I was recently at my high school reunion where, upon hearing my answer to the inevitable “So what are you doing these days,” I was asked if I was “for real” and “like, not lying.”

My great stumper of a response? That I am a city planner, specifically, in Saint Paul, Minnesota, which is approximately 1,200 miles from my native New York.

The city planner is an elusive animal. The name seems to be at once almost comically self-explanatory, while remaining almost equally opaque by virtue of its vagueness. City planners are often government officials (though they aren’t elected), and they deal with those most intimate questions of figuring out how to make neighborhoods places where people actually want to live, and, ideally, be able to do so for a long time. This is not so easy.

Cities are back, in a big way. Millennials love them; boomers love them. They’re increasing in population, and becoming more diverse. (This is not unique to America; more than half the world’s population has been living in cities for a number of years now, so, 3.5 billion people are probably onto something.) People aren’t buying cars the way they used to, bikes have become hot and the stigma of riding public buses is falling under scrutiny. Reports show that millenials value access to good public transportation. And someone needs to, you know, plan for all these things.

The trouble is, the last few generations didn’t adequately anticipate the huge boom in urban popularity. Walkable urban neighborhoods are all the rage. You know them: they the ones your friends take you to when you visit them, where you can maybe go shopping, go to a coffee shop, take in a movie, or go out to eat—all in one neighborhood. These are places where there is usually a sense of history, where you don’t need a car to get around, where you can actually live your entire life within a few blocks. These neighborhoods save you time and car trips, and they encourage human interactions. So it’s no surprise that there is now a 25-30 percent gap between the availability of housing in these areas, and the demand (which is probably why my apartment’s rent keeps going up).

Walkable neighborhoods aren’t just for hipsters either. The average cost of car ownership has hovered around $9,000 per year for the past few years — a huge burden on citizens with low income, and money that could be spent in our local economies instead. But these neighborhoods exist sporadically in most cities, and not at all in most suburban or exurban communities, which is the unfortunate but logical conclusion of years of poor planning.

For years, urban planning centered on cars, and the automobile was the crux of American lives. It made sense, on some level, to plan communities of big houses with vast front yards and no sidewalks. Shopping became clustered in strip malls hidden behind seas of asphalt, and work became a place to which the single breadwinner would drive an hour or so in order to leave his car in a parking lot, deck, or garage.

That world is changing. More families have (and must have) dual incomes; global warming is increasingly recognized as a “real thing” (according to my coworker who nevertheless burns more than an hour and a half’s worth of gasoline to work each way every day); and the embrace of urban activities, such as walking and biking, dovetails nicely with initiatives to combat our national obesity epidemic.

So how do we adapt to meet the new needs and new desires of the next generation, and to plan for the future of our communities? What can help close the gap between supply and demand for urban living? How can we increase the number of neighborhoods that, beyond being popular right now, are more economically and environmentally sustainable in the long run? How can we account for the future of all those people moving into our communities, and for our children, and their children?

Solutions exist, but they are hard. Because what’s difficult to grasp as you’re waiting for that bus or train that feels like it’ll never show up, is that city planning is a constant exercise in contradictions: cities can take upward of a century to plan, and getting things built inevitably takes time, and yet, cities can change seemingly overnight.

ABOUT CITY PLANNING

Wrangling a beast as nuanced as a city requires a lot of interdisciplinary skills. I see the job as a unique intersection of civil engineering, politics, design and common sense—but that’s a bit unwieldy. For starters, there’s a whole host of what city planners may do. We city planners are all up in your local government, setting your zoning codes, approving your developments, improving your mobility, and regulating your environment.

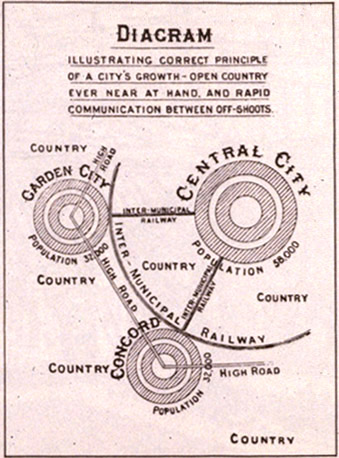

Lorategi-hiriaren eskema, 1902. Photo by Ebenezer Howard, Wikimedia Commons.

Planners may “plan” land use, parklands, transportation and other infrastructure. Planners work in myriad public agencies and departments, for private development companies or consulting firms, and at non-profit and advocacy organizations. They work on everything from environmental conservation to industrial expansion to economic development to historic preservation. But most of us do a mix of those initiatives, and all of us have to think about (if not balance) all those needs and so, so many more.

Planning also has a stronghold in the academic world. The differences between theory and practice can be stark. Some find research and comparative study preferable to the messiness of daily city politics. Like most city planners, I have a master’s degree in city planning, and I see principles from the academic world in subtle action in my job. And like most planners, I find the elegance of academic theory all too frequently buried under the endless tangle of city politics — something grad school will never prepare you for.

As City Planner for the City of Saint Paul’s Department of Planning and Economic Development, I focus on transportation. In the past two years, I’ve led a streetcar feasibility study, worked on a bike plan and street-design manual, and collaborated with staff from other communities in the region on our collective transportation policy plan. In practice, what does this look like? Today, for example, I spent most of my day in meetings—arguing over charts and tables, nitpicking text and working out differences in priorities—and getting ready for next week’s meetings with community groups. Then, I went to a public meeting where I presented the results of a feasibility study to a community organization and was told, point blank, that I was trying to ruin this city and the lives of everyone who lives and works here and why don’t I just reach into their pockets and steal their money directly because that is all I’m doing in my job.

No matter what you do in planning, someone is going to hate it. We are the professionals and the faces of the policies that have the power to make dramatic changes to the people who live in the communities where we work. But the public participation process is everything: we all do this work to improve people’s lives, so it’s essential to work with the public to understand how best to do that. Unfortunately, everyone has a different idea of what that means, and our job is to make sense of it all.

So we form task forces, we host forums and panels, we put on town halls and focus groups and take to the Internet for message boards and e-mail conferences. We reach out to interest groups, business associations and neighborhood activists—and everyone who’s ever expressed an opinion before, and that is a lot. (There is this term, NIMBY, which stands for Not In My BackYard. I’ll leave you to your imagination). We develop thick skins and a strong stomach and try to cultivate irrepressible optimism and confidence that the work we’re doing is going to make a difference.

Then we go incorporate expert studies, or casework, or comparative research into the raw input of all those people enumerated, putting all that grad school to good use. Finally, taking into account all of that and best practices in the field, we make a recommendation. Sometimes it seems simple, and sometimes we have lots of support; sometimes we get protesters and get cursed at in public forums. Sometimes you can convince policy makers that what we’ve researched and proposed is the best option, and that they should devote staff time and resources and — oh, yeah— money, to that cause. And sometimes, sometimes, we can get things — real things — done.

Talking about the results of the Saint Paul Streetcar Feasibility Study with a community member at the Great River Gathering. Photo by Jeff Syme.

THE LONG TERM

In 1910, a bold vision was published in local papers of the Twin Cities. Minneapolis and Saint Paul each had a growing downtown. Residential neighborhoods were thriving along streetcar lines that crisscrossed the region. These vehicles were slow, running in the same roadways as horse-drawn vehicles, stopping sometimes every block. A rapid connection between the two downtowns would knit together the economies of the Twin Cities and encourage denser development between them, fostering economic activity and attracting more housing for their workers.

It was a splendid vision for the future. Unfortunately, for more than a century, the present got in its way.

Planning is about anticipating the future of our communities and respecting and reflecting on their pasts, while meeting the needs of the present. Approaches to urban planning are, therefore, always shifting; they express the diversity and change of the cities they are trying to serve. Each city, too, has its own personality and needs that can’t be addressed with a one-size-fits-all policy.

Saint Paul, Minnesota belongs to the ranks of what are often thought of as “second” cities; like Brooklyn to Manhattan or Providence to Boston, there is a certain self-consciousness in Saint Paul’s relationship to its larger neighbor. (That would be Minneapolis. They aren’t called the Twin Cities for nothing.) But while both Minneapolis and Saint Paul are cold, snowy, long-wintered (and did I mention cold?) cities, even twins have distinct identities. Saint Paul is hillier, for one thing. It prides itself on its smaller population, its long-standing and close-knit residential communities, and its smaller-scale commercial districts. Saint Paulites see Minneapolis as the more modern, flashier city. There’s a geographic distinction, too: situated on the eastern banks of the Mississippi, Saint Paul is the “last city of the East”; west-bank-based Minneapolis is the “first city of the West.”

However, the Twin Cities are more than just these two cities. The Twin Cities region includes nearly 200 cities or townships across seven counties, and is governed by the Metropolitan Council. The Met Council, as it is so lovingly referred to, was set up in 1967 to plan for regional growth. Initially focused on sewer expansions, it has since encompassed transportation and parks systems as well. The world’s economies are no longer city-based, but region-based, so the systems that help them run should be planned accordingly. Before the Met Council, each of the two hundred small cities either ran their own agencies, or were coordinated by their respective counties (which, in turn, also functioned independently). Today, the Met Council assures that the plans of the individual entities of the region contribute to the collective vision: a region that is economically competitive on the national and world stages—where people of all walks of life want to come and live—and that is growing sustainably. All of those lofty goals won’t be achieved with the push of a single button. But intercity light rail transportation, at least, would finally get back on track.

THE SHORT TERM

The Green line opens on a gray day. Photo by Michelle Beaulieu.On June 14, 2014, the Green Line light rail line connecting downtown Minneapolis and downtown Saint Paul opened.On June 14, 2014, the Green Line light rail line connecting downtown Minneapolis and downtown Saint Paul opened.

On June 14, 2014, the Green Line light rail line connecting downtown Minneapolis and downtown Saint Paul opened.

There is a lot to this story, including the hard work of hundreds if not thousands of public employees, contracted firms, and politicians (not to mention a billion dollars, give or take) but that is for a history book for someone else to write. When it comes down to it, the project started in earnest in 2001. There were four years of planning, five years of environmental analysis, design and engineering, three years of construction and another year of testing before the first customers could ride the Green Line.

That process involved countless meetings with communities along the line. The Met Council worked to ensure that the people who tend to be underrepresented in community meetings were reached. The City worked with communities to create a vision for their neighborhoods that takes advantage of the transitway investment.

As a result, the City of Saint Paul has already seen a billion dollars in construction permits along the new Green Line. We’ve helped fund numerous affordable housing projects along the line, providing those in need with quality housing where they can have better access and commute more easily to their jobs. The City worked to get sidewalk and bicycle improvements constructed in conjunction with the project, connecting neighborhoods and creating those walkable urban neighborhoods. And this is how we are planning for our future populations.

These plans can take months or years to write, but once they pass and begin to be implemented, their impact can be felt almost immediately, depending on what you’re planning, what’s there now, who’s involved and how much they hate you, and (or) each other. But these plans typically take a long-term view, anywhere between ten to fifty years, and there’s the rub: they are the vision of the future. What kind of city do you want to live and work in, and how are we going to make that reality? What will change and what will remain?

These questions have thousands of answers. In Saint Paul, individual communities (seventeen in all) write their own district plans, which must conform to the City’s Comprehensive Plan, which in turn must meet the Met Council’s regional framework. Individual pieces of the plan may be influenced by various departments or agencies or layers of government, each of which has control over particular pieces of the urban environment. So, even as daily actions and decisions chart the course of a city’s future, it can take awhile to get there.

Along the way, city planners get yelled at a lot in public meetings. Politicians can get voted in and out of office, and they never seem to embody or envision the City in the same way as their predecessors, and we must adjust accordingly. We’re in the news, we’re on the radio, we’re expected to be professional experts who are impartial with every answer and no personal interest. We react to political shifts, and could have dramatically different bosses with opposing political views from one day to the next. (I feel this is an opportune moment to add that I work for the mayor of Saint Paul and it has been nothing but a joy since day one.)

And then, there is the stigma of being a public employee. We’re accused of being lazy (being a millennial gives me that reputation twofold), and we’re accused of not caring about the community, or businesses, or fiscal responsibility, when the reality could not be further from the truth.

Strong stomach, thick skin, boundless optimism.

Saint Paul Downtown Airport in Saint Paul, Minnesota. The Mississippi River wraps around it. Downtown Saint Paul is visible to the upper right of the airport. Photo by Bobak Ha’Eri, Wikimedia Commons.

YOU HAVE TO CARE

The environment around us shapes our daily life. That’s why I became a planner. Think about how you chose your apartment or your house, whether you chose to rent or to buy. Think about how you get to work and where you go to lunch, how safe you feel in your downtown at night and where you like to go jogging. Planning shapes people’s lives without us even knowing it.

Planners (and engineers, and elected officials) are professionally charged with these issues, addressing them with case studies and examples from other cities that may have something we think we’re lacking. External consulting teams also play a part, carrying out studies and providing data to back up various recommendations. But these are cities where people live their lives, and so the job cannot be complete without listening to what the community believes is best for its city.

The world’s urban population is expected to double by the middle of the 21st century. The Twin Cities region alone is projected to grow by 800,000 people, while adding over 500,000 jobs by 2040. Figuring out where and how these people will live and accounting for the future is not a trivial problem. In fact, it’s possibly the most pressing problem of our generation.

And to the millennials: We know that our generation wants cities with those walkable, urban neighborhoods. We are the largest generation in the country right now. And yet, based on most of my public meetings, you would never know. If history is written by the victors, then city planning decisions are made by those who show up. I have a sneaking suspicion that you, dear reader, probably are not the elderly woman who came to my meeting last week, upset that an apartment building is going up four blocks away from her and convinced it’ll change her neighborhood.

So if you’re not paying attention to your city, you should be. Listen to your local elected and unelected officials. Check out your local community planning meetings. And if you are already going to those meetings and want to talk about it, let’s get coffee sometime.

Michelle Beaulieu is a City Planner with Saint Paul’s Department of Planning and Economic Development. She works primarily on transportation and neighborhood planning projects. She also serves on the boards of directors for her neighborhood association, CARAG, and for St. Paul Smart Trip, the Saint Paul transportation management organization. Previously, Michelle worked in bicycle and transit advocacy in Minneapolis, assisted for architecture and design courses in Copenhagen, Denmark, and held urban planning and design internships in New York City and Providence, Rhode Island.

Michelle Beaulieu is a City Planner with Saint Paul’s Department of Planning and Economic Development. She works primarily on transportation and neighborhood planning projects. She also serves on the boards of directors for her neighborhood association, CARAG, and for St. Paul Smart Trip, the Saint Paul transportation management organization. Previously, Michelle worked in bicycle and transit advocacy in Minneapolis, assisted for architecture and design courses in Copenhagen, Denmark, and held urban planning and design internships in New York City and Providence, Rhode Island.