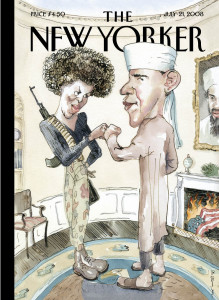

Satire has been a controversy-prone genre for hundreds of years, and every once in a while, a new joke will cause enough trouble to bring up questions about its limits. During the 2008 presidential elections, The New Yorker sparked a public outcry when an illustration depicting the Obamas as an evil-grinning, flag-burning, fist-bumping, weapon-toting Muslim couple graced the magazine’s cover. Last year, The Onion received intense criticism after a joke calling then-9-year-old actress Quvenzhané Wallis a “cunt” was published on the site’s Twitter account. Most recently, Suey Park, an Asian American activist, questioned Stephen Colbert’s satirical racial humor by starting the #CancelColbert hashtag, which quickly went viral and sparked a national debate.

Unfortunately, the discussion of satire never seems to go that far. What has happened in these situations so far is anyone offended by a satirical joke is labeled as either too stupid to understand intellectual humor or too miserable to find anything funny about it. Everyone who finds the satirical joke in question hilarious then packs up and goes home.

On its face, being offended by a satirical joke while fully understanding its intent might seem baffling. Most people opposing Suey Park are unable to make sense of her persisting qualms regarding Colbert’s racial humor when combined with her insistence that she does, in fact, understand satire. It seems only two options are possible in the minds of her critics: Either she understands that Stephen Colbert plays a parody of a bigoted, idiotic Republican and embraces his racist jokes as funny, or she’s an airhead who’s taking Colbert’s persona literally and is getting offended as a result.

But it’s not as simple as that. While there were many Asian Americans who strongly opposed Suey Park and let everyone know that they found Colbert’s joke hilarious, there were also Asian Americans who supported Park. This goes for every group that’s targeted by satirical humor. Not all women are going to be bothered by satirical sexism, not all Latinos are going to care about satire poking fun at us, and so on and so forth. It’s condescending to dismiss everyone who has issues with racial jokes made in the name of Satire as dumb or hopelessly bitter.

Jokes get tiring

President Obama fully understood The New Yorker’s intent when they published the over-the-top caricature of him—they meant to mock the extremist right-wing propaganda going around claiming he was a Muslim and a traitor to his country—yet he still didn’t think it was funny and neither did his campaign administration. Barry Blitt, the cartoon’s artist, and David Remnick, The New Yorker’s editor, both defended the cover, insisting that the exaggerated nature of the cartoon’s details would immediately make its targets of ridicule obvious, especially to the The New Yorker’s intellectual audience.

President Obama fully understood The New Yorker’s intent when they published the over-the-top caricature of him—they meant to mock the extremist right-wing propaganda going around claiming he was a Muslim and a traitor to his country—yet he still didn’t think it was funny and neither did his campaign administration. Barry Blitt, the cartoon’s artist, and David Remnick, The New Yorker’s editor, both defended the cover, insisting that the exaggerated nature of the cartoon’s details would immediately make its targets of ridicule obvious, especially to the The New Yorker’s intellectual audience.

While it might be true that most readers of The New Yorker would get the joke, the cartoon on its own isn’t as obviously satirical as Barry Blitt and David Remnick would like to think. The Internet is flooded with hundreds of thousands of cartoons equally—and even more—over-the-top than the one they put on the magazine’s cover. There are endless drawings, paintings, and Photoshopped images depicting the Obamas as apes and terrorists. Almost all of them are made by conservatives whose intent is nowhere near attempting to make a satirical statement about racism. During election season, it wasn’t uncommon to see the anti-Obama crowd carrying signs, wearing shirts, and chanting all sorts of racist diatribe. And none of that has stopped after his election—there are people today who love to refer to Obama as “Primate in Chief.”

So Barry Blitt’s artwork, as ridiculous as it was, was not visually different from the racist propaganda it was attempting to mock. A common counter-argument to this is that the intent behind The New Yorker’s cover differentiates it from the purposely malicious racist content being thrown at Barack Obama and his family at the time. That might also be true, but it was probably tiring for President Obama and his administration to see a national magazine trying to defend him against vicious attacks by using similar imagery. After having to deal with opponents throwing that type of material around constantly, it would’ve been nice if a magazine that was attempting to be an ally in the situation had used a different tactic. Of course I don’t know if this specific line of thinking is what led to President Obama and his campaigners finding the cover distasteful. However, if one searches back through articles of the time, it won’t take long to find comments expressing similar sentiments. Latoya Peterson wrote a piece on Racialicious in 2008 discussing the subject.

Making people who are discriminated against caricatures

It’s easy to laugh at Stephen Colbert’s character because he’s embodying the persona of a privileged person: white, male, straight, Christian, and at the very least upper middle class. He’s not a member of any demographic that would feel oppressed by any of the jokes he makes mocking his own race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, or class. Satire gets trickier when the group or person who’s turned into a caricature is actually part of a marginalized group, such as in The New Yorker’s cover. The people we’re mocking—racist conservatives—are invisible, which is the opposite of what usually happens in The Colbert Report.

This was precisely the reason why so many people found The Onion’s satirical tweet calling Quvenzhané Wallis a cunt reprehensible. Regardless of whether or not the joke was satirical, it doesn’t make the scenario of explaining to a little girl that she was jokingly referred to by one of the worst sexist slurs any less uncomfortable. Quvenzhané was facing real-life backlash for having an “attitude problem,” particularly after she asked a reporter to call her by her real name when he declared that he was going to call her “Annie” because it was easier to pronounce. At nine years old, Quvenzhané was not only being put under the intense likability microscope reserved for women, but she also had to deal with Hollywood beauty standards that praise whiteness and found that her hair and its natural or straightened state were a constant point of conversation. She had to deal with multiple instances of blatant rudeness and disrespect at the Oscars, where she was one of the youngest nominees in history.

When grown adults are bashing a 9-year-old’s character, it’s not funny to make a satirical joke calling her the c-word. We don’t how much media Quvenzhané Wallis consumes and how oblivious or informed the adults around her keep her about these sorts of controversies, but I have to wonder how the conversation would have gone down if she had been informed. Did they say, “Don’t worry Quvenzhané, The Onion doesn’t think you’re cunt, they’re just making fun of all those other people who think you’re a cunt. What’s a cunt? Well, it’s a little worse than being a bitch.”

If whoever was running The Onion’s Twitter feed felt that strongly about making fun of Quvenzhané’s critics, they could’ve done it by centering the joke around those people. Why not make a satirical joke targeting the red carpet reporter who wanted to call her Annie? It wouldn’t be that difficult to come up with a crack about someone whose basic job is to memorize actors’ names and make small talk about their movies, and can’t even get the name part down.

By creating satirical caricatures of the people who are harming others instead of those who are being harmed, there’s also less of a chance that you’ll inadvertently promote what you’re attempting to criticize. A lot of people claimed to understand The Onion’s joke, but there were a lot of people out there who were laughing in a “it’s funny because it’s true” way. Same with the caricature of the Obamas on The New Yorker—plenty of racists loved it for all the wrong reasons. Is satire effective when the people you’re hoping to slap in the face with their ridiculousness don’t get it? The Colbert character is an over-the-top mirror image of conservatives and bigots. He gets under Republicans’ skins because they’re recognizing themselves as mocked caricatures. This is much more effective than handing out ridiculous depictions of people they, the conservatives, hate.

On Colbert’s specific brand of satire

Full disclosure, I’m a huge Colbert fan. I’ve been watching his show for years, I’ve bought his books, I watch his epic roast of George W. Bush at least once a month, and I even went to the January 12, 2010 taping of his show. His satire is usually on point for me, but I still acknowledge that his show isn’t perfect.

Like he mentioned during his rebuttal of #CancelColbert, he’s received criticism from the Asian American community before for an Asian character he plays on The Colbert Report named Ching Chong Ding Dong. His performance involves squinting his eyes, moving slowly, and speaking with a stereotypical Asian accent. This isn’t the only character Colbert plays on his show who’s of another race or ethnicity—there is also Esteban Colberto, a Mexican version of Colbert who occasionally shows up to talk about Latino issues. He’s always accompanied by a dancing “chica” on each arm, while they dance to Cuban music playing in the background. In some clips, Colbert has clearly bronzed his skin to look the part, which is both offensive and unnecessary as there are extremely pale Latinos out there (myself included).

As with Ching Chong Ding Dong, the thing that makes Esteban Colberto so hilarious is his ethnicity. We laugh at his dancing, at his funny accent, at terms like “chupa-bias.” Unlike the Stephen Colbert character, whom we laugh at for being an narcissistic, deluded idiot, we laugh at Esteban Colberto because all his Latin quirks are hilarious.

I don’t particularly care that much about the Esteban Colberto character, but his presence does make me think about Suey Park’s assertion that some racial and ethnic groups are “safer” to use as punchlines. While Colbert often makes jokes involving African Americans and other black groups, it would never in a million years occur to him to play a black character on the show involving getting in blackface and talking about watermelon and fried chicken. Satire or not, he and his writers would never dare tread that territory, which is why it’s so interesting that other groups are still up for grabs for this sort of humor. Of course, the history of minstrelsy and stereotypes surrounding African Americans in the United States is much different than that of groups that might be seen as “newer” here. However, it’s still worth thinking about. It shouldn’t be okay to transfer racist jokes from one minority group to another just because the first group is no longer going to quietly accept it.

The reaction many of Colbert’s defenders had in response to Suey Park’s criticism was more intense than the situation warranted. It should never be acceptable for a professional journalist to call a person he’s interviewing “stupid.” During the height of the #CancelColbert controversy, there was article after article being written to convince everyone that Suey Park was not a credible person to listen to, as well as pieces dedicated to simply attacking her character and calling her “crazy.”

Whether or not one finds Colbert’s satire, or any person’s satire, objectionable, acknowledging that someone could possibly have a valid reason for finding it so shouldn’t be so terrible. There are valid reasons to find satire hilarious, just as there are valid reasons to find it questionable. I don’t know what the solution here as far as what should be “done” about satire would be, but a discussion should at least be possible. The debate shouldn’t always have to end with, “If you don’t think it’s funny, you just don’t understand it.”

One thought on “On Satire and the Unique Brand of Controversy It Breeds”