight

So what has changed to prompt such a huge shift in the last decade? Have players become more violent at home? Have they started doing more drugs? Have they started taking more steroids? Not likely.

It is possible that the NFL has caught up to the players in terms of performance enhancing drugs, particularly since the new CBA came into effect. But that explanation does not account for the league’s reactive policies to its ongoing head-injury scandal. In addition, how players behave at home is still beyond the grasp of league administrators, much to the league’s chagrin.

One thing that has changed since 2006 is the role of the internet. Just as online fantasy football has done arguably more for the growth and popularity of the game than any NFL commissioner could, online reporting outlets like TMZ and Deadspin have become the policing mechanism that the league lacks.

It’s clear that Roger Goodell needs to resign or be replaced. It’s also clear that cutting down on domestic violence among professional football players won’t stop abuse nationwide. But it is apparent that actors outside the commissioner’s office might force the league’s hand. It is promising that with today’s constant media cycle, the league and its players will be held to higher standards of transparency and accountability.

Below is an interactive timeline of NFL player suspensions since 1946.

Neil Reilly is a TBQ Blog Editor. He works as a policy analyst at Citizens Housing & Planning Council, and writes on data and urban social policy matters.

Neil Reilly is a TBQ Blog Editor. He works as a policy analyst at Citizens Housing & Planning Council, and writes on data and urban social policy matters.